As part of ICIJ’s Implant Files investigation, we looked at a new type of heart valve, called TAVR (or TAVI, depending on where you’re from), and how manufacturers like Edwards and Medtronic are manufacturers are finding creative ways to market directly to patients.

Here are five takeaways from our investigation.

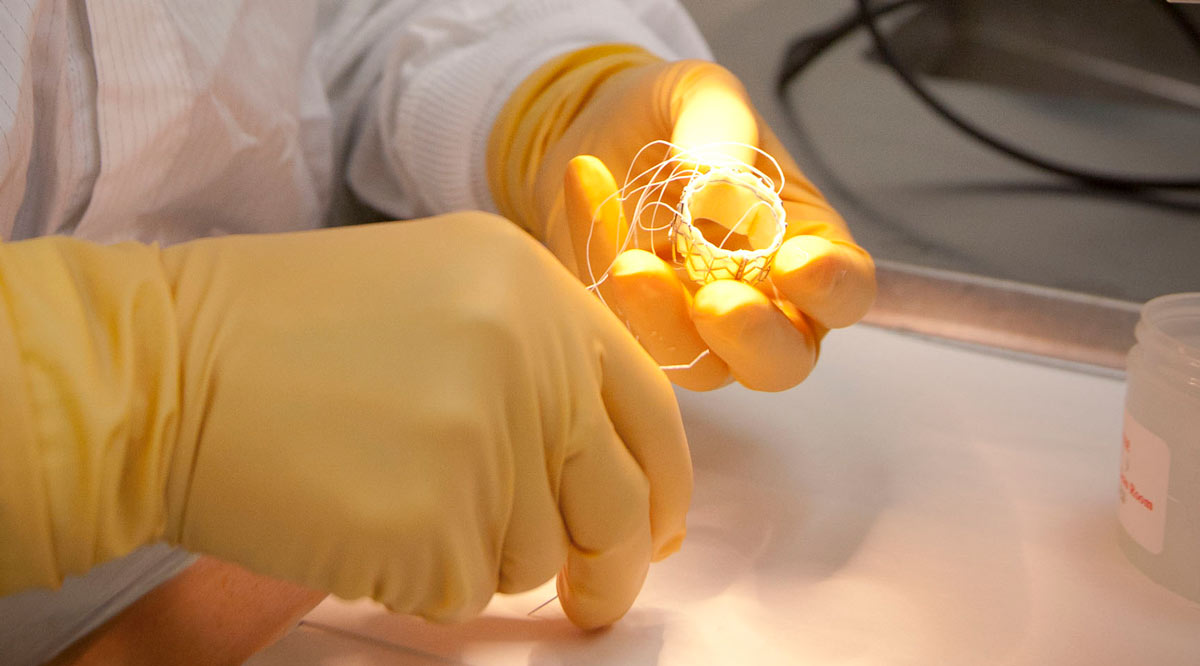

TAVR is a heart valve replacement that can be implanted without open heart surgery

Aortic stenosis is a common disease where one of the heart valves narrows, restricting the flow of blood into the body. When it gets bad enough, the diseased valve often needs to be replaced. For decades, the only option was open-heart surgery to cut out the damaged valve and sew in a new one.

The newer alternative is far less invasive. Cardiologists compress an artificial valve into a tiny package on the end of a thin, flexible tube called a catheter. They feed the tube through a small incision, usually in the leg, then thread it through blood vessels until it enters the leaky valve. The replacement pops open and takes over the job of letting blood out of the heart.

The procedure is called either transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) or transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI).

Doctors don’t know how long TAVR valves last

TAVR is saving lives, and extending them. But the valve’s durability, and longevity remain in doubt.

It was originally developed for people with health conditions that made open-heart surgery risky. Many participants in the original clinical trials were elderly and in poor health, and died within a few years. There isn’t much long-term data on how long the valves last.

Many experts think TAVR valves might stop working sooner than surgically-implanted ones. Compressing the valve may cause microscopic damage, and being squeezed into the heart is hard on the device.

“We have no idea what the durability of those valves is, at all, period,” said Joseph Bavaria, a doctor who co-directs the TAVR program at the University of Pennsylvania, where he is also a professor of surgery.

The companies that make TAVR, including Edwards and Medtronic, say they have good data that the valves last five years. They also say newer valves are more durable than earlier generations.

Younger patients are getting TAVR, even though potential risks are unclear

Even though questions about durability remain, some doctors are putting TAVR valves into younger and healthier patients who may live with the prosthetic for decades.

This practice is already common in Germany and other European countries, ICIJ found. In the U.S., Medicare will only pay for a TAVR procedure if the patient is at medium or high risk of surgical complications, but doctors are free to recommend it to anyone. Manufacturers are currently running clinical trials in patients at low risk of surgical complications.

Cardiologists haven’t dealt with enough broken-down TAVR valves to know how risky it is to fix them. Several prominent TAVR doctors told ICIJ that surgery is still the best bet for most people at low risk of surgical complications, unless they are part of clinical trials.

Doctors have also told ICIJ that degradation of the TAVR valve may cause serious problems, including a need for open-heart surgery when patients are older, more frail and at greater risk of death or serious injury. Several studies have suggested that patients who are good candidates for surgical valve replacement have higher mortality rates if they receive a TAVR valve, instead.

TAVR manufacturers are finding creative ways to market directly to patients

Visit our new website https://t.co/uPZ6qvzqTv to learn how #TAVI can help more #AorticStenosis patients than ever. Get the latest info, download valuable materials, and see the latest innovations at https://t.co/7nVbeiiQfU. #ESCCongress #HCP pic.twitter.com/Z4KCPNemPf

— Edwards Lifesciences (@EdwardsLifesci) August 25, 2018

Manufacturers are donating to advocacy organizations like Mended Hearts and the Alliance for Aging Research, which promote TAVR to patients and government officials. They also buy lots of ads at conferences hosted by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation (CRF), a non-profit that hosts major events for TAVR doctors.

The co-founder of CRF, Martin Leon, also co-founded the first TAVR company. He made at least $6 million when Edwards bought it and then helped run the U.S. clinical trials for Edwards. He says he doesn’t get any money from Edwards now, but acknowledges financial ties to other TAVR-related companies.

Balancing TAVR’s risks and rewards

TAVR has extended the lives of many people, but its long-term durability remains unknown. Patients who may need an aortic valve replacement should talk with their doctors about the risks and benefits of each option.