On the evening of April 28, 2010, in an emergency room in the Georgia mountains north of Atlanta, police handcuffed a 60-year-old woman named Bonnie Magar. She had come to the clinic seeking help for a set of mysterious ailments that included recurring hallucinations, psychotic episodes, and flu-like physical symptoms.

It was at least her sixth visit to the hospital in the small town of Hiawassee. The previous month, Magar had arrived at the clinic begging for relief from an array of torments including migraines and “visions of seeing her dead body on the side of the road … as well as the smell of burning flesh and metal,” according to hospital records.

Magar’s attending doctor initially determined that she was experiencing altered perception stemming from a type of epileptic seizure. Except she didn’t have epilepsy. According to Magar, several hours passed, and the doctor came to a different conclusion: She was a junkie suffering from opioid withdrawal.

That evening, the doctor deemed Magar a suicide risk and called the police to transport her to a drug rehab center.

Magar, a quick-witted former nurse who had traded her Southern Baptist upbringing for Sundays of meditation, didn’t abuse opiates. But two years later, she would come to agree with the ER doctor: The symptoms tormenting her were a byproduct of drug dependency. To blame, she and her current physician believe, was an implanted pain-management device that was malfunctioning, delivering too much or too little morphine into her spinal column, inducing mind-bending cycles of overdose and withdrawal.

“For years, I’d been so desperate to figure out what was wrong with me,” Magar said, gesturing to her abdomen. “And it was the pump all along.”

The device, the SynchroMed II pain pump, was manufactured by Medtronic PLC. It was implanted in more than 250,000 people before U.S. authorities in 2015 asked a court to largely halt its sales after patients around the world reported overdose and withdrawal symptoms similar to Magar’s. In a statement to the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, Medtronic characterized the device’s problems an exception to its high standards and said that, after working with regulators to fix the issues, the company continues to sell the SynchroMed pump.

But Magar’s model of pump is one of a wide variety of implanted medical devices that have seen trouble only after being implanted in massive numbers of patients worldwide — including faulty hip replacements, controversial pelvic meshes and substandard heart devices.

When Magar’s pump was deactivated, her symptoms vanished.

But what about the implant itself? Unable to afford the surgical procedure required to remove it — known as an “explant” — Magar was left with the inert device inside her body. Her troubles were just getting started.

Miraculous success stories and avoidable failures

Rapid innovations in science and technology have led to a booming worldwide market for high-tech implantable devices. The industry’s stellar growth is due in large part to popular demand for the products, and device makers have millions of success stories to celebrate across the globe. Pacemakers save lives of people with irregular heartbeats. Lens implants give sight back to those struggling with cataracts. Artificial knees allow the disabled to walk again. The type of pump installed inside Magar, for its part, holds the genuine promise to treat severe chronic pain and other ailments with microdoses of drugs delivered directly to the spine.

But regulators often don’t require large-scale human trials for devices like they do for prescription drugs. As a result, authorities have allowed faulty devices to come onto the market, where they have lingered for years even as injuries mount, a global examination by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists found.

In hundreds of interviews with ICIJ and its partners as part of their global investigation known as the Implant Files, patients living with implants subject to safety concerns expressed frustration over a chaotic and often non-functioning global system of delivering vital information regarding the devices. More than 200 patients said that doctors did not warn them of the risks of their implants or did not inform them of relevant recalls or safety alerts.

These removal procedures are unbelievable, horrifying experiences – Hanifa Koya

If a drug goes wrong, patients can stop taking it. Many implanted devices are installed adjacent to vital organs or pressed against sensitive nerves, meaning removal may carry risks of serious injury or death. The potential dangers of removal often outweigh the benefits of continuing to live with a problematic device, leaving patients to choose which gamble to take. By their nature, implants are particularly hard to examine, and many patients, like Magar, often don’t realize that their implanted device is broken or defective — or at an elevated risk of malfunctioning.

As part of its year-long investigation, ICIJ created a machine learning algorithm to comb through the text of millions of malfunction, injury and death reports filed by manufacturers and others to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Nearly 500,000 reports over the last decade describe explant surgeries in connection with a medical device.

These reports are known to capture only a fraction of total events tied to device problems and they don’t always make clear whether an explant was a direct result of a malfunctioning device. Nevertheless, they provide a window into massive waves of removal surgeries that have occurred amid recalls or market withdrawals.

