For months, Gu Kailai worried about a secret that threatened to upend her comfortable life and stop her husband’s climb to the top rungs of China’s political leadership. So she took action.

In a hotel room in the southern Chinese megacity of Chongqing, she mixed tea and rat poison in a small container as Neil Heywood, a British business associate, lay drunken and dazed on the hotel bed.

Then she dripped the mixture into Heywood’s mouth.

Hotel staff found his body two days later.

Gu eventually confessed to the 2011 crime. She had been driven to murder, she said, by Heywood’s threats to expose a dark secret: millions of dollars in real estate held in an offshore account on the other side of the world.

If Heywood revealed that she had used a company in the British Virgin Islands to hide her ownership in a villa in the south of France, she figured, the scandal would jeopardize the accession of her husband, Bo Xilai, to the Politburo Standing Committee, a body of fewer than 10 men that stands at the apex of political power in China.

Just over two weeks after the murder — in a previously unknown postscript — the ownership structure of Gu’s offshore company suddenly changed. Her shares in the company were transferred to another business associate, perhaps in an effort to further obscure her ties to the company or to make it easier for the trusted associate to act swiftly as events unfolded, a trove of secret records shows.

In the end, nothing could hide Gu’s secrets. Her pursuit of offshore anonymity ended in death for Heywood and prison for her and her husband — and added more fuel to longstanding concerns about how members of China’s elite use tax-haven hideaways to conceal their wealth.

The leaked documents that provide fresh details about Gu’s overseas dealings also reveal a wealth of new information about the offshore holdings of the families of other powerful Chinese.

