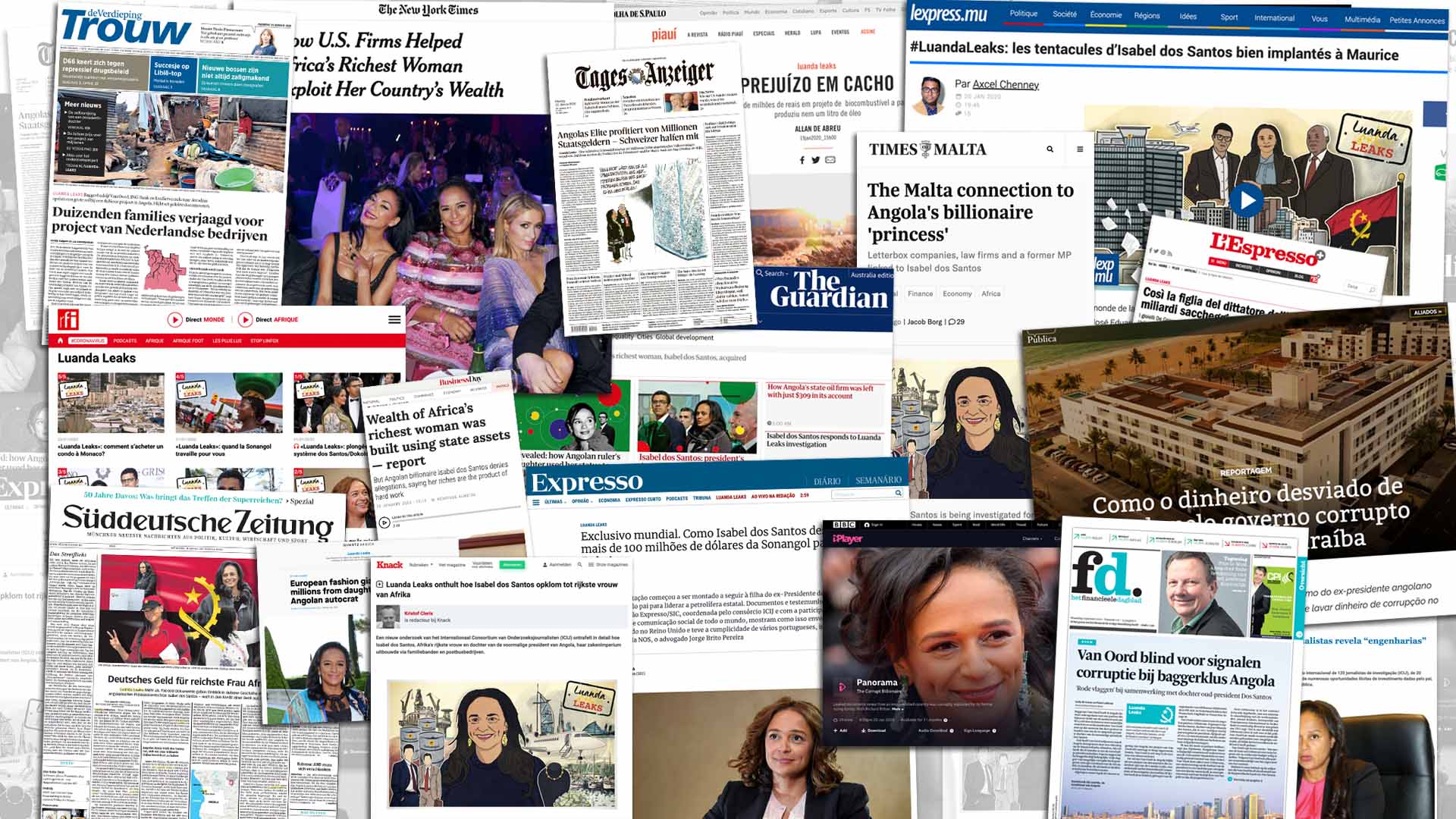

The Luanda Leaks investigation revealed how Isabel dos Santos, Africa’s richest woman and daughter of the former Angolan president, made her fortune. But how did the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists come into the 700,000 leaked files that helped tell the story – and how did the collaboration of 36 media partners from around the world come together?

United States-based media partner PBS Frontline interviewed ICIJ’s project manager Fergus Shiel, about how ICIJ made sense of hundreds of thousands of documents, built a reporting collaboration and continues its mission to “shine a light in dark places, to uncover broken systems.” U.S.-based readers can watch Frontline’s Luanda Leaks documentary here.

This interview was originally published by PBS Frontline and has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Can you talk about how ICIJ came to possess the Luanda Leaks?

The investigation is largely based on more than 715,000 documents that provide a window into the inner workings of dos Santos’ companies. An organization called PPLAAF, the Platform to Protect Whistleblowers in Africa… obtained the files from a whistleblower and shared them with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. That’s how we received them.

How do you even begin to make sense of so many documents and start connecting the dots to find the larger story?

The first thing is to look at what we have, and so the documents include confidential emails, contracts, spreadsheets, ledgers, audits, incorporation papers, organizational charts, lists of clients with overdue payments for jewels, board of directors meeting minutes and videos, bank loan and other loan agreements. …[E]ssentially, they’re business documents.

