Walking past bay windows that overlook the private women-only beach, guests at the Six Senses Spa at Oman’s Al Bustan Palace can pause for an invigorating face scrub made from local frankincense and clove.

For well-heeled tourists visiting the sultanate, the spa, part of the Ritz Carlton Hotel complex, provides an opulent respite from scorching summer temperatures rising above 120 degrees Fahrenheit.

Less happy with the spa experience? Oman’s Secretariat General for Taxation.

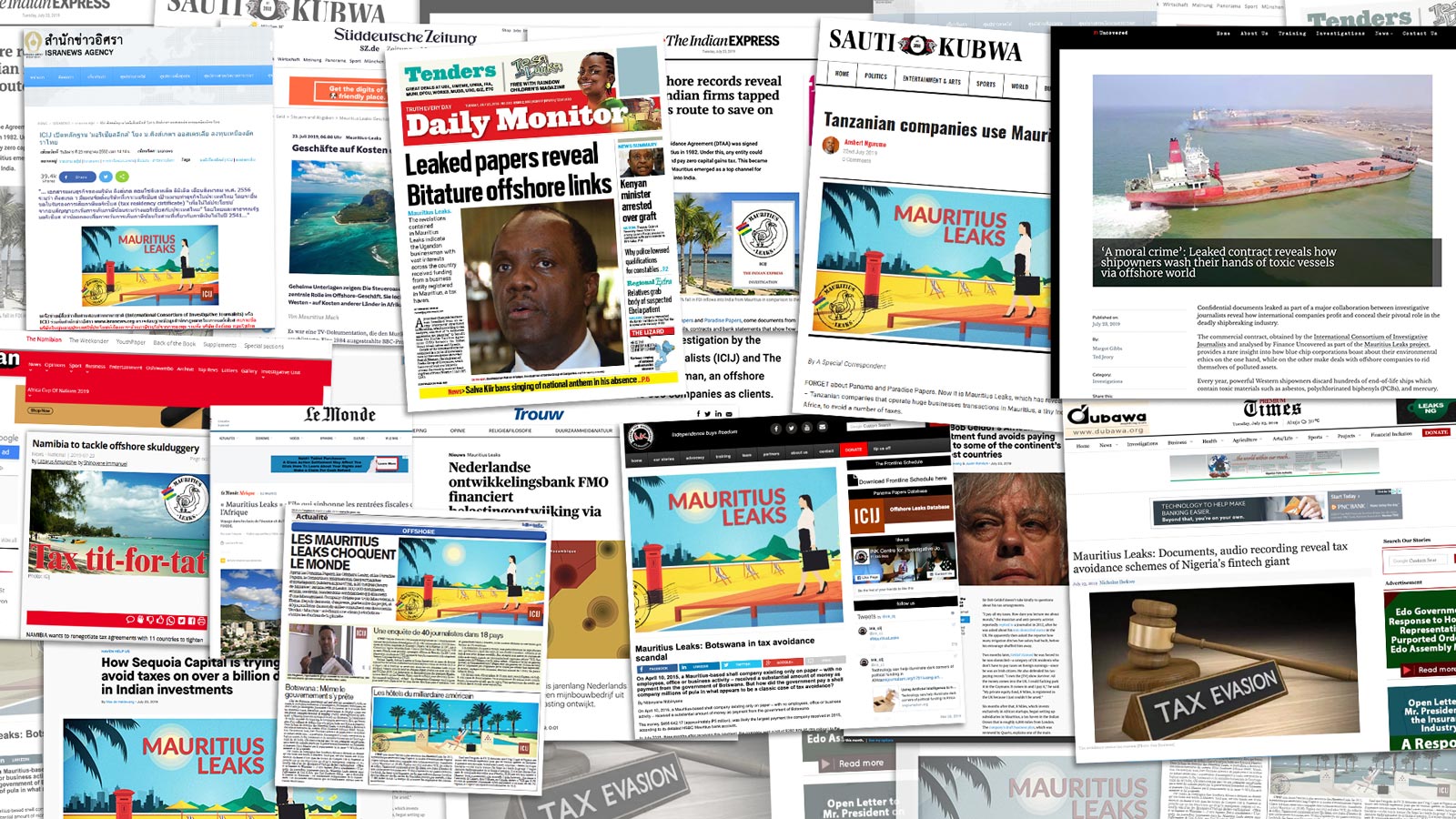

For years, the spa’s former U.S. owner conducted its affairs through offshore companies and bank accounts that may have allowed it to avoid paying taxes in Oman, one of the poorest Persian Gulf states, while funneling revenue thousands of miles away to Mauritius, according to documents found in Mauritius Leaks, a trove of more than 200,000 files leaked to the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists.

Helped by Oman’s most prestigious law firm, the spa exploited offshore vehicles for everything from management fees to the right to use the Six Senses logo on toothbrushes.

