Along the Mediterranean coast of France, in the city of Montpellier, prosecutors are quietly putting on trial an ancient French tradition — the fishing and trading of the majestic Eastern Atlantic bluefin tuna, a sushi delicacy sold in restaurants from New York to Tokyo. The still-secret proceedings accuse some of France’s most prominent fishing masters of illegally catching several hundred tons of the prized bluefin, a fish so severely plundered in the Mediterranean that this year it was proposed for listing as an endangered species alongside panda bears.

Bluefin tuna is one of the sea’s most valuable species, a highly migratory fish that can weigh more than 500 kilograms and live 40 years. One large fish can fetch more than $100,000 in Japan, which consumes around 80 percent of the global bluefin market. The widely hunted bluefin has also become a bellwether, the latest threatened species in a feeding frenzy that has seen the disappearance of as much as 90 percent of the ocean’s large fish.

The fishermen, for their part, say they were part of a culture that manipulated national catch figures to shield France’s bluefin fishing industry from international scrutiny. They charge that the real culprit is missing in the courtroom: their nation’s Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries.

In fact, in what has become one of the world’s most notorious fisheries, France is just one player — and there’s plenty of blame to go around.

As regulators gather in Paris later this month to decide the fate of the Atlantic bluefin, a seven-month investigation by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists has found that behind the plummeting stocks is a decade-long history of rampant fraud and lack of official oversight. Each year, thousands of tons of fish have been illegally caught and traded. At its peak — between 1998 and 2007 — this black market included more than one out of every three bluefin caught.

The questionable practices extend across the industry, ICIJ found, from fishing fleets and farms, through ministry offices, to distributors in Japan. Led by the French, Spanish, and Italians, joined by Turks and others, Mediterranean fishermen violated official quotas at will and engaged in an array of illegal practices: misreporting catch size, hiring banned spotter planes, catching undersized fish, and plundering tuna from North African waters where EU inspectors are refused entry. An illicit market even arose in trading quotas — when regulators finally started enforcing the rules — in which one vessel sells its nation’s quota to a foreign vessel that had overfished.

The bluefin black market is not a surprise to some experts. “Fisheries are one of the most criminalized sectors in the world,” said Daniel Pauly, a marine biologist at the University of British Columbia, who was one of the earliest voices to warn the world about the impact of commercial fishing on marine ecosystems. “This generates so much money that it’s like drugs.”

Though not always an outright criminal market, the pervasive lack of accountability and the widespread practice of lying about catch amounts have given rise to an off-the-books trade conservatively estimated at $4 billion in revenue between 1998 and 2007, according to an analysis by ICIJ. The analysis was based on official estimates of total catch, Japan wholesale market prices, and official quotas, the limits issued to countries of how many fish they can catch in a single season.

This black market has been abetted by a host of officials, from overworked local inspectors to international regulators — most notably the International Commission for the Conservation of the Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT), a regulatory body set up to protect the bluefin stocks, which frequently ignored its own scientists’ recommendations for smaller fishing quotas and tighter controls.

“There was just no political will to enforce the rules, most notably the quota,” said Jean- Marc Fromentin, a marine biologist and a member of ICCAT’s scientific body. “Until 2008 … there was no enforcement. No one declared. There was general cheating.”

As a result, the Eastern Atlantic bluefin spawning stock has plummeted by nearly 75 percent over the past four decades, with more than half of that loss occurring between 1997 and 2007, according to ICCAT figures. Today fleets are down to much smaller fish, including juveniles, further curtailing the chances of the stock to recover. Some scientists believe that continued lack of controls and generous quotas could result in wiping out the entire adult bluefin population.

Biologists warn that at stake is more than the mere loss of a favorite source of sushi. Bluefin tuna, they say, are near the top of the food chain and their demise will have dire consequences for marine ecosystems. Without large predators, entire food chains may erode, leaving the seas overrun by millions of jelly fish and micro-organisms.

Alarmed at the rate of bluefin decline, ICCAT regulators came up with a new paper-based reporting system in 2008 designed to help them better track the trade and deter the black market. But the system — dubbed the Bluefin Tuna Catch Document Scheme, or BCD — is full of holes, rendering the data almost useless, the ICIJ investigation found. Officials have also launched a belated crackdown on the illicit trade, but it is helping push the bluefin industry to renegade fleets in North Africa and Turkey.

The ICIJ inquiry relied on more than 200 interviews with fishermen, ranchers, divers, officials, scientists, and traders, as well as court documents, regulatory reports, and corporate records in ten countries, including France, Spain, Japan, and Tunisia. In addition, ICIJ gained access through an ICCAT member country to the commission’s internal BCD database and ran an extensive analysis of the data.

