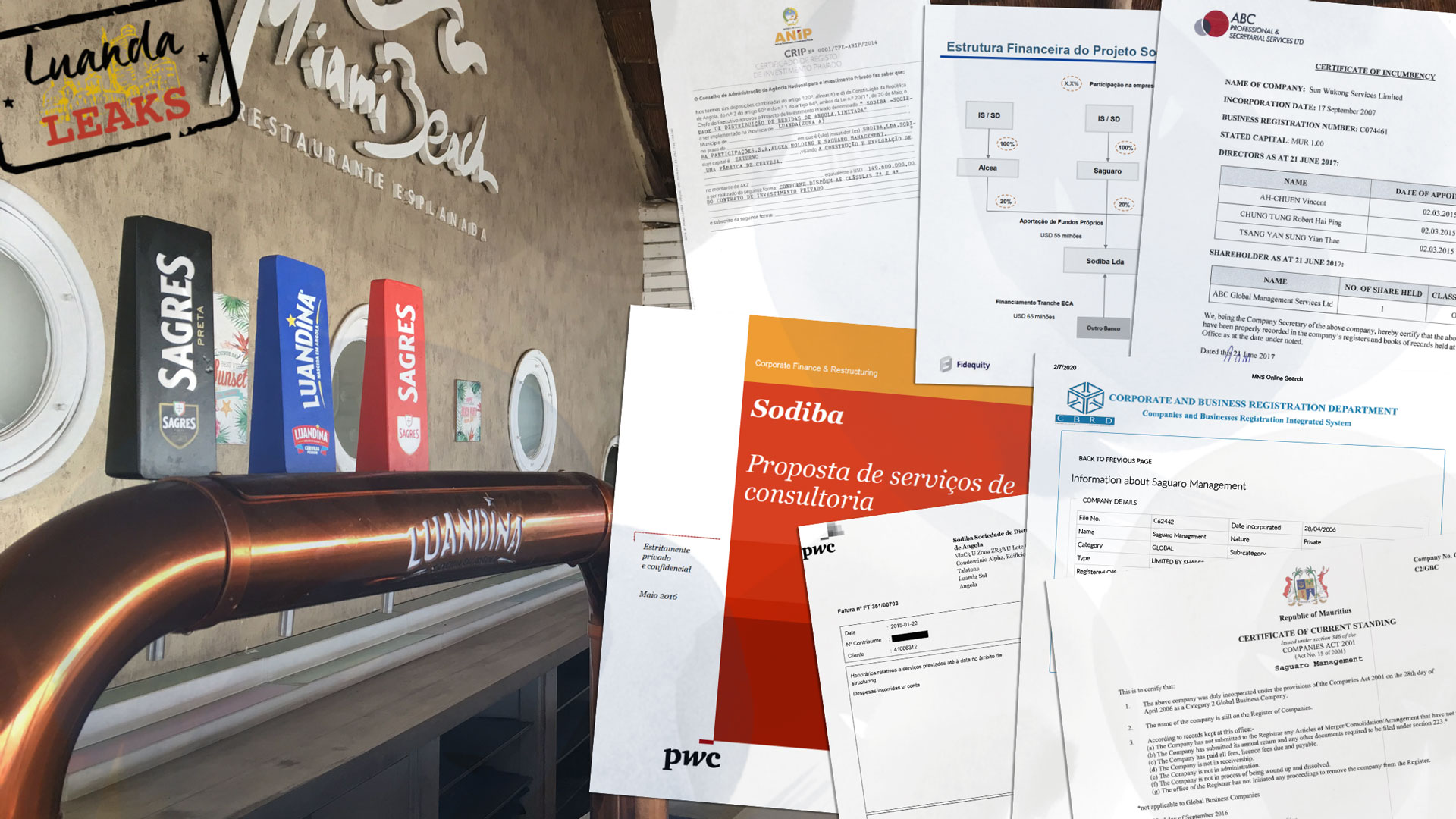

In the dry, warm Angolan autumn of 2014, billionaire Isabel dos Santos and her husband, Sindika Dokolo, dreamed of beer. Lots and lots of beer.