The SynchroMed II pain pump, Magar’s device, is linked to nearly 14,000 explant surgeries since 2008, the analysis found.

The data also includes descriptions of nearly 8,500 women who had Essure, a controversial permanent contraceptive device, surgically removed from their fallopian tubes — and the removal of more than 12,000 implanted defibrillators made by St. Jude Medical in the wake of a massive 2016 recall.

Beyond the numbers, ICIJ interviews with dozens of patients who had medical implants removed bring into sharp relief the often grisly toll of explant surgery: femur bones snapped during removal of recalled hip implants, massive blood loss during the retrieval of a faulty heart device, dangerous synthetic materials abandoned inside the spine.

“These removal procedures are unbelievable, horrifying experiences,” Hanifa Koya, a gynecologist at Wakefield Hospital in Wellington, New Zealand, said of her work explanting dozens of controversial vaginal mesh devices linked to severe complications before the country temporarily banned certain types of the meshes late last year.

Even apart from these worst-case scenarios, millions worldwide live with devices inside them that have been recalled or voluntarily withdrawn from the market amid safety concerns and now contend with the uncertainty of whether or when their device will malfunction.

Most recalls aren’t cause for alarm, as many identify problems that pose no grave danger to patients. Some can be easily remedied with a software update or some other fix. Even in the highest-profile cases, many patients with devices subject to recalls don’t experience complications.

Medtronic did not respond to a question about the thousands of reports describing SynchroMed removals, but pointed to an FDA disclaimer stating that conclusions about a device’s safety or role in an injury or death cannot be made from an adverse event report alone.

Justin Paquette, a spokesperson for Abbott, which now owns St. Jude Medical, said that neither the company nor regulators recommended that its recalled defibrillators be explanted and replaced, but “some physicians managing patients with unique clinical considerations” made that decision. Paquette said that, in those instances, the company provided replacement devices and reimbursed some medical expenses.

In response to questions over the thousands of Essure removals, a spokesperson for Bayer noted that such reports can be filed by anyone and that many were submitted by people suing the company. “The FDA states that these anecdotal reports have a number of significant limitations.”

Patients living outside a manufacturer’s home jurisdiction face steep challenges in getting compensation for, or even information about, defective devices. These patients can find one dead end after another, from courts that afford limited rights to foreign claimants, to sky-high legal costs, to manufacturers simply rejecting or ignoring claims from patients abroad.

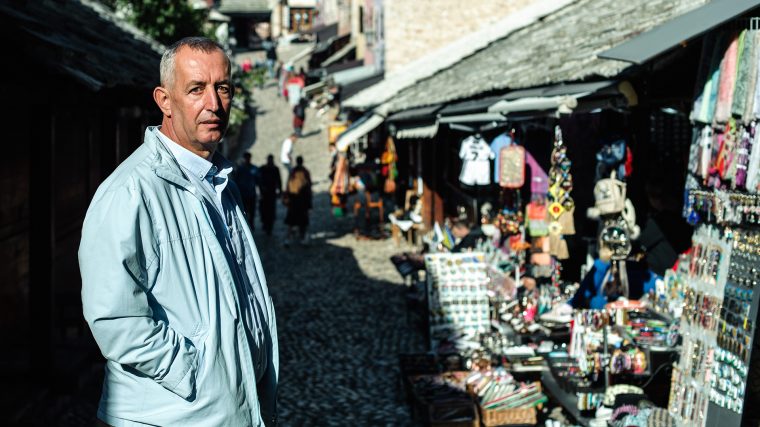

Among those struggling is Sang-Ho Jeong, of Seoul, South Korea, who is waging an uphill fight as a foreign plaintiff in a lawsuit in U.S. federal court against a maker of recalled hip devices. In South Africa, women injured by controversial mesh implants told ICIJ of a shortage of both doctors willing to remove them and lawyers willing to take their cases. In Mostar, Bosnia, a retired cab driver named Hadis Brajevic lives with a deactivated defibrillator in his chest and is fighting to compel the device’s German manufacturer to pay compensation for medical bills and suffering.

“It’s hard to live with the device,” Brajevic said. “But the hardest part is thinking about dying with it.”

In the opioid crisis, an opportunity

In the late 1990s, with assurances from drug manufacturers that the American public would not become hooked on opiates, doctors began prescribing the painkillers at accelerating rates, creating a crisis that continues to grip communities across the country. As the opioid epidemic metastasized, the medical device industry was already developing a potential solution: implanted pain pumps meant to carefully regulate tiny doses of liquid drugs.