Fraudulent fleets, complicit officials

For decades, the market for Mediterranean bluefin tuna remained modest and largely regional. That changed in the 1980s, when the Japanese developed a taste for toro, the fatty belly flesh of the bluefin. What followed was the rapid development of a heavily subsidized EU fleet of specialized “purse seining” vessels, which vastly expanded catch size by using giant nets that can trap as many as 3,000 fish at a time.

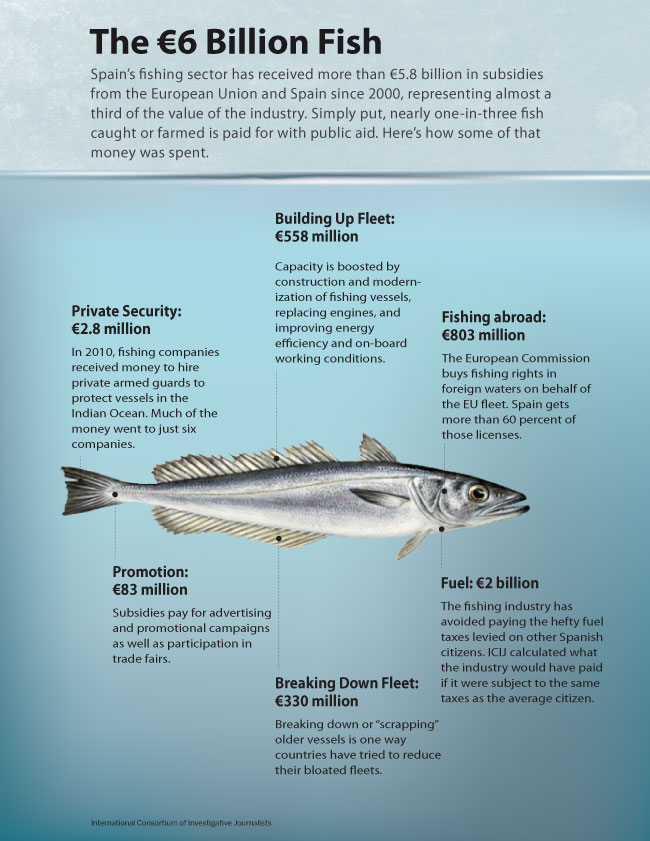

Over the past decade, more than €800 million of aid poured in yearly from the EU and member states to the overall European fishing industry, helping build overcapacity in the Mediterranean fleets.

ICCAT established the first country quotas in 1998, just as Spanish and Croatian fishmongers revolutionized the industry by setting up what were called “farms” — sea ranches, really — in the Mediterranean, where the fish are fattened for months before being shot in the head and shipped to Japan.

Soon the market ballooned — the Japanese were willing to pay big for bluefin, and the fishermen needed the money to repay bank loans for their vessels. Until 2003, the cost of fishing, transporting, and fattening a bluefin tuna peaked at 12 euros a kilo, but it was sold to the Japanese for at least five times that amount. Scientists and fishermen call the period between 1997 and 2007 “the jungle” — a time of blatant overfishing and rule-breaking.

Joining the EU fleets was ICCAT member Turkey, which ran a large, dilapidated fleet notorious for flouting the law. Meanwhile, North African states — Algeria, Libya, Egypt, and Tunisia — sold EU vessels entrance into their rich, unregulated waters in exchange for a cut of the catch, fishermen say. The result: annual catches jumped to 50,000 to 60,000 metric tons — almost double a typical quota of 30,000, according to ICCAT estimates, and three times what ICCAT scientists deemed sustainable. In 2007, the bluefin fishery spawning stock hit a record low — 78,724 tons, less than a third of its peak in 1958.

The widespread rule-breaking made it nearly impossible to crack down. “From the moment a person commits fraud, when he fills out false documents, then there is absolutely no way to control the fishery,” said French prosecutor Patrick Desjardin, who is heading the investigation into illegal fishing by French fishermen.

Worsening matters was the apparent complicity of government officials. Even when fishermen fully declared their catches, the national numbers were later “fixed” at the ministry level, which is responsible for transmitting the official country catch to EU regulators, according to officials and industry sources.

Joseph Salou, the former head of the fishing trade association Sa.Tho.An, in Sète, said the decision over what catch figures to declare to EU regulators was a “collaboration” between industry groups like his and officials with the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries in Paris. “It was a discussion we had every year, the administration and the industry, because the administration was also complicit,” said Salou, who participated in the talks.

