One of the world’s most controversial fishing operations — a family-controlled company in northwestern Spain linked to more than 40 cases of alleged illegal fishing — is changing tack. Antonio Vidal Pego, co-owner of Vidal Armadores, says the company is folding, and he’s devoting himself to renewable energy and fish oil. But fisheries officials in Brussels are not convinced.

Trafficking in fish is a thriving global black market. It fuels organized crime and the rapid disappearance of the oceans’ most valuable species, including top predators that scientists say are vital to the balance of the marine ecosystem. Nine out of 10 large fish are already gone, marine biologists say.

Many claim Vidal Pego has been one of the most infamous players in this trade – a so-called “pirate” fisherman.

“You can see I don’t have a hook, a parrot on my shoulder or a wooden leg,” the 38-year-old says as he sits down to lunch in a private room at Restaurante Berenguela in Santiago de Compostela, the capital of the Galician region. He says it is his company’s first on-the-record interview.

“We want to erase a story that has never been erased because there’s always someone trying to revive it,” he says. “So much damage has been done by the bad press, we’ve gone from a dynamic company to nothing.”

Vidal Pego — known as “Toño” — says his family business Vidal Armadores, “ship-owners” in Spanish, has been forced to halt operations. He insists that the company has opened a new chapter and moved beyond its controversial past.

When a reporter brings up allegations of his past involvement in the lucrative illegal trade in Patagonian Toothfish — sold in the U.S. under the more appetizing name Chilean sea bass — he says he and his father have only fished legally.

Yet his response leaves room for debate.

The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists has reviewed hundreds of records — including court records, government investigative files and official correspondence — from a half dozen countries. They offer quite another picture – one in which the company has systematically employed legal maneuvers to circumvent international laws.

The ICIJ investigation found that Vidal Armadores or its affiliates have been repeatedly pursued by government agencies and international regulators for its role in a decade-old network of vessels that entered the remote and protected waters of the Antarctic and targeted toothfish in violation of an international convention.

Since 1999, international fisheries regulators have linked vessels owned by Vidal Armadores or its affiliates to more than 40 instances of alleged illegal fishing — more formally referred to by international regulators as Illegal, Unregulated and Unreported fishing — ranging from using banned fishing gear to targeting protected kitefish shark.

While most of the allegations have not resulted in penalties beyond the inclusion of the boats on international “black lists” of vessels, countries from Mozambique to the U.S. have fined the company or its affiliates five times totaling more than $5 million. Vidal Armadores or its affiliates have landed in court six times in criminal or administrative cases related to alleged illegal fishing. Vidal Pego pleaded guilty to obstruction of justice in a U.S. federal court in a 2006 case involving an illegal importation of toothfish by a Vidal Armadores affiliate.

But while accusations of illegal fishing mounted against Vidal Armadores, Spain and the EU granted at least €8.2 million ($12 million) in subsidies to the family’s companies since the mid-1990s, government records show.

The Viarsa chapter

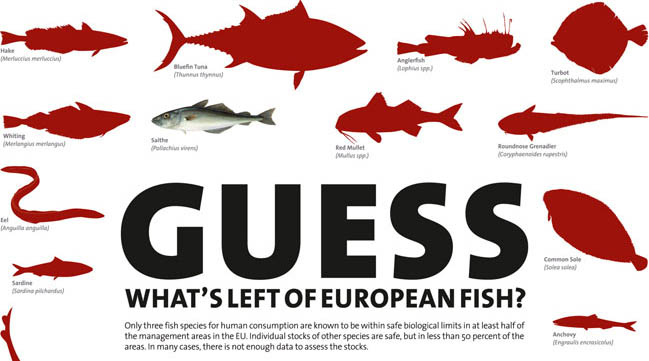

To a large extent the region of Galicia — home to Europe’s largest fishing port, Vigo — is still reliant on fish even though the waters of the European Union are among the most exploited in the world. Three out of four European fish stocks are overfished.

It is here in Galicia that a handful of families have pulled the strings of a transnational network of vessels. And it’s the Vidal family that helped many get into the business by navigating the vessel registration process in Uruguay — a base from which many of the blacklisted ships operated. The Vidals set up offices in Montevideo, hired locals to manage and — when legal claims were brought — to take the blame, court records show.