In 1988, the FDA approved the first SynchroMed implantable pump via the agency’s most rigorous pathway. Known as a Premarket Approval, or PMA, this route often requires less robust clinical data than approvals for drugs.

SynchroMed’s approval followed tests in 14 dogs and 160 people. The study tracked only 27 of the humans for more than a year.

Drug approvals typically require multiple trials that involve thousands of human subjects and often stretch for years.

AdvaMed, the U.S.’s leading medical device industry association, said devices — which are more difficult to randomize in clinical trials — should not be compared to drugs and that requiring large clinical trials is not appropriate for devices.

The FDA stands behind its 1988 approval standards for SynchroMed. Addressing its trial length, the FDA said the original SynchroMed approval was largely meant to clear the device for people with terminal conditions who would not need the pump for very long.

In the years that followed the 1988 approval, Medtronic vastly expanded the device’s user base by including drugs that appeal to chronic pain patients with decades of life ahead of them. This happened through a route intended for changes to an already approved device, known as a PMA supplement.

This approach is a routine way for companies to incrementally alter devices and their uses. Supplements can require no clinical data whatsoever. Still, the changes can be hugely consequential. In 2016, the U.S. Congressional Research Service released a report critical of this approval route, pointing out that two of the most catastrophic recalls of heart devices — involving nearly 500,000 faulty pacemaker wires implanted in the hearts of patients worldwide — were cleared via PMA supplements without any prior human trials.

In 2003, Medtronic used this same pathway to approve its new generation pump, the SynchroMed II. Hailed by Medtronic as an “incredible advance in medical technology,” the new pump was smaller than the older version but could hold more drugs.

As a condition of its approval, the FDA required Medtronic to perform a study on the new pump after it hit the open market. The study included 80 patients. The agency would later conclude, in assessing the study’s weaknesses, that it did not capture over- and under-dosing of drugs as potential problems, and noted that “the data may not be clinically meaningful.”

In comments to ICIJ, the FDA defended Medtronic’s use of the supplemental pathway and the integrity of its post-approval study. The agency said it only doubted the quality of information captured outside the study’s essential parameters. The agency also deleted the line questioning the data’s meaningfulness from its online description of the SynchroMed II study.

(The day after the FDA informed ICIJ of this edit to its website, the agency issued a detailed safety alert warning of risks of common but unapproved drugs used in implantable pain pumps — a device market that SynchroMed pioneered.)

In August, 2006, FDA inspectors made the first of many troubling findings at the Minneapolis headquarters of Medtronic’s neurological device division. In one of several warning letters to the company, inspectors faulted Medtronic for its failure to properly manufacture the pump, fix a spinal catheter with quality issues and respond appropriately to customer complaints.

More than a decade later, it remains unclear to what extent the problems with SynchroMed pumps had to do with the device’s fundamental design or to manufacturing errors that led to deviations from that design.

Whatever the ultimate cause, in 2006, health regulators began to realize they had a problem.

At the start of the journey — a traffic wreck

Bonnie’s Magar’s odyssey with her SynchroMed implant began with a car accident. On Oct. 23, 2000, a decade before her visit to the Hiawassee emergency room, she was driving to work through the rural outskirts of Hillsborough, North Carolina, where she lived at the time, when she rear-ended a utility truck and shattered every bone in her left wrist.

The initial numbness of shock yielded to a drilling, maddening pain, like nothing she’d felt before. And it wouldn’t go away. Weeks passed, then months, but each day brought pain rivalling what she felt in the immediate aftermath of the wreck.

The crash had triggered a condition known as complex regional pain syndrome, which causes a person’s brain to register excruciating pain long after an injury has healed.

Local doctors told Magar she could either cope with the torment or take tranquilizing doses of oral opiates.

In 2002, faced with two bad choices, Magar went to see Richard Rauck, a renown pain doctor who practiced in Winston-Salem, some 70 miles from her home. With a corpus of published research and a sizable staff, Rauck carried an air of prominence and authority that felt different from her previous doctors, Magar said.

Rauck recommended SynchroMed. The pump, a silvery disk the size of a hockey puck, was placed just under Magar’s skin on the right side of her abdomen. A synthetic tube snaked from the pump through a pair of vertebrae and into her spinal column, where it was meant to deliver liquid drugs in precise doses without the sedating effects of opiate pills.

