WALVIS BAY, Namibia — Spanish companies are catching an estimated seven of 10 Namibian hakes in what has been considered one of the world’s richest fishing grounds. Despite warnings that the stock could drop further from an already alarmingly low level, the government of Namibia this year increased the quotas for hake catches. Meanwhile, some players ignore the rules entirely and don’t even bother to hide it. José Luis Bastos, a Spanish fishing magnate, was blunt: “We are over-catching hake, and I don’t have a problem telling the [fisheries] minister this.”

Bastos exceeds quotas without fear of harsh punishment because he is among a dozen well-connected Spanish ship owners who control almost all trade in hake, the southwest African nation’s most lucrative fish. Hake, with its mild taste and tight white flesh, is Spain’s most popular seafood.

Namibia, poor and barren, has a coastline that stretches 1,500 kilometers from South Africa in the south to Angola to the north.

As in the rest of the world, where 85 percent of stocks are fished to — or over — their limits, Namibian hake has been caught far beyond sustainable levels. Estimates are that there are only 13 percent as many hake as swam here in the 1960s. And since the decades-old nation exports most of its affordable fish protein, Namibia is increasingly food poor. A third of its two million people live on less than $1 a day and unemployment is estimated at more than 50 percent.

There are a few groups that escape this desperate situation. Among them: The ruling post-revolutionary establishment and fishing magnates like José Luis Bastos.

From his office in the gritty Namibian port city of Walvis Bay, Bastos explains why he’s not concerned about breaking the law. “If they are going to fine me, they must fine me,” he told reporters from the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. “I’ll see what I can do about the possible penalties.”

He adopted Namibian citizenship to qualify for fishing rights and is confident he can avoid stiff penalties.

As he speaks, Bastos is surrounded by photos of himself with Sam Nujoma, the once celebrated rebel leader who resisted the racist apartheid regime in South Africa to become founding father and president of independent Namibia.

Though no longer president, Nujoma still dominates Namibian politics. Bastos is his frequent host on hunting trips to his ranch. One picture showed Nujoma with a giant kudu antelope he shot there. Not long ago, the ranch covered almost 250,000 acres in the country’s interior, though Bastos says it is now half that size.

About 10 other Namibian-Spanish joint ventures operate in Walvis Bay. The “Wall Street” of fish is what the locals call the long rows of high-tech processing factories with private docks for landing fish in what is among the world’s best-organized whitefish market facilities. The nearby airport was recently upgraded at a cost of €32 million ($45 million) — half of it paid for with loans from the Spanish government — in an attempt to handle cargo jets so fresh hake can be flown to Europe.

“The Spanish are in the veins of Namibia,” fisheries union leader Daniel Imbili said in his office in Walvis Bay. He said Namibia, with scant market knowledge or resources, has little choice but to go along with the relationship.

The town that is a company

Lüderitz, a 12-hour drive south of Walvis Bay, is the only other real fishing port in the country. The name is a reminder of former German colonizers, but these days Spain plays the dominant role. In 1990, at Nujoma’s invitation, the Spanish company Pescanova set up shop there under the name of NovaNam.

Angel Tordesillas, then-general manager of Pescanova in South Africa, steered several of the company’strawlers to the expanding fishing port. Over the next two decades, Lüderitz grew from a population of 12,000 to 32,000. “We can say that Lüderitz is Pescanova,” Spanish ambassador to Namibia Alfonso Barnuevo said.

The investment in Lüderitz earned Pescanova the gratitude of the new nation. Tordesillas fostered a close friendship with Nujoma, then president. And Pescanova has since maintained a close relationship with political leaders. Today the company is the world’s largest supplier of hake, controlling at least 20 percent of the total quota in Namibia in recent years. It is the third largest seafood company in Europe with 2010 sales of €1.6 billion ($2.2 billion).

Anonymous Namibian interests own 49 percent of NovaNam. The rest is controlled by Pescanova, apart from a two percent share in the company held by its workers.

But it is not a happy operation. Employees repeatedly protest poor working conditions and pay. In January, The Namibian reported, 600 workers demonstrated, claiming they were exploited and subject to “slavery.”

“Everybody is afraid of Pescanova,” union organizer Imbili said. “The playing ground is not equal for all. Tordesillas is very powerful in Namibia because he’s [influencing] the government.”

Pescanova operates the largest fishing fleet in Europe and now processes more than 100,000 metric tons of fish annually, but the company is not communicative. It took 14 weeks and more than 25 phone calls and emails before its director of communications answered ICIJ’s request for comment with an email: “We decline the invitation for interviews.”