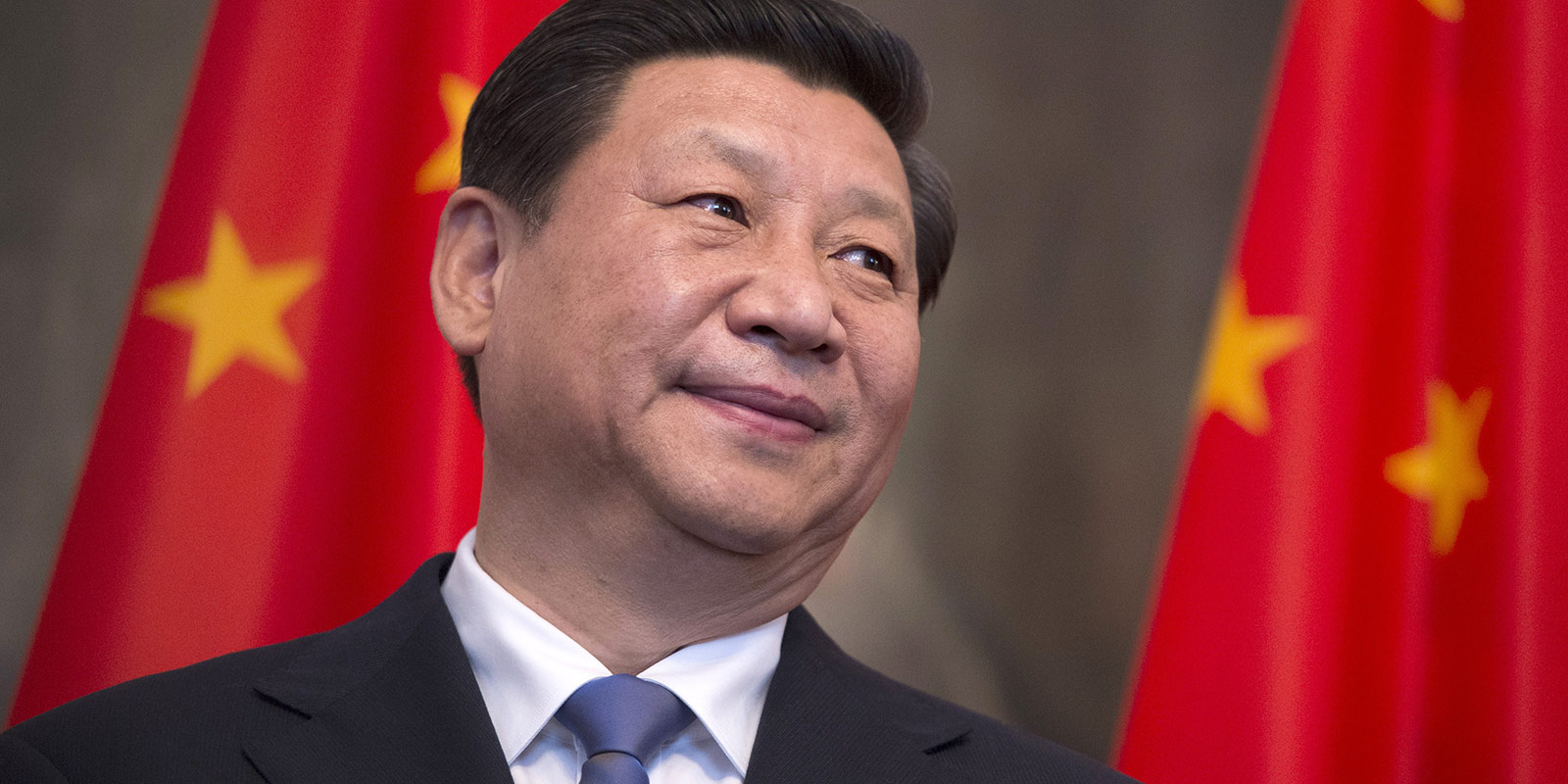

The documents reveal that Xi Jinping, China’s “Chairman of Everything,” — his titles include president, Communist Party chief and military chief — has a brother-in-law who has had companies in tax havens. Relatives of at least seven other men who have served on the tiny Standing Committee — including two members currently serving with Xi — also have offshore holdings, the records show.

One of these relatives is a grandson-in-law of the late Chairman Mao Zedong, the founding father of the People’s Republic of China.

It is no secret that many of the children and grandchildren of China’s revolutionary heroes have found success in the business world. China has the world’s second largest economy and has hundreds of billionaires. But the extent to which some of the country’s most politically connected have tapped offshore networks to keep their assets hidden from the public eye is not well known. And the mechanics of how they do it is little understood.

The cache of documents was obtained by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung and other media partners. The records — more than 11 million documents in all — come from the files of Mossack Fonseca, a Panamanian law firm that sells shell companies and other offshore structures to customers who want to keep their finances private.

Among the law firm’s high-flying Chinese customers is Deng Jiagui, the brother in law of China’s paramount leader Xi Jinping, who has made anti-corruption a hallmark of his rule. Deng Jiagui acquired one offshore firm via Mossack Fonseca in 2004 and two more in 2009.

The companies were called Supreme Victory Enterprises Ltd., Best Effect Enterprises Ltd. and Wealth Ming International Ltd. It is unclear what the companies were used for. Supreme Victory was dissolved in 2007, and the other two companies had become dormant by the time Xi became Communist Party chief in 2012. Deng Jiagui did not respond to ICIJ’s requests for comment.

Another prominent client is the daughter of Li Peng, China’s premier from 1987 to 1998. Li is best known internationally for overseeing the bloody military crackdown on the 1989 Tiananmen Square pro-democracy protests.

His daughter, Li Xiaolin, and her husband own Cofic Investments, a British Virgin Islands company incorporated in 1994. In internal emails, Li’s lawyers say the firm’s funds came from helping facilitate the export of industrial equipment from Europe to China. The files show that ownership was cloaked for many years by use of so-called bearer shares, which are registered without names — if the bearer certificates for a company are in your hands, you own the company. Bearer shares have long been considered a vehicle for money laundering and other wrongdoing, and have been gradually disappearing worldwide as jurisdictions toughen regulations aimed at stopping the flow of dirty money.