The device gave Magar immediate relief that allowed her to resume her regular life, seeing friends and pet-sitting.

But in 2006, she started to experience occasional symptoms she struggled to explain. She remembers the first episode clearly: Standing in her kitchen, she smelled something burning. The odor became so overpowering that she felt she could taste it. Magar feared her home was on fire. “So I called 911, and these big, burly men stomped through my house,” Magar recalled. “But they couldn’t smell anything.” Before leaving, the firefighters suggested Magar might be having a panic attack.

Nothing was ablaze. Instead, Magar was hallucinating tastes and smells. She didn’t know it, but she wasn’t alone. More than 700 people reported the same strange sensations to the FDA as suspected side effects of SynchroMed implants believed to be malfunctioning, according to public records.

Around 2008, doctors replaced Magar’s older SynchroMed pump, which was on the verge of expiring, with the SynchroMed II. She says this marked a dramatic intensification of her symptoms.

In the years that followed, Magar’s life degenerated. Often, the phantom odor was followed by an unconquerable exhaustion that left her bedridden for days, pushing her out of work and into seclusion. “I could force myself to get up to use the bathroom and to dump food out for my cats,” Magar recalls, “I mean, I would literally just dump it onto the floor. It was a mess.”

When the sleeping spells would end, she would suddenly find herself all too awake — wired — and beset by a sort of cosmic anxiety and insomnia that could last another several days. Her fraught mental state would arrive with severe flu-like symptoms: severe headache, sweating and constant sneezing, Magar said.

In 2010, shortly before the emergency room visit and psychiatric hospitalization in Hiawassee, where she had moved several years prior, Magar flew to Oregon to visit her ex-husband and close friend, Nazih Magar, who was losing a long fight with cancer. She tried to console him, but she was not well herself, Magar recalls. “He said, ‘You look worse than me, and I’m dying.’”

The global fight for redress and removals

Like Magar, many patients interviewed by ICIJ and its partners said that, upon implantation, they had assumed there would be some strategy for removing a device if it malfunctioned or was recalled. They expected an exit plan.

Hadis Brajevic, the retired Bosnian cab driver, said that even being wounded by shrapnel from Serbian tank fire in his hometown of Mostar didn’t prepare him for the trauma of living with a defective defibrillator in his chest. Implanted in 2012, the device began delivering terrifying storms of electric shocks to his heart shortly before he had it turned off in January 2016, Brajevic said.

Despite the life-saving nature of ICDs, shocks, both appropriate and inappropriate, present a very definite burden to the patient – Biotronik

Today, Brajevic is waging a shoestring fight against Biotronik, the pacemaker’s Berlin-based manufacturer. He says his strategy consists largely of writing letters to European regulators and company representatives asking for compensation for medical bills and suffering.

Biotronik has refused to budge, blaming the device’s problems on what it calls “external causes” such as “different anatomic conditions or implant locations,” according to an email a Biotronik attorney sent Brajevic earlier this year.

Suing Biotronik in German court is not an option for Brajevic. “The [government pension] money I receive is $400 a month,” Brajevic told ICIJ. “And the lawyer in Germany — he requires at least $500 or more per hour.”

In response to ICIJ’s questions, Biotronik said it could not comment on specific patients but defended the safety of the heart device inside Brajevic. The company also addressed a range of complications common with the devices, often referred to as ICDs.

“Despite the life-saving nature of ICDs, shocks, both appropriate and inappropriate, present a very definite burden to the patient,” Zara Barlas, a spokesperson for Biotronik, said in response to questions about Brejavic’s case.

Even patients living in affluent countries can struggle for equal treatment across borders. A group of patients in South Korea has for years been fighting for compensation for flawed metal-on-metal hip implants made by Johnson & Johnson.

Jeong Sang-Ho is one of these patients. Jeong, a 47-year-old a former clerk at a waste management company in Seoul, said that a malfunctioning Johnson & Johnson hip he received in July, 2008, left him temporarily disabled and jobless after the device disintegrated inside his body.

Jeong describes learning to his horror that the metal of the artificial hip had badly degraded his leg’s bone structure to the point that the artificial joint itself dislocated, wreaking havoc inside other joints in his right leg. “The device was piercing into my thigh, which caused me to bleed a lot, and it felt like there were a thousand needles poking into my leg,” he said.