Where the power is

Bastos and Pescanova are two sides of a coin that bears the same roots: Spain. That’s where most of the fish are going, and so are the profits.

Companies headquartered in Spain with local subsidiaries control about 75 percent of the hake market, according to estimates by industry insiders. Their catches last year would have brought in about 300 million dollars on Spain’s frozen-fish market.

“The fishing industry is dominated by Spain. That’s not a secret,” said Cornelius Bundje, deputy director of the Namibia Maritime and Fisheries Institute in Walvis Bay. “The Spanish are making a profit, and they take it to Spain and other countries.” Imbili agrees: “Billions of Namibian dollars go to Spain. The money is not invested in Namibia. There is not a value adding for Namibia in the fishing industry. … The wealth is leaving Namibia.”

Even the Namibian Hake Association — traditionally chaired by a Namibian — is headed by a Spaniard: Antonio Marino of Tunacor, a joint venture with the Galician company Pescapuerta. The appointment shows the extent to which Spanish interests have penetrated the Namibian ruling class.

Marino denies that there is undue Spanish control of the local industry.

The key to this situation is access to the quotas. To the casual observer, Namibia’s thriving fishing industry is a model of local empowerment: Trawlers all fly the national flag, and at the sound of the 6 a.m. morning whistle local workers walk past flashy new SUVs parked at the factory gates.

The hake industry alone employs 9,000 Namibians — a fact that’s frequently cited to demonstrate the local benefits. Fisheries control is often lauded by international experts as one of the best in the developing world. But a closer look at the hake fishery reveals more disturbing elements.

Foreign companies, mainly Spanish, benefit from political patronage that arbitrarily and opaquely hands out fishing rights to loyal members of Nujoma’s ruling South West Africa People’s Organization (SWAPO), critics say.

All Namibians are potential fishing rights holders, but the Ministry of Fisheries chooses the lucky ones. In the past ten years, only 38 applicants have received hake quotas. When those holders get their fishing rights, they can sell quotas to the highest bidder, usually a Spanish company.

This system has raised questions before, such as when the former fisheries minister Helmut Angula did not deny owning shares in a company that had seen its hake quota increased by 385 percent.

Quota is allocated on a “need” basis, which means applications often list all kinds of women’s groups and marginalized people as shareholders, usually via “development trusts.” This way, empowerment criteria are met but the people whose names are used often never get to see any money, critics say.

“Corruption is a significant component in influencing the allocation of concessions to particular people,” said Namibian fisheries economist Charles Courtney-Clarke. “The Namibian government has been unable to address the dominance of foreign companies in the fishing industry because they [SWAPO leaders] lack a real plan apart from taking advantage of control over resources.”

In a private conversation, a general manager of one of the Spanish fishing companies described how the system works. The Spain-based company owns 50 percent of the local branch; the other 50 percent belongs to Namibian partners. “They have a very high salary per month, but they don’t do any work at all,” he said. “When they pay a visit to our factory, they’re horrified at the smell of hake. But we need them because they are fishing-rights holders. Here we all need this kind of people, for political influence.”

Suso Pérez, another Spanish operator, of Espaderos del Atlántico, said the local partners are figure-heads cashing in on their political alliances. “They’re all members of SWAPO who have no bloody idea about fisheries.”

Fishing to the limit — and over

That Bastos so freely acknowledged overfishing his quota was because, he said, it was simply too low. “We informed the minister that the resources are fine, we are catching in record time,” he said. “We need quantity to be able to survive. I hope that the minister will take that into consideration when they decide the quotas.”

Bastos said that what’s needed is more quota and less competition. In his view, too many things get in the way of fishermen’s bottom line.

Sustainable fishing relies on scientifically based quotas — how much fish you can take without actually killing off the population. But the most common problem in the world’s fisheries is that scientific evidence has not been heeded by politicians and fishermen.

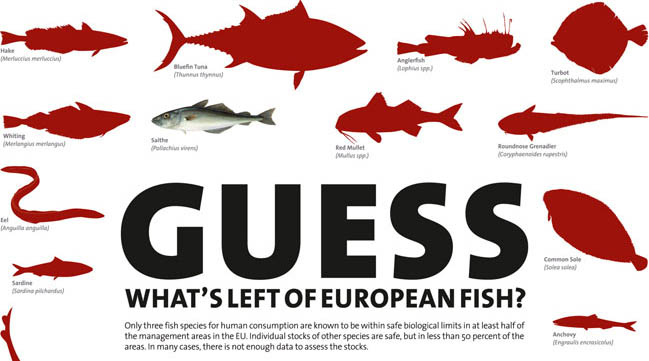

And here Namibia fits into the larger and much direr global picture. The last assessment of world fish stocks from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concludes that 85 % of world fisheries are fished to their maximum, overfished or depleted.