Dos Santos, the Angolan president’s favorite daughter, had long pined for a brewery of her own to break into the southern African country’s lucrative drinks market. Angolans have a “happy-go-lucky attitude towards life” that favored a new competitor, according to a confidential project memo prepared by bankers backing dos Santos. The brewery, in Bom Jesus, 40 miles southeast of Luanda, could generate $80 million in sales by 2021, bankers predicted.

Dos Santos’ brewery would serve Angola’s elite and working-class with local brands and the well-loved Portuguese lager, Sagres, owned by Dutch giant Heineken. It would produce 1.2 million hectoliters of beer a year, according to predictions. Her father’s government had already endorsed the venture by granting her company a 10-year income tax holiday.

The brewery masterplan hinged on one of the couple’s favorite business entities: shell companies. This time, companies in Mauritius, the small island tax haven off the east coast of Africa, would be key. The couple owned or held shares in eight companies on the island, according to an analysis by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists.

The role of Mauritius in the dos Santos empire is revealed through Luanda Leaks, a trove of financial and business records obtained by the Platform to Protect Whistleblowers in Africa and shared with ICIJ. Analysis of the documents by ICIJ and its media partners reveals the inside story of how Africa’s wealthiest woman moved hundreds of millions of dollars in public money out of one of the poorest countries on the planet and into a labyrinth of companies and subsidiaries, many of them in offshore secrecy jurisdictions around the world.

Despite its small size, said Mustapha Ndajiwo, a former Nigerian tax official and founder of the African Center for Tax Governance, “Mauritius maintains its reputation as one of the most notorious tax havens.”

Dos Santos’ father, José Eduardo dos Santos, ruled Angola for 38 years, and has remained an influential figure since retiring from the presidency in 2018.

Her business dealings with Mauritius is an example of how offshore havens — often populated by accountants and lawyers and other operatives from the United Kingdom, the United States and other wealthy nations — help the mega-rich and corporations shield their assets from African tax collectors.

Jason Rosario Braganza, a Kenyan economist and tax justice advocate, told ICIJ that the financial dealings unearthed through Luanda Leaks are “a vivid reminder that it is not ‘corrupt Africa’ but instead complicit ‘Europe and North America’” that drive “the willful undermining of domestic laws and regulations.”

Dos Santos’ beer plan, prepared with the aid of London-headquartered tax advisers PwC and one of Mauritius’ richest families, involved funding from banks, private investors and the Angolan government.

Dos Santos and Dokolo would also invest in the new Angolan company, Sodiba Lda., through three of their companies, according to a PowerPoint presentation. The first, Sodiba SA, was in Angola. The second, Alcea Ltd., was registered in Malta at a five-story office building not far from a beachfront casino. Saguaro Management Ltd., the third and most secretive of all, was in Cybercity in central Mauritius.

Saguaro Management, created in 2006, was key. A document from Luanda Leaks, signed on Sept. 21, 2016, confirms that a second Mauritius company, Sun Wukong Services Ltd., held shares as a “nominee” in Saguaro Management for dos Santos and Dokolo. This arrangement made sure dos Santos’ name would not appear on public documents, but guaranteed the couple full control of the company and of any money it made.

Mauritius does not keep a public record of who owns companies on the island. The only information published online about Saguaro Management is its official address and the date it was created.

Adam Hofri-Winogradow, an expert in the law of offshore jurisdictions at Hebrew University of Jerusalem, said the secretive structure was “pretty shabby planning” that was clearly “intended to disguise Ms. dos Santos’ interest in the company.”

Mauritius is a well-known trust destination, said Hofri-Winogradow. His recent research shows that Mauritius ranked fifth among jurisdictions outside the United States that impose few, if any, restrictions on a person’s freedom to design a trust.