Even worse, a second artificial hip implanted in August 2010 to replace the flawed implant was itself recalled just weeks after the operation, although Jeong asserts he was not notified of the recall until 2013.

In response to questions regarding Jeong’s case, Johnson & Johnson touted a compensation program it created for those who received Jeong’s variety of hip, known as the ASR. “The company has voluntarily compensated ASR patients by taking the unprecedented step of addressing the costs of recall-related medical care and associated out-of-pocket expenses and lost wages through the ASR Reimbursement Program,” said Ernie Knewitz, a spokesperson for Johnson & Johnson. “The program is available to all patients globally, and participating in the program does not require patients to waive their legal rights to pursue a claim against the company.”

Like Brajevic, Jeong said a large part of his daily life is taken up by the fight for justice over his faulty implants. So far, he said, he has received the equivalent of approximately $600 in compensation. Meanwhile, in 2016, a federal jury in Dallas ordered that Johnson & Johnson pay $1 billion to several Americans injured by a different type of metal-on-metal hip replacement made by Johnson & Johnson. The company is appealing the ruling.

“This has affected my health, and it’s in my body still,” Jeong said. “I am very sad that I did not get the same benefits as Americans did.”

A desperate search for answers

Magar suspected for a while that the pain pump might be to blame for her symptoms. But when she traveled to her doctor Richard Rauck’s office for morphine and clonidine refills, delivered via a syringe through her skin and into the pump, she was told the device was dispensing the drugs in tiny amounts as intended, Magar said. Rauck’s staff told her the problem lay elsewhere, she claims.

So Magar traveled to specialty clinics across the South in search of answers.

Rauck declined ICIJ’s request for an interview. Rauck provided a brief response to a detailed list of questions and said that he did not recall some events as Magar had described. “I remember Bonnie well, although it has been over five years since I have seen her,” he said in an email. “I remember that she certainly had a difficult and complex pain problem. We worked hard to try and help her manage her symptoms for several years.”

As an array of doctors speculated on causes of Magar’s problems ranging from hormonal imbalances to mysterious neurological disorders, her family began to suspect that she had simply gone mad.

“We had no idea what was happening to her,” her daughter, Tonya, recalled. “We would brainstorm and would have her go see every ‘ologist’ you could name.” This included kidney doctors, hormone experts, a gynecologist and allergists.

Tom Gary, a north Georgia physician whom Magar began visiting a few months after her emergency room apprehension by police, was also stumped. Despite seeing Magar eight times during the final four months of 2010, Gary said he made little progress finding a diagnosis for her extreme spells. “I had no clue where to go with her,” Gary recalled.

One day in late 2011, at a bowling alley in Hiawassee, an acquaintance insisted to Magar that her symptoms were the tell-tale signs of overdose and withdrawal.

That night, Magar returned home and searched the web for symptoms of opiate abuse. On one site, she saw that 20 of 21 symptoms matched perfectly. “I sat there staring at my computer and just cried,” Magar said. “I said: ‘This is it.’”

Furious, Magar demanded an in-person meeting with Rauck, who had since grown to national prominence with his own pain magazine and a practice that treated more than 10,000 patients a year.

Records detailing Magar’s visits to Rauck’s office show his physicians taking Magar’s complaints seriously and speculating on a number of root causes outside the pump itself, including other prescription drugs she was taking and various physical factors. In the records ICIJ reviewed, Rauck’s doctors do not address the possibility of a pump malfunction. Some records show Magar complaining of dizziness, a symptom she believes was not related to any pump malfunction. Beginning in 2009, the clinic began gradually lowering Magar’s doses of drugs, partially in response to her complaints of fatigue.

In June, 2012, Rauck met with Magar and agreed to turn off the pump. But removing it was another question altogether. “She does not have any insurance and has been told by the hospital it is a $10,000 procedure to have it removed,” Rauck noted in Magar’s medical records, adding that he would try to help her through the ordeal. Magar says Rauck offered to cut in half his own fees related to the removal, separate from the hospital expenses, but she still couldn’t afford the overall price.

“So I just cried some more, because I don’t have that kind of money,” Magar said. “So I told him: ‘I guess it will just stay in me.’”