Worldwide, Six Senses’ owners until earlier this year, Connecticut-based private equity firm Pegasus Capital Advisors, routed payments to and from 53 spas and hotels on every continent except Antarctica, according to documents from lawyers at Conyers Dill & Pearman in Mauritius.

The documents regarding a single spa and hotel chain open a window onto the financial flows that enrich and sustain the $171 billion luxury hotel industry, whose tax practices have been under scrutiny for years. In 2012, BBC Panorama reported that London’s Ritz hotel hadn’t paid corporation taxes for 17 years. Barcelo Hotel Group reported losses in Mexico that could allow it to pay no taxes for years, University of Calgary researcher Linda Ambrosie found.

Ambrosie, an accountant and author of “Sun and Sea Tourism: Fantasy and Finance of the All-Inclusive Industry,” says hotels regularly use tax havens to pay less to governments in cash-poor countries, which are often desperate for local employment and tourist dollars, pesos and rials.

“This so-called ‘clean’ industry is just as dirty as oil and gas,” Ambrosie told ICIJ. “Where these companies are operating is exactly where the taxes are needed.”

Project Sun

In 2012, Pegasus Capital Advisors, run by wealthy financier Craig Cogut, bought Six Senses in a deal codenamed “Project Sun,” according to documents from ICIJ’s Mauritius Leaks investigation.

Six Senses’ wellness and sustainability mantra fit the public ethos of Cogut’s $1.5 billion firm, which invests in high-end pet food (“The Proof is in the Poop”), recycling and LED lighting and other businesses.

As part of the Six Senses purchase, Pegasus took over contracts for existing resorts and spas, including some that exist on properties owned or managed by other companies. Pegasus also bought the Six Senses’ trademarks: the pyramid logo that bedecks slippers, dressing gowns, toothbrushes and brochures.

In May 2012, with the help of the Conyers law firm, Pegasus created a new company in Mauritius, Sustainable Luxury Mauritius Ltd. Cogut was listed as the company’s owner, according to documents from Mauritius Leaks.

Pegasus transferred intellectual property to the Mauritius company. Spas from countries such as Thailand, Sri Lanka and Portugal paid Sustainable Luxury to use the logo, according to contracts.

Hotel companies regularly own intellectual property instead of bricks and mortar. U.S. President Donald J. Trump, for example, received income from the use of his name on the Trump Ocean Club International Hotel and Tower in Panama City, which he does not own.

The arrangement allows hotel and spa operators to make money from branding without the burden of owning and operating a sprawling, physical complex. Yet experts say the arrangement opens the door to tax avoidance.

A shell company can charge fees for the use of a hotel logo, for example, to a related business in a high tax location where a hotel is based. That business pays the shell company to use the logo, allowing the operator in a higher taxing country to lower its taxable income and send money to the company in the tax haven — often untaxed.

“They’re taking the cream right off the top,” Ambrosie said of the hotel industry in general. “It is extremely difficult for tax authorities, especially in countries that aren’t as sophisticated as the U.S., to show that the logo isn’t worth what they claim it is.”

Pegsus and Cogut did not respond to requests for comment.

Pegasus also sought to benefit from another Mauritius tax-avoidance feature: its battery of so-called double taxation treaties.

A few weeks before creating the Mauritius company, Conyers and Pegasus prepared a business plan that said the newly minted firm would require “tax residency certificates” to benefit from treaties signed between Mauritius and other countries where the hotels are located. Oman appeared first on a list of five countries for which Sustainable Luxury sought tax benefits.

Once a diplomatic afterthought, taxation treaties have grown to become central pillars of contemporary global business.

While the treaties are widely promoted as encouraging foreign investment through guarantees that businesses will only be taxed once, critics counter that they limit poorer countries’ rights to collect revenue and offer little in return. Under some treaties signed with Mauritius, for example, countries have agreed to reduce or abolish taxes on cross-border payments made to a company on the island. Tax authorities in developing countries claim that treaties signed with low-tax Mauritius can allow a company to avoid taxes by claiming to be “based” in Mauritius when, in reality, the company there exists only on paper. Sustainable Luxury Mauritius had no employees or an office, according to a 2015 tax return, which listed “0” for the value of expenses for wages, electricity and rent.

“I would say that a high proportion of international transactions are structured the way they are because of a tax treaty,” said Sunita Jogarajan, associate professor at the University of Melbourne Law School who has explored the origins of tax treaties.

“Every government service comes down to tax,” Jogarajan said. “So for me, it’s a question of ‘How can you not care about tax treaties?’”

Cash-strapped sultanate

On the toe of the Arabian Peninsula, Oman is the poor relation in a family of Gulf nations that drip with oil, finery and millionaires.