“The higher the ranking, the more devices and tricks the law of the jurisdiction in question offers,” said Hofri-Winogradow.

Mauritius denies that it is a tax haven. The government has previously told ICIJ that it “is compliant with international norms and standards.”

Helping dos Santos and Dokolo become Angola’s newest beer barons was ABC Global Management Services.

ABC is part of the ABC Group, also the island’s official distributor of Porsches and Alfa Romeos and one of the most profitable vendors of cheese, chocolate, corned mutton and other foodstuffs to hotels and supermarkets. Founded in 1931 by a former government minister, ABC Group today employs more than 1,300 people.

ABC Global Management Services, the group’s offshore arm, helped dos Santos and Dokolo administer Saguaro Management from as early as 2006, according to Luanda Leaks records. Those records also show that, from early 2015, Vincent Ah-Chuen, son of the ABC Group’s founder, served as a director of Sun Wukong Services, the “nominee” shareholder for the couple in Saguaro.

Jean Claude Tsang, ABC Global’s general manager, told ICIJ that the company could not respond to questions on its work with dos Santos due to confidentiality and data protection obligations.

Responding to questions from ICIJ’s media partner in Mauritius, L’Express, ABC’s lawyers said that the firm had complied with relevant laws and regulations. ABC’s lawyers warned the L’Express reporter that they would “take legal action against you personally and your newspaper” if he published documents from Luanda Leaks.

Angola’s power couple used Mauritius for more than a beer empire. Other Mauritius firms happily offered their services, documents from Luanda Leaks show.

In April 2015, for example, dos Santos went shopping. Besides the diamonds, midnight blue-toned pumps and dark ruby lambskin iPhone covers she bought from Dolce & Gabbana – customary fare for the billionaire – dos Santos wanted another shell company in Mauritius.

In a series of emails, Ines Pinto da Costa, a Portugal-based lawyer at PLMJ, pitched the business to five of the island’s specialists in offshore wealth management and explained that an unnamed “client” wanted a new helper to manage a Mauritius company, East Star Ltd. The emails did not mention dos Santos but said “the ultimate beneficial owner is a PEP” — an acronym for a “politically exposed person,” an individual who poses a potential corruption risk given his or her connections to political or government officials.

Mauritius was central to plans to reorganize dos Santos’ Mozambique cell phone operation, Mstar. Dos Santos and other investors chose Mauritius as “a strategic approach to the development of new opportunities in the African Continent,” according to a PowerPoint presentation.

Internally, dos Santos’ advisers feared that Mauritius operators would balk at her political connections and complex business arrangements. One called the Mauritius plans a “headache.” Emails from Luanda Leaks show that the advisers had no cause for worry.

Tri Pro, a small boutique management company in Cybercity, Mauritius, was quick to respond.

“This process shall not only be costly but also difficult” with local regulators, wrote Tri Pro employee Marc Ah Ching. Despite possible challenges, Tri Pro offered to create and manage the Mauritius company for little more than $2,000.

The Mauritius office of Appleby, one of the world’s largest and most prestigious offshore law firms, also responded enthusiastically. Appleby was the subject of ICIJ’s 2017 Paradise Papers investigation that revealed offshore activities and interests of more than 120 politicians and world leaders and tax engineering by iconic corporations, including Apple and Nike.

Like Tri Pro, Appleby said that the situation looked “complicated,” according to an email sent by its managing partner in Mauritius, Malcolm Moller. Appleby, too, offered its services.

Internal emails show that dos Santos’ advisers initially decided on a third offshore specialist, Orangefield, and revealed dos Santos’ role. Advisers for the Angolan billionaire favored Orangefield and appeared satisfied the firm would be easier to work with, according to emails.

“It is crucial that we understand which of the two service providers seems more committed to working with East Star and . . . who can bring a case to us of simpler KYC,” wrote Antonio Rodrigues, a central dos Santos administrator at the management firm, Fidequity. KYC refers to “know your customer” rules that require companies like Orangefield to verify that a future client is not involved in bribery, corruption or other wrongdoing.