In the weeks after the pump’s deactivation, Magar felt what seemed an entirely novel emotion: joy. The opiate withdrawal symptoms vanished, and her attacks stopped. Magar resumed her life, rebuilding friendships, seeing more of her two grown daughters and attending bowling nights at her local alley.

“I was free,” she said. Curiously, the pain associated with her once-chronic pain had disappeared as well.

Yet her ordeal with the pump wasn’t over. The prior year, Medtronic had completed a recall of more 100,000 SynchroMmed II pumps bearing the same model number as hers. Classified as the most serious type of recall, the action didn’t remove the pump from the market but urged doctors to heed a letter from Medtronic warning of reports that the pump’s catheter could cause an “inflammatory mass formation” in patients’ spines — a condition that can cause not only back pain but also severe injuries and permanent disability.

Not long after her pump was deactivated, a pain in lower spine began to steadily grow more severe. By Christmas of 2017, the agony had become constant. “Standing in line was almost impossible,” Magar said. “If I tried to sit up straight for any length of time, it would cause a great deal of pain.”

Chaotic global recall system

It can be hard to know when to have an implanted device removed.

Recent history suggests that being too quick to have an explant can have deadly consequences. Several physicians who work with implanted devices pointed to a botched effort decades ago to correct problems with the Telectronics Accufix, a brand of wires that connect pacemakers to human hearts. In November 1994, its manufacturer initiated a recall of 36,500 sets of wires prone to fracturing.

The announcement led to thousands of patients having their chests cut open to remove the recalled wires.

But research published years later showed that the explant surgery itself caused more than a dozen deaths — a significantly higher mortality rate than for those who opted to retain the recalled devices.

How a recall is worded and how well it is communicated is critically important to whether patients even have a chance to make an informed decision about whether to explant a defective device.

In the critical period after an implant has been found to be defective, device companies must scramble to analyze preliminary data to come up with a proper risk/benefit analysis, said Leslie Saxon, a professor of medicine and cardiac electrophysiologist at the University of Southern California. Saxon has worked with both patients and device companies to navigate large recalls, including a massive recall earlier this year of more than 700,000 heart devices, made by St. Jude Medical, that had software vulnerable to cyber attack.

“It’s super hard,” Saxon said, “I’ve had patients say, ‘I want this device out,’” Saxon recalls, noting that such instances have been rare. “If I didn’t feel good about taking it out, based on what I knew, I’d say, ‘Look, I don’t agree with you.’ I’d refer them to someone else.”

Saxon added that device recalls are often worded by companies, frequently in coordination with regulators, to leave room for discretion at the clinical level. “At most institutions, there are like five to 10 of me who all get together and we say, ‘OK, what are we going to do?’” Saxon said.

Recall notices are broadly worded partly because individual patients’ interaction with devices can vary widely and partly because, in the early phase of a recall, companies rarely have a full picture of the problem and want to protect against the sort of overreaction seen with the Telectronics Accufix wires. Such wording can benefit patients with attentive doctors willing to explain the situation and discuss a way forward that fills each patient’s needs. For others, it can leave years of lingering doubt.

Matt Hooks, an engineer living in South Lanarkshire, Scotland, said that his physicians seemed to only vaguely understand details of a serious recall on his pacemaker in 2016. “I had to harass the clinic to be seen,” Hooks recalls. “There was no flow of information from them to me.” Two years after the urgent safety warning, Hooks’ heart is still fully reliant on the recalled pacemaker. The device is working properly and the recall does not recommend explantation, but he says he wanted a meaningful consultation with his doctors. “I was never called on to discuss that decision,” he said.

There’s so much that can go wrong. It’s really, really scary – Matt Hooks

Hooks is one of more than 200 patients interviewed by ICIJ and its reporting partners who complained they were not provided sufficient safety information about their implants. Most countries, including the U.S., don’t have a central registry of patients with implants or other ways to easily track devices, causing device companies and hospitals scramble to locate patients in the wake of a large recall. Each recall is different, and many require only doctors to be notified of a problem. Experts say it can often be easier to track tainted meat or faulty car parts than to find a patient with a recalled implant. Hooks, for instance, learned of the recall on his pacemaker from a friend.

ICIJ’s interviews revealed another common problem: Devices are sometimes recalled or subject to safety alerts in some countries but not others.

Connie Hill, a 72-year-old resident of Sun City, Arizona, is one of several patients who say they wished they had known earlier of foreign safety alerts on a metal-on-metal hip implant manufactured by Biomet alleged to cause an array of disabling complications. “I never heard a damn thing about it,” Hill told ICIJ.