Namibia became a textbook case of that phenomenon when Spanish trawlers first started plundering hake in Namibian waters in the 1960s. They hauled out so much fish that by the time Namibia won independence in 1990, the stock was only at an estimated 13 percent of its original level.

Since independence Namibia’s rulers have gotten a better grip of the valuable resource. The stock is no longer declining, scientists say, but it’s still a fraction of what it was, and it’s fished to its biological maximum.

Each year, the government-controlled Namibian National Marine Information and Research Centre (NatMIRC) gives advice on biologically acceptable levels of outtake for each fish species. But the fisheries ministry often yields to industry pressure and sets a higher quota, critics say.

“Misrepresentation of statistical information to justify increases in quota is common knowledge,” said fisheries economist Courtney-Clark about local stock assessments.

This spring the scientists at the research center set the biologically acceptable quota of hake to a maximum of 145,000 metric tons for the 2011-12 season, but then the fisheries ministry decided to raise it.

“The minister decided on 180,000 tonnes, probably considering socio-economic factors,” explained Carola Kirchner in an email. She was a stock assessment scientist in the Namibian government for 18 years until she recently resigned. “Whether the stock will sustain catches of this magnitude is questionable. … In my opinion it was not a very good idea. … This will seriously backfire at some stage.”

Kirchner’s assessment is that the stock will decrease again. “They can completely go against the center’s advice. … We have to quietly accept the decisions.”

The ministry acted under significant pressure from industry. In April, almost all hake fishing companies halted operations and laid off workers in protest for what they considered a low quota. “What they are trying to do is blackmail me,” Bernhard Esau, minister of Fisheries and Marine Resources told the Windhoek Observer at the time. Esau did not return calls, emails and written requests for interviews from ICIJ.

In the end, and despite its own misgivings on overfishing the stock, the Namibian ministry of fisheries increased the hake quota by 29 percent above the previous year’s 140,000 metric tons. The increase went against the NatMIRC scientists’ recommendation that “variations in the [quota] must be capped at 10%.”

In their latest stock-assessment report the scientists say that what little is left of the stock is still vulnerable and that “the fishery should be managed by using the precautionary approach.”

One Word: Fish

Ten hours’ drive inland from Lüderitz and the coast lies Namibia’s capital, Windhoek. There Carmen Sendino heads the Spanish Cooperation Office, the Spanish government’s aid organization.

Spain has encouraged its industry’s monopoly of the Namibian hake industry, exchanging a dozen official state visits in as many years to discuss the sector. Spain subsidized the transfer of Spanish-flagged vessels to Namibia and then pressured the government to ignore invitations from the EU to enter into fishing agreements that would allow other European fishing fleets into its waters.

Also, since 1997, the NatMIRC’s research projects have been financed by the Spanish government and the region of Galicia.

The generosity has to do with one thing — the presence of the Spanish seafood companies. Sendino was reluctant to comment on the details in the relation between the Spanish aid and the fishing sector, but she said one word that summarizes it all: “Pesca,” Spanish for fisheries.

Spain has handed out millions of dollars in aid to Namibia — some of it directly to the fishing industry. The last available figures indicate that from 2006 to 2009 Spain’s aid to the country was worth in excess of €50 million ($70 million), according to data from Spain’s foreign affairs ministry.

“Spain is supporting the Namibian government, and they pay back this aid through the hake industry,” said Imbili, the union leader.

According to Peter Pahl, managing director of Namibian-run fishing company Seaworks, the aid and subsidies from the Spanish government are used to lobby on behalf of its companies for fishing rights. “The Spanish government is lobbying Namibia. In this sense, Madrid’s government is being very proactive.”

The Spanish Secretariat for International Cooperation told ICIJ in a statement that the aid is not meant to favor the Spanish fishing companies in Namibia but “to strengthen the Namibian fishing sector,” which represents a quarter of the country’s exports income.

As relationships go, Nujoma’s and Bastos can be said to be fairly close. In his picture-filled office, Bastos confided to us about a favor he is doing for “the old man,” as Bastos usually refers to Nujoma.

“I am building a house for him,” said Bastos, and showed a power of attorney from the former president to deal with the development.

The house will be located on a prime piece of land situated in what is locally referred to as “the Millionaire’s Mile” along Walvis Bay’s flamingo-flecked lagoon.

On parting, Bastos added that he never asked Nujoma for any favors.