It was one of those Uruguay-flagged vessels, the Viarsa 1, that put the Vidals on the radar of law enforcement officials around the world.

The Viarsa was spotted in a 2003 suspected illegal fishing operation at Heard Island near the Antarctic Peninsula. The Australian patrol vessel Southern Supporter chased the Viarsa for 21 days almost all the way to South Africa — a chase that ended with the Viarsa being escorted back to Australia. Two years and two trials later, the Vidal affiliate that owned the vessel was acquitted in court. The defense had argued that the toothfish in the Viarsa’s hold had been caught before the vessel entered Australian waters.

The Viarsa chase soon became the subject of a critically acclaimed book. “I know that [the author] had to rewrite the end [when we won!]” Vidal Pego said, with an ironic smile.

According to Vidal Pego, after the Australian authorities lost the case, an international campaign started. “There was tremendous pressure against everything that sounded like Vidal Armadores.”

Vidal Pego is now the face of the company. He is dressed in a black suit, a light pink chequered tie, flashing shiny silver cufflinks and buffed black leather shoes. He is obliging and affable. The only one in the room who is losing composure is Vidal Armadores’ press officer, Foro Hernández, who is repeatedly angered when questions get detailed.

The older Vidal — or “Tucho” — does not join the interview. At 59, he is a legend in fishing circles, a pillar of a clan with a long-standing fishing tradition. He went to sea as a kid, long before Spain joined the European Union, when there were few laws governing how much or where he could fish. He has never spoken to the press except to tell them to “get lost” in that traditional language of the region.

Vidal Pego by contrast spent a year studying in Louisiana, carries a Blackberry and zealously guards his well-buffed image. He says he fears seeing his name in Google searches for the next 10 years whenever someone types “illegal toothfish.”

But while Vidal Pego wants to put fishing behind him, Vidal Armadores continues to attract the attention of authorities. Just this February, fisheries inspectors from New Zealand snapped pictures from a plane as two blacklisted vessels, which had long been controlled by Vidal affiliates, plied their trade in the toothfish-rich waters of the eastern Indian Ocean, European Commission records show.

The Xiong Nu Baru and Sima Qian Baru were flying a North Korean flag — a country not party to the Antarctic fishing treaty protecting the area. The Sima Qian Baru used to be the Vidal Armadores ship the Dorita, flying a Uruguayan flag, according to official blacklists maintained by fisheries regulators. Before that it was the Magnus, flagged to St. Vincent & the Grenadines in the Caribbean. Before that it was the Eolo, flagged to Equatorial Guinea.

Fisheries enforcement officials cite a litany of loopholes that allow vessels to operate with impunity: vast waters to patrol; the use of subsidiaries in tax havens and constant renaming and reflagging of vessels. Flagging to countries such as North Korea, which are not party to fishing conventions, render enforcement authorities impotent when those vessels enter protected zones.

“It’s almost laughable that vessels change their names,” said Keith Reid, scientist with the Commission for the Conservation of the Antarctic Marine Living Resources, (CCAMLR), the body charged with enforcing the rules of the Antarctic fishing treaty. “Often you can see the old name underneath. It’s like a child’s graffiti.”

The Vidals operated the Dorita through subsidiaries in Uruguay and Spain, incorporation and vessel registry records show. After it got in trouble, they changed the vessel’s registration — as they did with other boats — to countries such as Sierra Leone and Panama, which are not members of the Antarctic fishing treaty.

Vidal Pego says the company sold both the Dorita and the other ship currently flagged to North Korea around 2006 or maybe 2007. New Zealand and EU officials have their doubts. So this March, fisheries officials in Brussels repeated in a letter what has become a frequent request over the years — that Spain investigate whether Vidal Armadores continues to control a pirate fishing fleet in the Antarctic.

Patagonian Toothfish

One likely reason the Vidals and others started plying the remote and dangerous waters of the Antarctic was the decline of the cod. When seemingly endless amounts of the fish off Newfoundland, Canada, disappeared in the 1990s after decades of intensive catches, the world’s appetite for white fish had to be satisfied with something else. Boats went further south, and dipped their hooks deeper until they found the big-eyed, mud-brown bottom dweller that now turns a huge profit on the U.S. market. Chilean sea bass is sold for upward of $25 a pound, almost twice as much the price of cod. Its stocks have been heavily fished in the past decade.