In 2015, the company issued a safety alert for people implanted with the device in Australia and published subsequent alerts in the United Kingdom, Ireland, Denmark, Germany and Italy. But Biomet has not conducted any similar action notifying doctors or patients in the U.S. or Canada of the problems.

Late last year, Hill’s doctor noticed significant bone loss around the Biomet device, Hill said. Blood tests revealed greatly elevated cobalt and chromium. The device would have to be explanted.

In comments to ICIJ, the company, now called Zimmer Biomet, did not respond directly to questions regarding its uneven application of safety alerts around the world but defended itself in broad strokes. “We adhere to strict regulatory standards,” the company said in a statement, “and work closely with the FDA and all applicable regulatory agencies in each of our regions as part of our commitment to operating a first-rate quality management system across our global manufacturing network.”

In a statement to ICIJ, the FDA pointed to a generalized safety communication it had posted online in 2011 about metal-on-metal hips as a reason for not requiring a recall of the Biomet hip.

Shortly before her explant surgery this past September, Hill told ICIJ that her doctor had warned her of a series of potential nightmare complications of removal, including paralysis and death. Fortunately, none of these complications emerged during her surgery.

“There’s so much that can go wrong,” Hill said. “It’s really, really scary.”

Legal and Surgical Interventions

Just before dawn on a Wednesday last April, Magar swayed in the backseat of her Kia SUV as her daughter navigated switchbacks leading from her Appalachian home to an operating room near Atlanta. During the 90-minute drive, Magar hunched forward, her hands crossed in her lap to stabilize herself along the winding road. If she sat up straight, the defunct pain pump would deliver the familiar jolt of agony.

But, if all went well, the pump would be out of her body that afternoon.

Weeks prior, a doctor in Gainesville, Georgia, had identified the removal of the pump as medically necessary to fix her back pain. The catheter had caused a dangerous mass to form within Magar’s spine, and it had to come out. Magar was now covered by Medicare, and the operation’s cost was no longer an issue.

Between 2006 and 2012, FDA inspectors repeatedly faulted Medtronic for not properly addressing complaints of inflammatory masses in the spine, which the agency called “reportable as serious injuries” and said could lead to “partial paralysis, total lower limb paralysis.”

In 2013, FDA investigators found more problems with SynchroMed manufacturing and Medtronic’s quality control processes. In 2015, after nearly a decade of seemingly fruitless warnings to the company regarding safety issues with the pumps, the FDA enlisted the Justice Department to bring Medtronic under a consent decree, largely forcing the company to stop making and selling the troubled pumps until it had fixed the problems.

In September, 2017, the FDA lifted its sales restrictions on the device. Earlier this year, the FDA approved a new version of SynchroMed II that Medtronic said represented “a major milestone under the consent decree.” The latest version of the SynchroMed II generates performance reports patients can read on a tablet.

In a comment to ICIJ, Medtronic touted its progress under the consent decree. “Medtronic worked with the FDA to correct these issues and to implement procedures and processes to prevent such situations from occurring in the future,” Medtronic said. “It is important to note that Medtronic continues to produce and market the SynchroMed infusion system today with all required regulatory approvals, delivering safe, effective and life-enhancing therapy to patients around the world.”

But the story isn’t over for some living with the older pumps. During the final year of the consent decree’s full restrictions — even as sales of the pump remained tightly controlled — thousands of adverse event reports were submitted to the FDA for the SynchroMed II, describing a range of symptoms suspected linked to the devices including overdoses, withdrawals and injuries.

For Magar, though, her 15-year ordeal was finally ending.

At around 10 a.m., Magar’s name was called, and a nurse led her behind a pair of large swinging doors.

Three months later, Magar was visiting with her daughter in the second-floor apartment on the outskirts of Blairsville, Georgia, where she moved last year. She looked more lively than before her surgery, perhaps partly because was standing up straight. The device had been successfully removed, including the spinal tubing, which came out in several pieces, doctors had told her. Her back pain was gone, she said. When the bowling season began again the following month, she would be there — pain free.

When asked how she felt, she responded simply, “I’m just so glad it’s finally out.”

Contributors to this story included Emilia Díaz-Struck, Rigoberto Carvajal, Cécile S. Gallego, Boyoung Lim and Razzan Nakhlawi.