IMPACT

European regulators poised to reveal limited implant safety data

Tens of thousands of confidential accident reports have been kept from doctors and patients every year, but some may get released.

Hidden evidence on the safety of medical implants, buried in tens of thousands of confidential accident reports submitted to European regulators each year, could be summarized and made public for the first time from next year.

The European Commission has told the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists it is in detailed discussions with member states about publishing at least some information from accident records, known as “serious incident reports.”

Although the amount of accident data summarized annually for each implant is likely to fall short of the level of detail demanded by leading doctors and public health groups, the commission is hoping to ensure meaningful disclosures for the first time.

“The extent to which incident reports … are to be accessible to the public is still under discussion with the [regulators] from member states,” a commission spokesperson told ICIJ. “The primary concern is protecting patients’ health and their right to transparent, complete and correct information.”

In the United States, implant manufacturers and hospitals are required to submit accident reports to the Food and Drug Administration, and the regulator then posts all of them on a publicly-accessible online database called the Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience, or MAUDE.

In Europe, officials are working on new transparency requirements for EU accident data, but they remain under pressure from manufacturers to keep large numbers of reports confidential. In particular, the commission may decide not to publish information contained in accident reports in which investigators only suspect a medical device may have caused a patient serious harm – but have been unable to conclusively find that was the case.

The commission spokesperson told ICIJ that it would only release records where there was evidence of “actual systemic risk” of device failure, so as to “avoid unjustified mistrust and concerns.”

This means doctors and patients are likely to have only limited access to the accident data held by regulators. Far less safety data would be accessible to the public in Europe than in the U.S.

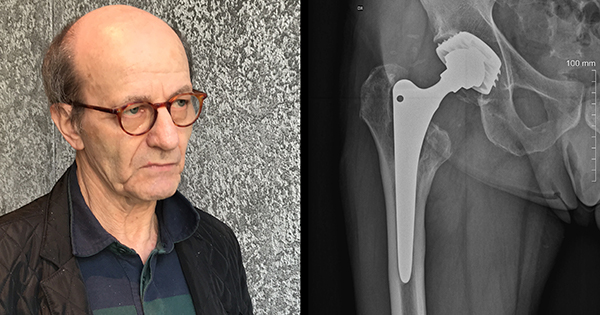

The commission’s efforts to improve data transparency come six months after ICIJ’s Implant Files investigation highlighted multiple examples of dangerous implants that were approved as safe for use in the European Union but went on to cause unexpected and serious harm to thousands of patients. Journalists found that calls for stricter safety rules and greater transparency were resisted by powerful implant manufacturing trade groups, led by MedTech Europe.

Reporting by ICIJ and its partners also revealed how the number of confidential incident reports submitted to regulators across Europe had risen steeply, tripling in less than 10 years in many countries.

The safety of a new implant is often harder to assess than the safety of a new drug because it can take years before significant numbers of patients develop problems with the devices implanted in their bodies.

As a result, regulators can only gain a full understanding of the safety of implants after a period of many years in which suspected device malfunctions are recorded and analyzed.

EU patients will still have less safety information than those in the U.S.

For the last 26 years, European regulators have been barred from disclosing safety data from incident reports because, under EU rules, this information is deemed commercially confidential.

Updated medical devices regulations were passed into law in 2017 and are due to come into effect next year. The new legislation does not commit EU regulators to full transparency but states that the public should be “adequately informed.” It does not say how this should be achieved and does not stipulate how much data on suspected product malfunctions should be published.

Meanwhile, in the U.S., Scott Gottlieb, before stepping down as FDA Commissioner in April, promised his agency would further increase data transparency after reports by ICIJ and others showed there were gaps in the MAUDE database.

“[I]t’s imperative that all safety information be made available to the public,” Gottlieb said in March. “We’re now prioritizing making ALL of this data available.”

Last month, the FDA made good on this promise, releasing more than 6 million incident reports since 1999 that had failed to show up on the public MAUDE database.

Medical device industry’s aggressive lobbying

Back in Europe, ongoing deliberations about data transparency are taking place behind closed doors within a working group set up by the commission. The group includes national regulators as well as representatives from 28 organizations, who sit in on talks as “observers.”

Although EU rules require observers on all working groups to be listed online, in this case the commission failed to make the names public until it received an information request from ICIJ.

Of the 28 observer organizations on the working group, 20 are trade bodies or other commercial interests. They include MedTech Europe.

MedTech Europe has led aggressive lobbying efforts on implant regulation for over a decade. In 2008, the trade body wrote to the commission saying it was “concerned” at the prospect of radical reform, insisting there was “no evidence” Europe’s light-touch system was any less safe than regulation elsewhere in the world.

‘We shouldn’t be afraid of transparency’

In 2015, MedTech Europe held a private meeting with EU officials about data transparency, according to an internal commission memo, released to Le Monde newspaper, an ICIJ media partner, in response to a freedom of information request.

The memo described how, during the meeting, the lobbyists issued a dark warning. They explained that if new European regulations struck the wrong balance between data transparency and commercial confidentiality the EU may no longer be considered “fit for attracting innovation and research investments.”

After the Implant Files investigation was published, ICIJ and MedTech Europe were both invited to give presentations to the European Parliament in February. Despite MedTech’s previous concerns about data transparency, chief executive Serge Bernasconi claimed to be in support of greater openness.

He told members of the European Parliament: “We have to be transparent. We shouldn’t be afraid of being transparent. Anyway, that’s what’s happening already in other places around the world. So I don’t think that we have anything to hide.”

MedTech Europe’s apparent new-found support for data transparency took some MEPs by surprise. The parliamentary committee chair Adina-Ioana Vălean welcomed his comments and said: “We will keep the industry at your word that much-needed transparency and public knowledge is going to be there, in the interests of everyone.”