Spain is home to the most heavily subsidized fishing fleet in the EU, subsidy data shows.

The country also has a long history of failing to enforce catch limits, inspect vessels or punish fishermen who break the law, according to rulings by the EU Court of Justice. And it has continued to fund companies that had been punished for illegal fishing, according to an analysis of court cases and subsidies data by ICIJ. With one of the world’s largest fleets, Spain also ranks among the top five countries whose nationals register their ships in places like North Korea, which allow them to keep real ownership a secret and ignore international conventions governing huge swaths of the world’s oceans.

Vidal Pego has more than his reputation at stake. His latest venture is an Omega 3 oil factory, Biomega Nutrición, which is slated to receive about €4 million ($5.7 million) in subsidies from the local government and the EU.

“I´m looking forward to providing people better health through fish-oil supplements,” he says. But not everyone thinks he should get the money.

NGOs have protested and so has the European Commission. New European fisheries control legislation enacted last year empowers countries to prohibit public aid from flowing to companies with a history of illegal fishing. Ernesto Penas Lado, director of the Commission’s fisheries policy unit, said he is following the case closely to make sure the regional government of Galicia enforces the new law, which may result in the Vidal family not getting the subsidy.

Throughout the years, Brussels officials have repeatedly pleaded with Spain to “take action against Vidal Armadores” and pursue the recovery of public monies.

Penas Lado said Spain has been “too scared” to act against Vidal Armadores, fearing a drawn out court battle, and too worried it lacked sufficient evidence to win a case.

“These people [the Vidals] will fight to the end,” Penas said. “They say, ‘Hey, why aren’t you giving me the subsidy?’ And they go to court.”

Lucrative trade

The global black market in fish is worth between $10 billion and $23 billion, more than the illicit trades in gold or stolen art. The United Nations categorizes these sophisticated international networks as organized crime. “Like tobacco, trafficking in black-market fish won’t incur the same punishment as drugs or arms. Nobody is looking. Because it’s fish,” said Lt. Cmdr. Daniel Schaeffer, chief of U.S. Coast Guard Fisheries Enforcement. “Any illicit transnational crime is going to be interesting to organized crime.”

The black market for toothfish is an especially lucrative business. A vessel fishing illegally can bring in 1,500 tons in a single season — a haul worth $83 million at a U.S. fish counter.

CCAMLR, the Antarctic fishing regulatory commission, imposes catch limits and drafts regulations against pirate fishing in the southern oceans. Only member countries are legally allowed to fish in the zone, which covers the waters surrounding Antarctica. Boats must be licensed and abide by catch limits. Vessels cannot resupply or transship with blacklisted vessels. Once on a black list, a vessel will find it difficult to dock at many world ports.

“You basically have to be very fast, to get on them before they destroy evidence,” said Marcel Krouse, a South African expert on illegal fishing who assisted in the Viarsa pursuit. “That’s the fundamental problem: The longer the duration between crime and apprehension, the more evidence gets lost.”

And that’s only if they get caught. Otherwise fisheries management commissions like CCAMLR have to rely on diplomatic pressure. “There are a lot of loopholes in the system,” Krouse said. “How are you going to get any response from North Korea?”

Fished out

Illegal fishing is becoming a major threat to fish-stocks in the world. The UN estimates that 85 percent of all fish stocks in the oceans are fished to the very limit of — or beyond — sustainable levels.

There are no longer plenty of fish left in the sea, and scientists warn that killing off too many top predators such as cod or toothfish upsets the ecosystem the same way that taking out a keystone would affect an archway.

Long-lived and slow to mature, a toothfish may be 20 years old before it can reproduce. It is especially vulnerable as fishermen target the large, old fish that produce the next generation. Scientists believe the stock is holding steady but their assessments are limited. Toothfish swim almost a mile beneath the surface in remote oceans, and researchers have to rely on legal fishermen for their data.

The waiters at Restaurant Berenguela empty the plates; Vidal Pego has had hake cheeks with tagliatelle. His take on the scientific reports of steady decline in the world fish stocks is “nonsense.” He says the quantities of hake in the waters off Ireland are bigger than ever; same goes for cod.