What we do as a first step is we gather them, and then we index and share them all in a confidential database, which is called Datashare. And then we make those documents accessible across the world. That first step is really critical, making sense of what we have. In this instance, we shared them with more than 120 journalists from 36 other media organizations, and we used a second invitation-only platform to discuss and dissect them.

We don’t rely simply on the documents, obviously. In this instance, as with others, we do a whole lot of work around them. In this case, ICIJ and its partners — including FRONTLINE — traveled to Angola, interviewed dozens of people, including former dos Santos employees and financial experts. We received additional documents, not simply the trove that PPLAAF gave us, but along the way we acquired more, including invoices from the Angolan state oil production company, Sonangol and also internal documents from Angolan state’s diamond company, which is called Sodiam.

How did the ICIJ and its reporting partners approach the Angolan government?

To begin with, the Angolan authorities were very wary of ICIJ and its partners, so much so that it was even difficult for some reporters to travel to Angola. For several months, we didn’t know if anyone would be let in. Eventually we were let in. And then, over many months, we built contacts in Luanda that ultimately yielded information that has proven critical to underpinning some of our key findings. But it was a really painstaking, difficult process where there was a large degree of mistrust on behalf of the Angolan government, which we worked to overcome.

How does this fit in with the ICIJ’s broader work — especially the ones everyone’s heard of: the Panama Papers and the Paradise Papers?

The famous American reporter Walter Lippmann said a hundred years ago, “There can be no liberty for a community which lacks the information by which to detect lies.” ICIJ’s mission essentially is to shine a light in dark places, to uncover broken systems, and to do so with the most rigorous standards of evidence. Our intent is to toss aside preconceptions, to set our sights on conducting an impartial and thorough investigation of the facts as is humanly possible. Luanda Leaks falls squarely within our mission.

Above everything, what the Panama and Paradise Papers taught us was that meticulous, thorough, brave investigation could best be achieved in collaboration with others. As you mentioned the Panama Papers, that was something like more than 11 million documents. And in this case, Luanda Leaks, 715,000, which is no mean number. So we use collaboration as an antidote to complexity, an antidote to timidity, because it takes a certain amount of bravery to take on so many documents, and it also takes a special amount of bravery to take on some of the most wealthy and powerful people in the world. We find that individually we may not be brave, but collectively we can be.

And it’s also an antidote to the confusion of many languages — because by harnessing reporters around the world we overcome problems of how to speak Portuguese, for instance — and many legal systems, and to the tyranny of distance when covering stories.

Getting at the truth is hard. Being heard even if you do get at it, is harder still. Collaboration is ICIJ’s recipe for both of those.

What sort of lessons did ICIJ learn with working on the Panama Papers and Paradise Papers and all the other investigations that you’ve done that you were able to bring to this one?

Each investigation is unique… but the foundation to all of them is the same. It goes back to the model we’ve built from the Panama Papers and on, which is radical sharing. We invite those whose trust we’ve built through previous, often smaller, collaborations, to join us again and we also try to harness the expertise of people around the world. And then we do what very few others do — we share with them all our secrets, and we tell them, “Here’s what we’ve got, make of it what you will.” And we help them to do the best stories that they can, not just our stories but their stories. We invest as much in their stories as we do in ours.

Our approach is transnational, and multilingual, totally transparent and generous to a fault in sharing credit. Our aim is not to take the credit for ourselves, our aim is for the story to be as good as it can be. …[H]aving a reporter in Angola looking at an Angolan story makes sense, having a reporter in France looking at a French story makes sense, having a reporter in Portugal, who can speak Portuguese, the language that is used in Angola, makes sense because it bypasses so many complexities. On top of that, we also encourage reporters to gather around themes that interest them because we find that enthusiasm is a great lubricant when it comes to investigations. If people are genuinely enthused about what they’re looking at, then they do more work and better work.

There are only two rules — we agree to share, and we publish on the same day.

Could you talk about how ICIJ works on these massive collaborative projects – what’s the process through which you find reporting partners, how does the reporting process go?

When we received the documents, the critical breakthrough for me was when I rang Micael Pereira from Expresso, which is a Lisbon paper. I said to him, “Would you be interested in an investigation into Isabel dos Santos and Angola?” And he immediately, and without hesitation, said, “Yes, because this is what we should be doing. This is the most important thing I can do. This is a really important story for Africa. This is a really important story for some of the poorest people on the planet.” If Micael had not come on, we would have been in real trouble, because we needed — as a vanguard if you like — somebody who knew Angola and somebody who spoke Portuguese.

Then what we were able to do is go back to the secrecy jurisdictions and say, “Okay, the dos Santos empire has many companies in Malta.” So then we rang the [Times of Malta’s] Jacob Borg who we’d worked with before and asked, “Jacob, would you be interested?” And he said yes. …And that’s how we built it. It’s like a jigsaw puzzle. We begin with one key piece and then we build the puzzle out in terms of reporting strength. And as we build, we try to make sure that we build into the team people that know about specific areas. We build expertise. We build geographical spread. And we build using people that we trust and we’ve worked with before.

What do you hope people understand or take away from this project?

There are three things — the first is that the truth matters, the second that Africa matters and the third that journalism matters.

—

This interview was originally published by PBS Frontline and has been reproduced with permission.