An official in the ministry, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to preserve his job, said he had expected investigators to knock on his door and demand why he and others had done nothing to stop the illegal fishing. “People at the ministry at the time knew that if the police did their job, sooner or later they would be asking about the government’s role,” he said.

But that visit never came.

The situation reached a head in 2007 when France declared its real catch: nearly 10,000 tons — almost double its allowed ICCAT quota for the year. Publicity around the overfishing triggered a criminal investigation, resulting in charges in Montpellier against the six fishermen. No French officials have been charged.

ICIJ made a dozen written requests to the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries asking that it respond to allegations that its officials colluded in doctoring catch data. The Ministry never responded.

Ranching: bluefin black holes

Since they started to appear in the Mediterranean in the mid-1990s, ranches became the epicenter of some of the worst excesses in the Atlantic bluefin tuna fishery. Today there are more than 60 ranches spread across the Mediterranean, many in laxly-regulated places like Tunisia, Cyprus, and Turkey. Together, they hold the capacity to process nearly three times more fish than fishermen have been allowed to legally catch in recent years.

As Japanese demand for bluefin increased, these opaque underwater labyrinths of nets and cages, where counting fish is almost impossible, became the perfect counterpart to the out-of-control fishing fleets. Much of the fish illegally caught in the past 15 years in the Mediterranean was laundered at the farm level, industry insiders say.

As Japanese demand for bluefin increased, these opaque underwater labyrinths of nets and cages, where counting fish is almost impossible, became the perfect counterpart to the out-of-control fishing fleets. Much of the fish illegally caught in the past 15 years in the Mediterranean was laundered at the farm level, industry insiders say.

Behind the shift to sea ranching were the Japanese. Leading Japanese trading houses and seafood companies like Mitsubishi Corporation and Maruha helped set up and fund a ranching system that by the late 1990s was supplying more than half of Mediterranean bluefin. Francisco Martinez, who in 1994 opened the region’s first ranch in Cartagena, Spain, said the Japanese financed the fishing campaigns in advance, and provided technical support to set up the cages and test the quality of the fish. In Croatia, Mitsubishi underwrote loans for its trading partners.

Ranching forever changed the nature of the Atlantic bluefin trade. Instead of catching the fish, killing them, and returning to port, vessels transferred live fish from their nets into cages, which slowly towed the fish to ranches to be fattened. But because the entire process happens under water, with live fish swimming about, ranching made it nearly impossible to verify the weight or number of fish caught.

At the ranches, various ways emerged to “launder” fish, according to interviews with ranchers, divers, and inspectors. Techniques included under-declaring the amount of tuna acquired, killed, or traded; mixing legal catches with illegal catches; exaggerating the fattening rates of tuna to account for the extra weight of illegal fish; and transferring illegal fish to ranches in less regulated states. “For the fish that are over quota, you have to find a solution” at the end of the season, said a former manager for a leading Spanish rancher. “You either trade it illegally or keep it until the next season … We took the over-quota fish to Tunisia.”

After years of no-questions-asked, Japanese officials have started to balk at the excesses of the ranching industry. In 2009, Japan refused entry of more than 3,500 tons of suspicious shipments of Atlantic bluefin tuna — about one-sixth of the country’s supply that year. All but 800 tons were eventually allowed in, but the Japanese were making it clear that it would not longer be business as usual. Among the problems Japanese inspectors found: ranch tuna were fattened at rates that were biologically impossible, and some ranches tried to export more fish than vessels had supplied to them. “This is incomprehensible, no matter which way you look at it,” said Masanori Miyahara, head of the Japanese delegation to ICCAT. “It is not as if the fish lay eggs and propagate while in the pen. We said this is nonsense.”

In fact, ICIJ’s analysis of the Bluefin Tuna Catch Document database, the reporting system established by ICCAT to track the trade, shows that in 2008 and 2009 more than a dozen ranches in the Mediterranean appear to have somehow killed more fish than they acquired. The analysis also found that at least 20 percent of the tuna that ranches reported killing at their facilities during those years — some 118,000 fish — lack export information, effectively turning those fish into ghost tuna that regulators can’t track to their final destination.

One ranch attracting attention from authorities is Drvenik Tuna, a Croatian facility co-owned by the Cartagena, Spain-based Ricardo Fuentes & Sons, an industry pioneer which operates farms around the Mediterranean, including Malta, Tunisia, and Cyprus. Drvenik Tuna is jointly owned by Fuentes, Japanese trading giant Mitsubishi, and local partner Conex Trade. Drvenik has drawn criticism since its founding in 1998. Among the official complaints were setting up a ranch without proper authorization and operating a vessel without valid documents, according to enforcement records and interviews. Environmentalists have also complained that the company polluted nearby waters by dumping fish remains. Mitsubishi said Drvenik is “in full compliance with local and ICCAT regulations.”