Natives of the remote Galician village of Riveira, a town built around the fishing port, the Vidals are politically connected in the region. They have earned the community’s respect for activities such as sponsoring the local taekwondo club or donating money to charities for people with disabilities.

“To me they have always been gentlemen,” said Manuel Torres, a skipper from Riveira. And in cases when their vessels were seized, Torres said, “he got everyone out [of jail]. He paid for lawyers.”

Luis Pazos, Vidal Armadores’ former Uruguayan associate, agrees. “The Vidals are a family of fishermen. They always have been,” he said. “Those men think differently. If you start talking about [illegal fishing], they don’t understand it; they don’t care. Their goal is to fish and maximize production.”

Vidal Pego says that he hasn’t been in the toothfish business since 2006, the year he and one of his affiliates pleaded guilty to criminal charges in a case involving the importation of illegal catches into the U.S. Based on his entry of a guilty plea to one count of obstruction of justice, the judge gave Vidal Pego probation and ordered him to stay out of the trade for four years or risk spending 20 years in a U.S. prison.

Vidal Pego says that he hasn’t been in the toothfish business since 2006, the year he and one of his affiliates pleaded guilty to criminal charges in a case involving the importation of illegal catches into the U.S. Based on his entry of a guilty plea to one count of obstruction of justice, the judge gave Vidal Pego probation and ordered him to stay out of the trade for four years or risk spending 20 years in a U.S. prison.

He says Vidal Armadores itself has never been criminally convicted of illegal fishing. That is true. But Vidal Armadores or its affiliated companies have repeatedly been sanctioned in related legal actions, including more than $5 million in fines for five separate cases.

Two New Zealand fishing inspectors remain troubled by this record.

Paloma V

In May 2008 the Paloma V docked at New Zealand’s Auckland port. More than 200 tons of fish weighed down the boat’s hold: sea bass slated for U.S. dinner plates, shark fins headed to Portugal and fish liver oil for a Japanese cosmetics company. The fishing master had submitted a required declaration that the ship had not done business with pirate fishing vessels. But fisheries investigators Phil Kerr and Dominic Hayden decided to take a closer look.

The Paloma V was half owned by an Uruguayan subsidiary of Vidal Armadores. And Kerr and Hayden knew that a U.S. judge had ordered Vidal Pego to stay away from the toothfish trade.

After copying the hard drives of the Paloma’s computers as part of the port inspection, Kerr and Hayden discovered evidence that they thought might piece together what law enforcement officials from the U.S. to New Zealand had suspected for years: that Vidal Armadores was a central player in a network of pirate fishing vessels targeting toothfish in the Antarctic.

Records from the hard drive showed blacklisted vessels relied on counterparts with legal licenses from places such as Spain, Uruguay and Namibia, the New Zealand investigators found. Receipts found aboard the Paloma V established that Vidal Armadores paid to provision the boats. Photographs showed transshipments to blacklisted vessels. And numerous emails detailed the sharing of bait, fuel and crew.

One of Vidal Armadores’ partners in the Paloma V was interviewed by the inspectors, and they showed him document after document, including photos of the vessel illegally transshipping supplies to the Chilbo San 33 — an earlier incarnation of the Xiong Nu Baru, one of those North Korean-flagged ships spotted this year. Screen-shots from one of the on-board computers showed multiple blacklisted vessels tracked through an online system called Fleetview, suggesting a close coordination among the vessels in the network.

Questions about the Paloma V are the only ones that visibly upset Vidal Pego. He explains that it all was “completely outrageous.” He says the computer was the fishing master’s personal laptop. But the New Zealand inspection file obtained by ICIJ shows three on-board, stand-alone computers were inspected.

To Vidal Pego this case is just more of the same: “There’s no point in talking about fishing, since I haven’t had anything to do with fishing for a long time now.”

Emails found onboard the Paloma V show the company Vidal Armadores allegedly directing a whole network of vessels.

The computers contained emails to and from mantoniovipe@gmail.com (Vidal Pego’s full name is Manuel Antonio Vidal Pego). Vidal Pego dismisses knowledge of the email account or any network: “I — or nobody I know — is in any type of syndicate.”

Vidal Pego says transshipments are common in the high seas because “you cannot go to the supermarket [there].” To him, vessels meet to trade food or even movies — nothing else.