It has a low corporate tax rate and, despite the existence of oil and gas, struggles to create jobs, pay civil servants and upgrade public housing. Oman receives taxes well below what they should based on corporate profits made in the Sultanate, economists say. Last December, Fitch Ratings downgraded the country’s debt to junk status.

Financial publications have taken to calling Oman the “cash-strapped sultanate.”

In 2011, during the Arab Spring, thousands of Omanis took to the streets, burning tires and throwing rocks to protest corruption, rising living costs and a muzzled media. At least two were killed in clashes with security forces.

Oman increased some taxes in 2017, but, slumping oil prices pushed Oman’s leaders to slash health, education and social spending by up to 5%.

To rebalance the economy away from oil, the sultanate has turned to tourism — Oman’s “Plan B,” some call it. In the past decade, Oman more than doubled the number of tourists visiting the country to 2.6 million.

These are tourists who aren’t likely to question Oman’s model … They are there to spend money. – Marc Valeri

And not just any kind of tourism. The growing industry is “reserved to wealthy and easily controllable elites of the West,” said Marc Valeri, director of the University of Exeter’s Centre for Gulf Studies.

Omani leaders had feared that low-end tourism could create political problems, Valeri said. “These are tourists who aren’t likely to question Oman’s model. They aren’t there as backpackers who will go into small villages and interact with Omanis and their daily life. They are there to spend money.”

The Six Senses System

Oman’s Al Bustan Hotel spa is one of Six Senses’ crown jewels. “Five-star hotels and luxury tourism operators like Al-Bustan and Six Senses spa are absolutely critical to Oman’s aspirations as a tourism hub,” Valeri said.

Over ginger tea and almonds at Al Bustan, spa clients consult promotional brochures that read: “It starts from within. From an innate belief in doing good.”

Al Bustan, which means “the garden” in Arabic, is part of a global empire.

View this post on Instagram

Release your inner Pagan #sunworship @sixsenseszilpasyon @elizabethhurleybeach

Hollywood star Angelina Jolie took her children to Six Senses Vietnam; British actress and model Elizabeth Hurley pranced on Six Senses beaches in the Seychelles; and pop music heartthrob Nick Jonas and actress Priyanka Chopra honeymooned in Oman’s Zighy Bay. That five-star Omani hotel and spa, in a remote northern nook, allows guests to arrive via paraglider, contributing to an experience that online reviewers describe as a mix of James Bond and “Mad Max-meets-The-Flintstones.”

When the Connecticut-based private equity company bought Six Senses, it transferred management, licensing and marketing contracts signed by the brand’s former owners to its new offshore company, Sustainable Luxury. Almost overnight, Sustainable Luxury earned the right to lucrative income from spa and hotel management deals, according to records.

Under a revised contract between Sustainable Luxury, the government of Oman (which owns Al Bustan Palace) and the Ritz Carlton Hotel Company (which took over management of the hotel from InterContinental Hotels in 2011), the Mauritius company received 3% of the spa’s revenue each month for the right to use Six Senses trademarks, including the pyramid logo that adorns uniforms and products and the “Six Senses System,” which included the spa procedures.

Helping Sustainable Luxury in Oman with its offshore deals was the celebrated law firm Al Busaidy, Mansoor Jamal & Co., according to bank transfers, emails and letters. Al Busaidy did not respond to ICIJ’s questions.

Experts said that, without the tax treaty with Mauritius, Oman could have levied taxes of 10% on some payments. When Sustainable Luxury chose Mauritius, however, Oman lost out: for certain services, the treaty between the two countries prevents Oman from collecting taxes on fees paid to the Mauritius company.

Six Senses’ second Omani operation, at Zighy Bay, also made payments to the Mauritius company under marketing, licensing, sales and management agreements, according to documents.

Sustainable Luxury signed agreements for managing spas, making sales and signing marketing deals in Portugal, China, France, the Maldives and elsewhere, according to documents. One draft document shows the Mauritius company acquired 184 management and other fee-making agreements in 34 countries.

The company’s Mauritius 2014 financial statement reveals Sustainable Luxury reported no tax liability on revenue of $6.6 million, largely from management service fees. “As at 31 December 2014 the Company had a tax liability of USD Nil,” the statement said.

“They are definitely involved in aggressive tax planning,” said Ambrosie, the accountant and author.

In February, Six Senses changed hands again when InterContinental Hotels Group paid Pegasus $300 million. In its announcement of the cash purchase, InterContinental Hotels said that the deal includes “all of Six Senses’ brands and operating companies and does not include any real estate assets.”

Asked whether InterContinental Hotels Group will keep the agreements and tax benefits of the Mauritius shell company Sustainable Luxury, the hotel chain directed ICIJ to a statement on its website that touts the company’s commitment to “doing business responsibly.”

The InterContinental Hotels Group is already well placed on the island; the hotel chain has a subsidiary there. You can find its office in the adjoining tower of the building where Sustainable Luxury had its mailbox.