Yet, after months of delay, dos Santos’ advisers went full circle and settled on Tri Pro. Before inking the deal, Portuguese lawyers reminded Tri Pro that “the Client” — a reference to dos Santos — was politically well-connected and the deal was “a very sensitive matter.”

Orangefield, which is now owned by Hong Kong-based Vistra, and Appleby told ICIJ that dos Santos and her companies had never been clients. “Vistra is committed to complying with local and international regulations, holding itself to the highest ethical and compliance standards,” the company said.

Tri Pro told ICIJ that it could not disclose “confidential information.” It declined to comment on what background checks, if any, it conducted on dos Santos.

Project Rhino

Over dinner in London in mid-autumn 2014, dos Santos and Dokolo gushed before industry bigwigs about their plans for a new Angolan brewery.

“Sindika and I were very pleased to meet you,” dos Santos wrote on Oct. 7 to Heineken CEO, Jean-François van Boxmeer and then head of Africa operations, Siep Hiemstra. “We are convinced, that a common vision exists,” she wrote.

Documents from Luanda Leaks show that dos Santos and Dokolo hoped to team up with Heineken and, via Mauritius and Malta, avoid paying taxes to Angola, one of the world’s poorest countries. The project was codenamed Project Rhino.

One week after dinner, Dokolo told Angola’s ministers of commerce and industry that he and his wife’s company, Sodiba, had reached an agreement with Heineken.

Plans moved quickly. By the end of the month, PwC employees in Portugal and Angola drafted a tax memo for Sodiba as it explored selling 25% of its shares to Heineken.

PwC proposed two scenarios, according to the plan. In the first, dos Santos would sell Sodiba shares directly to Heineken. In the second, dos Santos would sell her stake to a shell company in Malta, “MaltaCo2.” Heineken would then buy the shell company.

“There is a risk of the Angolan Tax Authorities may challenge the sale price from Sodiba SA to MaltaCo2 if they become aware of the subsequent sale of MaltaCo2 to Heineken,” PwC wrote, referring to its second suggestion. “However, the risk of detection is low,” PwC wrote.

Rita de la Feria, tax law professor at the University of Leeds, said that PwC’s advice could have helped Sodiba avoid taxes by shifting profits out of Angola.

De la Feria said she had not seen language used by PwC about “low” risks of detection since 2002, when a U.K. court ruled that another consultancy firm, KPMG, had helped a slot machine business avoid $6.3 million in taxes. That case, de la Feria said, “showed a level of arrogance that consultancy companies had at that time in regard to tax avoidance in that they wrote it all down.”

“Essentially no one says this anymore because it’s basically proof that you are aware this can be challenged as tax avoidance.”

PwC continued working for dos Santos’ Sodiba until 2017, proposing a strategy to help reduce Sodiba’s consumption taxes (estimated cost: $37,500) and offering a market analysis on Angolan beer (cost: $25,000).

In January, following the publication of Luanda Leaks, PwC announced it would end its business with dos Santos and Dokolo and had opened an inquiry into how and why it worked for the couple.

PwC declined to respond to questions about its work on Project Rhino and referred ICIJ to previous statements in which it said it has “taken action to terminate any ongoing work” for entities controlled by members of the dos Santos family.

Heineken told ICIJ media partner Süddeutsche Zeitung that it “did not conclude a deal at the time” with Sodiba.

The brewery opened in January 2017. In December 2019, after ICIJ and media partners contacted dos Santos with questions about her business deals, a court in Angola froze her assets, alleging that she, Dokolo and a Portuguese adviser caused the state losses of more than $1 billion. Dos Santos denies wrongdoing. In responses sent to ICIJ by London lawyers before the publication of Luanda Leaks, dos Santos denied using offshore companies to avoid tax in Angola.

The Angolan asset freeze included the couples’ Sodiba stake. This month, the company announced that, without dos Santos and Dokolo’s financial support, it risks bankruptcy.