Cape Verde will close banks that serve only foreign customers, including one partly owned by Angolan billionaire Isabel dos Santos, following Luanda Leaks revelations, the country’s finance minister has pledged.

Olavo Correia, who is also the Macaronesian nation’s deputy prime minister, said new laws to shutter so-called “offshore” banks that provide services to non-resident customers would apply to four banks, including Banco Bic Cabo Verde. Offshore banks have one year to start servicing local residents or face closure.

Dos Santos, who was the subject of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists-led Luanda Leaks investigation, holds 42.5% of the bank.

On Feb. 21, Cape Verde’s parliament unanimously agreed to shutter so-called “offshore” banks that provide services to customers who do not live in the country. The law will apply to four banks, including Banco Bic Cabo Verde.

Correia told journalist Margarida Fontes that the investigation helped build vital support for the new laws.

“Luanda Leaks made the measure more understandable, broadened the consensus in society and facilitated the approval process unanimously and without any social noise,” Correia said.

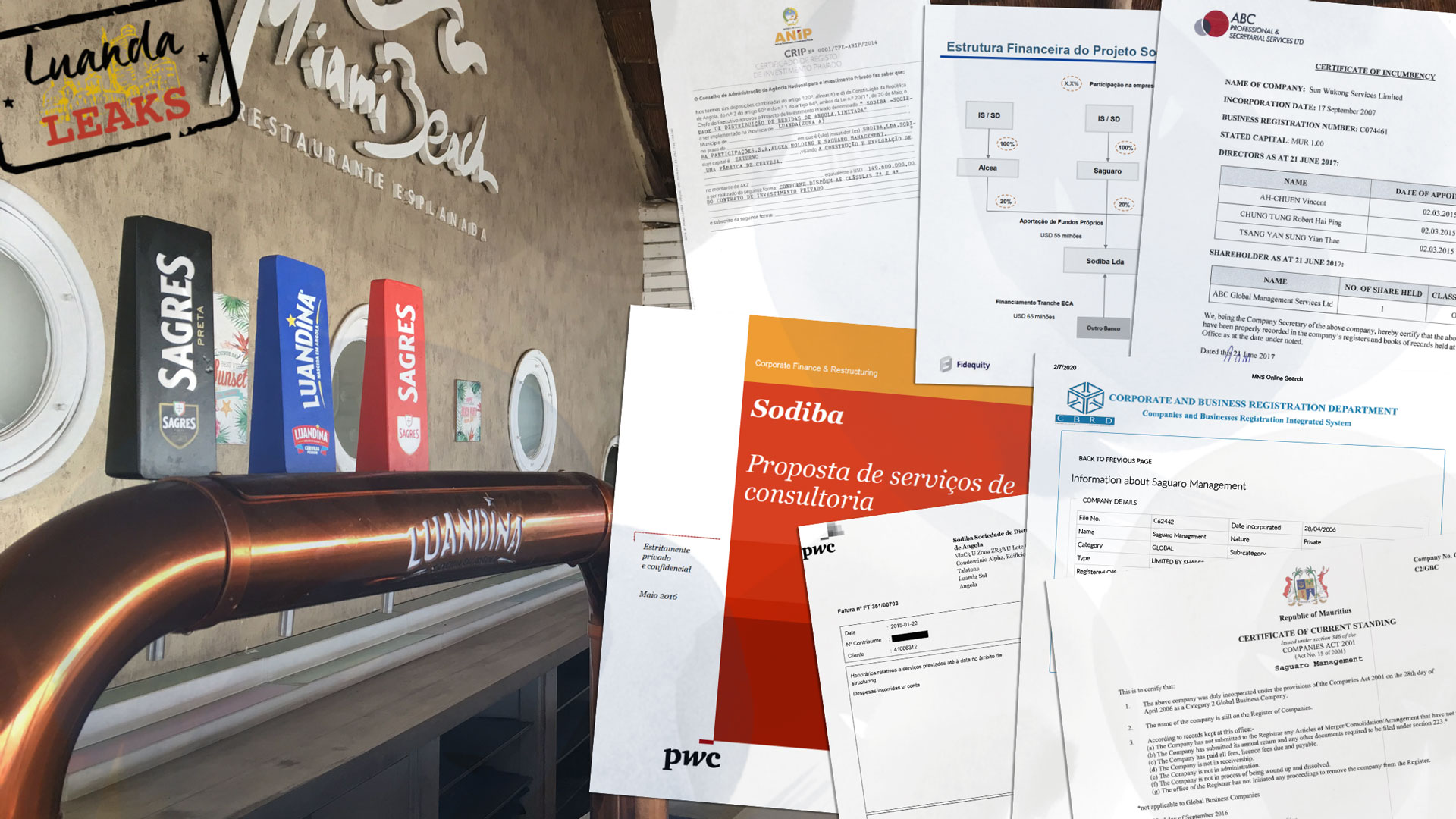

The Luanda Leaks investigation is based on a trove of financial and business records obtained by the Platform to Protect Whistleblowers in Africa and shared with ICIJ.

The investigation revealed how dos Santos, assisted by lawyers, accountants and advisers, amassed her fortune by exploiting shell companies, insider deals and her relationship with her father and Angolan president, Jose Eduardo dos Santos. Isabel dos Santos bought a stake in Banco Bic Cabo Verde in 2013.

At that time, Cape Verde’s regulations required offshore banks to be 15% owned by a bank in a country within the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development.

Fontes and London-based Finance Uncovered revealed that dos Santos’ co-investors in Banco Bic Cabo Verde pressured local regulators in 2013 to waive the requirement and grant it a banking licence.

Finance Uncovered also identified how her Cape Verde bank became an increasingly important part of dos Santos’ payments system as concern grew among other financial institutions over her politically exposed status.

It reported that between 2016 and 2017 dos Santos companies invoiced more than $35 million to accounts at her Cape Verdean bank under contracts signed in Angola.

In May 2019, an international review of Cape Verde found “insufficient application” of anti-money laundering laws and a “total lack of supervision” in certain high-risk sectors. The country’s financial industry had “inadequate understanding” of money laundering and terrorism financing, the review found.

Cape Verde subsequently closed certain loopholes and, in February, European Union finance ministers removed the country from a blacklist of tax havens.

“Cape Verde’s economic growth is based on the fact that it’s a very remote archipelago that has been discovered as a new place to do business, like classic Caribbean island tax havens, with a mix of legitimate and illicit money,” said Thierry Vircoulon, a researcher at the French Institute of International Relations (IFRI) who studies money laundering in Cape Verde.

“Passing legislation is one thing,” Vircoulon said. “Implementing it is another.”