Corporate records also appeared to tie Vidal Pego to the toothfish business well after he promised the U.S. judge he would get out of the trade. Vidal Pego was one of two managers of Vidal Armadores’ parent company, Viarsa Cartera.

“What Vidal was doing was very organized, well structured,” Kerr said. “He had a legitimate fleet supplying the illegitimate fleet. When we saw this material, we saw he was obviously busier than ever.”

International arrest warrant

Of more than 40 allegations related to illegal fishing, the Vidals or their affiliates only landed in court six times.

U.S. officials seized an illegal shipment of their toothfish in 2002. Nothing ever came of that case. In 2004, however, another Vidal vessel, the Chilbo San 33 sold an illegal shipment to a U.S. buyer, according to court records. A federal prosecutor in Miami charged Vidal Pego and one of his Uruguayan companies with doctoring the records to disguise the origin of the fish.

Vidal Pego became wanted on an Interpol warrant and appeared in front of the Miami judge in 2006. His Uruguayan company Fadilur took the brunt of the blame, but Vidal Pego pleaded guilty to obstruction of justice and also agreed to stay away from toothfish.

Today, behind the wheel of his Porsche in his native Galicia, Vidal Pego says he made “many friends” in Miami and that he pleaded guilty only to make the process faster — and less expensive. Thinking back, he says, he should have fought. He’s sure he would have won.

The judgment said that if he in any way broke the law before November 2010, or engaged in the toothfish business, he could end up in a U.S. prison. So when Phil Kerr and Dominic Hayden of New Zealand Fisheries found evidence onboard the Paloma V that Vidal Pego allegedly was still engaged in the toothfish trade — such as telephone calls and email accounts — they quickly sent a copy of the computer hard drives to the United States.

They were surprised when the United States did not issue a warrant for Vidal Pego’s arrest. “We had email links and conversations. We thought there was enough. But for some reason it never happened in the end,” said Kerr.

Assistant U.S. Attorney Thomas Watts-Fitzgerald, based in Miami, could not recall having received any records. New Zealand court records show copies of the hard drives were sent to U.S. officials, and ICIJ pointed out that Watts-Fitzgerald was listed in official records as having sat in on conference calls to discuss the evidence. Watts-Fitzgerald then said, “any discussions of any nature would be law enforcement sensitive,” and directed further inquiry to the press office. The press office later said that Watts-Fitzgerald had no comment.

Off the hook

New Zealand authorities let the Paloma off with a warning instead of opening a time-consuming and legally-complex case against the ship owner. Since its release from New Zealand, the vessel has been seen fishing in Antarctic waters under a Mongolian, then a Belizean and then Cambodian flag, according to fisheries inspection reports. The European Commission suspected it was still a Vidal Armadores boat and in April 2010 sent another “please investigate” letter to Spain’s director general of fisheries. They wanted to know whether the Spanish company was still illegally targeting toothfish.

Vidal Pego claims the Paloma V is not his boat anymore. As for other cases of alleged illegal fishing, he has explanations: there were facts lost in translation; he had been conned into buying a fake fishing license and, in one case, an Uruguayan official wrote the wrong numbers on a U.S. import form.

He only admits to having three vessels with “a problem like this” — meaning illegal or unreported fishing. But later, in the car, he takes it a step further: “Maybe up until 2005 …” he pauses and thinks. “Maybe there was some activity of ours where it could be that a vessel with a flag from another country was fishing and it was inside the [protected] zone.”

Spain reported to international fisheries regulators last fall that it punished Vidal Armadores for the Paloma V’s involvement in illegal fishing — leveling a €150,000 fine ($214,000) and suspending all aid and fishing licenses in Spain for two years.

But the Vidals filed an appeal, so that penalty has not been enforced. The company has also appealed a separate fine imposed by Spain for illegally fishing sharks in Namibia. Notwithstanding the penalties, last year Vidal Armadores received subsidies from the government — this time not to fish hake and langoustine.

The public purse

Juan Carlos Martín Fragueiro was once a lobbyist for a Spanish ship-owners association. In that role, the gray-haired Galician was often seen in the fisheries ministry petitioning for subsidies on behalf of Vidal Armadores and others, according to sources in the ministry and an official exchange on the floor of Spain’s Parliament. Then, in 2004, Martín Fragueiro was appointed Spain’s fisheries secretary.