In December 2008, Drvenik Tuna was forced to release 712 bluefin caught by French vessels after officials ruled the fish were illegally underweight, according to an ICCAT compliance report and Croatian officials. A year later, Japanese officials refused to allow the import of 560 tons of bluefin caught by two Algerian vessels and fattened at a Fuentes ranch in Tunisia because the fish had no accompanying documentation, according to ICCAT compliance records. Again, Fuentes was ordered to release the fish.

A Fuentes manager in Tunisia, Amor Samet, acknowledged the incident and said the Algerian fisheries ministry refused to validate the catch due to “problems” with the fisherman involved. The episode prompted Japan to temporarily halt imports of bluefin tuna from Tunisia in 2009.

A half-billion dollars of bluefin

The trail of the bluefin tuna ultimately leads to Japan, whose avid fish eaters comprise the world’s biggest market. Although not the size it once was, Japan’s Atlantic bluefin market was valued at more than $500 million annually last year.

The popular image of Japan’s bluefin tuna industry is Tsukiji, the world’s largest fish market in central Tokyo, where tuna are auctioned off each morning in a dizzying array of nods, winks, and arcane signs. But most tuna are not auctioned these days; they are sold directly to buyers and distributed through an intricate web of trading houses, brokers, importers, processors, wholesalers, and retailers. At the top of this well-oiled distribution system sits Mitsubishi. Better known for trading in cars, chemicals, and steel, the corporate giant owns subsidiaries that control about 40 percent of the bluefin market in Japan.

To feed their ravenous tuna market, the Japanese also import a large amount of southern bluefin, a sister species to the Atlantic bluefin from the southern oceans. Worried that Japan’s fishing fleet was fast depleting the southern bluefin, in 2006 Australian officials joined with their Japanese counterparts in a three-month-long inquiry. The final report proved to be a damning indictment of Japan’s tuna fishing industry, as well as of the government in Tokyo, whose poor controls had allowed massive imports of bootlegged bluefin into Japan. So embarrassing were the findings that the report was kept secret and its researchers were made to sign non-disclosure agreements.

ICIJ has gained access to the report, modestly titled Independent Review of Japanese Southern Bluefin Tuna Market Data Anomalies. The study reveals two decades of overfishing of southern bluefin tuna by Japan, with widespread sale of under-reported or unreported catches. Japanese traders “laundered” bluefin by importing it as cheaper species and then renaming it at the marketplace, the study found. “What we were talking about was a minimum $6-$7 billion [Australian dollars] of illegal catch, a lot of jobs, and the international humiliation of Japan,” said an Australian tuna industry source knowledgeable about the study.

As a result of the report’s findings, Japanese quotas of southern bluefin tuna were cut by half. But the no-questions-asked policy of Japan’s importers and regulators changed little until recently. “The Japanese are the designers and financiers of the Mediterranean farming system,” said Sergi Tudela of the World Wildlife Fund, an environmental group. “Now the system is out of control, and they are scrambling to distance themselves from it.” In 2008, responding to concern about plummeting bluefin stocks, Mitsubishi pledged to work toward a more sustainable fishery. “We will not purchase bluefin tuna from suppliers who do not meet our requirements, or who are found to be in violation of applicable laws and regulations,” reads a company statement.

BCDs: “A Bloody Mess”

As officials in the Pacific suppressed their own report on southern bluefin, environmental outcry over the fate of Eastern Atlantic bluefin was building in Europe. In 2006, ICCAT launched a 15-year plan to replenish the stock by reducing quotas and increasing the minimum catch size. But the limits outlined were still twice as high as ICCAT’s own scientists recommended.

Fisherman used to years of hands-off treatment were slow to believe the rhetoric of a crackdown, even when quotas for individual vessels were added alongside national quotas in 2008. “No one thought we were really going to have to respect the quota,” French fisherman Nicolas Giordano recalled. “They said, ‘We’ll fish what we want, and we’ll see what happens.’” Other fishermen say they responded by colluding even more closely with their ranching partners to launder the overcatch. They also increased profits by selling quotas in places like Malta and Turkey.

In 2008, ICCAT commissioned a panel of independent auditors to review its performance. Their report condemned ICCAT’s member countries for having “failed to abide by their legal obligations…failed to conserve bluefin tuna and failed in the eyes of the international community.” But their dramatic call for the immediate closure of bluefin fishing and ranching was ignored.