In total the Vidals have been granted at least €8.2 million ($12 million) in aid since 1996. They got money to fish in places like Comoros and Madagascar, and for an experimental fishing campaign. They even got money to stay at port.

When reached for comment the former fishing secretary denied any relationship with Vidal Armadores or having lobbied for it in the past. Martín Fragueiro said subsidy allocations were decided by committee. “On no occasion have I told the selection committee how it must make the selection. Never.”

Vidal Pego says the company just got what it was entitled to by law.

During his six-year tenure as fisheries secretary, Martín Fragueiro’s office was requested more than once a year by the European Commission to start investigations of suspected infringements by Vidal ships. Some letters were addressed to Martín Fragueiro personally. But for years no sanction was imposed against the company.

Martín Fragueiro said they initiated investigations every time there was a communication and then “we followed faithfully what the legal department told us.”

One example of a Vidal ships getting subsidies, getting caught, and then getting new subsidies is the Galaecia, built with a €1.5 million ($1.9 million) subsidy granted in 2002. Its monitoring system, which assures a boat is fishing where it should, was tampered with in 2003, according to the Spanish fisheries ministry. Vidal Pego says it simply broke. Spain fined the company €42,000 in 2004 but then paid it €1.3 million to fish near the Antarctic as part of a controversial scientific program.

During that same season, EU fisheries officials later wrote to Spain, the Galaecia was seen supplying the blacklisted Dorita (one of the two spotted this year flying a North Korean flag under the name of Sima Qian Baru). Vidal denied that this transshipment occurred. By 2005, six vessels operated by Vidal Armadores had been added to the Antarctic fisheries commission’s black list, according to official correspondence from the EU to Spain.

In one of the letters to the Spanish ministry, then-fisheries commissioner in Brussels Joe Borg begged Spain “for the sake of the credibility of the [European] Community” to pull the Galaecia’s fishing license. Spain took no action, and soon the ship was spotted again transshipping supplies to a blacklisted Vidal vessel.

The ship continued to get subsidies until 2008. That year, while the Commission was investigating whether it had laundered illegal catches, the boat caught fire and sank.

The Commission warned Martín Fragueiro in 2009 that if Spain did nothing, the EU might take legal action, but it never followed up on the threat.

The current Spanish fishing secretary, Alicia Villauriz, told ICIJ that the country’s regulations didn’t allow them to stop the subsidies to the company until they had enough evidence to impose a severe sanction. Spain determined it could finally act in the case of the Paloma V, 11 years after the first allegations of illegal fishing against the Vidals. With an appeal pending, even that action may not come.

Villauriz also said the government can’t recover previously given subsidies unless there is evidence that the money has been misused. “And we don’t have information to think this has been the case.”

Meanwhile, in Mozambique another court ruling is waiting for the Vidals. In 2008 the government seized the Antillas Reefer when it targeted protected kite fish sharks. Mozambique confiscated the boat, converted her to a fisheries patrol boat and imposed a $4.5 million fine. The Spanish government negotiated the crew’s release, but after they had gone home no one wanted to pay the bill. And Mozambique never could collect the fine.

Vidal Pego says his company was a minority shareholder in the Namibian company that owned the vessel.

“Why should Vidal Armadores be responsible for the fine for a Namibian company?” he asks.

As for the two North-Korean flagged vessels spotted earlier this year fishing illegally, the European Commission said that Spain informed it that it is investigating whether the Xiong Nu Baru and Sima Qian Baru belong to Vidal Armadores. But there is nothing new to report. “Given that the investigations usually take time, we will not take additional steps for the time being,” the Commission wrote.

When contacted about this issue, the Spanish fisheries ministry’s reply was a general statement about the country’s commitment to fight illegal fishing. Unfortunately, the email continued, the law doesn’t permit the ministry to talk publicly about sanctions.

Meanwhile in Maputo officials are not giving up as easily. Manuel Castiano, Mozambique’s director of fisheries surveillance is adamant that Vidal Armadores, or Spain, should pay the fines. He is ready for some legal as well as diplomatic action. And he has use for the money.

“$4.5 million is a lot of money, and enough to run my patrol boats a while.”