Instead, ICCAT launched the Bluefin Tuna Catch Document Scheme (BCD), a program that the European Commission lauded as bringing “complete and reliable traceability” to the trade. Under the BCD system, vessels are given a unique number for each catch, which follows the fish to ranch, through harvest, and finally to market. All along the supply chain, players are required to provide detailed information about the number, size, and location of the fish. The hand-written documents are validated by national fisheries authorities and submitted to ICCAT, where the data are manually entered into a database.

ICIJ gained access to the BCD database through an ICCAT member country and found the system riddled with incomplete information and discrepancies. For example, during 2008 and 2009 more than 75 percent of all purse seiner catches — which comprise nearly half of the overall catch — are missing crucial information that regulators need to follow the fish from vessel to market. For example, the US imported nearly 500 tons of bluefin during those two years, yet not a single kilo is accounted for in the database. When asked by ICIJ about the missing import data, US officials said they were unaware the information was not in the database. “That’s kind of something I’m having trouble understanding. Because we report that,” said Rebecca Lent, director of International Affairs for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Then there’s the backlog — as of June this year, catch data for 2008 were still incomplete. Asked about shortcomings in the database, ICCAT executive secretary Driss Meski said he was unaware if the data entered were incomplete or inconsistent.

ICCAT’s compliance chair, Christopher Rogers, attended a meeting in February along with Mr. Meski during which they discussed the backlog. He said his committee considered trying to analyze the database earlier this year, but gave up because the data was so incomplete.

With the Japanese starting to reject fish without properly filled BCDs, industry sources say the forms have become as valuable as the tuna. Industry sources say a new scam has emerged — faking fishing operations to obtain a validated BCD. “If you have tuna, but you don’t have documents, then you don’t have tuna,” explained one rancher. “You can always sell the form to the highest bidder.”

“It’s just a bloody mess,” said ICCAT scientist Fromentin of the BCD system.

A culture of secrecy

A wall of secrecy protects the bluefin industry. “I can understand there is a need for transparency,” Maria Damanaki, the European Commission’s top fisheries official, told ICIJ. “If any case is complete, you should have the full data.”

Yet ICIJ requests to the European Commission for records on fishing and farming infringements were routinely denied. The commission took 48 days — three times longer than regulations allow — to answer a freedom of information request by ICIJ on bluefin fishery infraction records. The Commission denied ICIJ access to the data citing protection of commercial interests and even “military matters.”

Response at the national level was no better. In Spain, the Ministry of the Environment and Rural and Marine Affairs refused to release details on administrative actions taken against bluefin fishery offenders. In Croatia, officials failed to produce fishing inspection records of vessels and ranches. In Turkey, officials canceled an interview to discuss compliance issues.

Illicit catches, meanwhile, remain a serious problem. In southern Italy last month, officials seized a catch of 500 baby bluefin weighting an average of just one kilo. And in North Africa and Turkey, even less accountable fleets are ramping up operations. Ranking officials in Algeria’s Ministry of Fishing were convicted this year of trafficking in contraband tuna, influence peddling and tax evasion ina 2009 case involving Turkish vessels illegally fishing in Algerian waters. Four Algerians — including the ministry’s secretary general — and five Turkish fishermen were sentenced to prison terms and fined €80 million.

ICCAT officials contend that enforcement has increased significantly, including its deployment this year of observers on all purse seiners fishing in the Mediterranean. But the observers complain it is almost impossible, standing on ship decks, to provide an accurate estimate of catches, according to an evaluation report commissioned by ICCAT. They must instead rely on the crew’s estimates, and on video footage that vessels and farms often do not provide.

This lack of reliable data has a direct impact on marine scientists who are trying to assess the state of the declining bluefin stock. “We don’t know how much we know, so we can’t even put bounds on the uncertainty,” said Justin Cooke, a fisheries population mathematician hired by the environmental group WWF.

Based on the data he has seen, Cooke believes that purse seining should be suspended in the Mediterranean until a better assessment can be made. But when ICCAT members meet in Paris this month to decide the future of the fishery, they will hear a different story. ICCAT scientists have decided to recommend a fishing quota of up to 13,500 tons annually through 2013, despite their own admission that the data they use to assess the bluefin stock has “considerable limitations.”

The European Commission’s Damanaki — newly installed and widely seen as a reformer — says she is determined to do anything needed, including supporting a fishing moratorium, to protect the fishery.

“Not because we love fish more than fishermen,” she quickly clarified. “But if there are no fish, there will be no fishermen.”

A companion documentary, “Looting the Seas,” produced by ICIJ and London-based tve, appears on BBC World News on November 6-7, 2010.