The new generation of so-called red nobility seems to have learned about the offshore world at a young age. The granddaughter of Jia Qinglin, who served as the No. 4 member of the Politburo Standing Committee until 2012, has offshore assets. Jasmine Li Zidan became the owner of an offshore company called Harvest Sun Trading Ltd. in 2010 — when she was a freshman at Stanford University.

Since then, Jasmine Li has built a surprisingly large business for someone still in her 20s: her two British Virgin Islands shell entities were used to set up two companies in Beijing with total registered capital of $300,000. By having the two BVI companies own Li’s shares in the Beijing companies, she was able to keep her family name off the public registration documents.

The five other current and former Standing Committee members whose relatives are connected to offshore dealings are:

Zhang Gaoli, a current Standing Committee member, has a son-in-law named Lee Shing Put, who was a shareholder of three companies incorporated in the British Virgin Islands: Zennon Capital Management, Sino Reliance Networks Corporation and Glory Top Investments Ltd.

Liu Yunshan, a current Politburo Standing Committee member, has a daughter-in-law named Jia Liqing who was the director and shareholder of Ultra Time Investments Ltd., a company incorporated in the British Virgin Islands in 2009.

Zeng Qinghong, who was vice president of China from 2002 to 2007, has a brother named Zeng Qinghuai, who was the director of a company, China Cultural Exchange Association Ltd., that was incorporated first in Niue and then re-domiciled in 2006 in Samoa.

The late Hu Yaobang, who served as head of the Chinese Communist Party from 1982 to 1987, has a son named Hu Dehua who was shareholder, director and beneficial owner of Fortalent International Holdings Ltd., a company incorporated in the British Virgin Islands in 2003. Hu Dehua registered the company using his home address — the traditional courtyard home where his father lived while party chief.

Mao Zedong, who led Communist China from 1949 to his death in 1976, has a grandson-in-law who incorporated Keen Best International Limited in the British Virgin Islands in 2011. Chen Dongsheng is the head of a life insurance company and an art auction house and was the sole director and shareholder of Keen Best.

China’s Foreign Ministry did not respond to a faxed request for comment by ICIJ. Asked whether China plans to investigate any of the China-related companies or holdings revealed in the leaked documents, ministry spokesman Hong Lei told a regular press briefing in Beijing on Tuesday that he had no comment on the “groundless accusations.”

Communism meets capitalism

The leaked records shine light on how some Chinese political elites use the offshore world to keep their finances discrete.

Not all offshore dealings are illegal, but incorporations in the BVI and elsewhere can be used to obscure financial relationships between political elites and wealthy patrons, to hide assets, evade tax and enable anonymous stock purchases. They also allow high-profile individuals to set up an onshore business in the name of their offshore shell company without anyone knowing it's theirs. These are but a few of the techniques greasing the wheels of modern Chinese capitalism with communist characteristics.

Along with politically connected princelings, Mossack Fonseca’s customers from China include the super wealthy such as Shen Guojun, who founded the Chinese shopping mall chain Intime. Shen was a shareholder, together with the kung fu star Jackie Chan and others, of a company called Dragon Stream Limited that was incorporated in the British Virgin Islands in 2008.

Another billionaire, Kelly Zong Fuli, the daughter of billionaire soft drink magnate Zong Qinghou, acquired a BVI company called Purple Mystery Investments with help from Mossack Fonseca in February 2015. Correspondence shows the purpose of the company was “investment in China.”

Shen Guojun, Jackie Chan and Kelly Zong Fuli did not respond to ICIJ’s requests for comment.

The Panamanian law firm — considered one of the top five incorporators of offshore companies in the world — set up Mossack Fonseca Secretaries Limited in Hong Kong in August 1989 and, in its early days, operated out of an office in the Kowloon Centre in Tsim Sha Tsui, a bustling, neon-lit neighborhood known for its museums and shopping. It established its first office in mainland China in 2000. Today, according to its website, it has offices in eight mainland cities: Shenzhen, Ningbo, Qingdao, Dalian, Shanghai, Hangzhou, Nanjing and Jinan.

An analysis of the leaked records by ICIJ shows that by the end of 2015 Mossack Fonseca was collecting fees for more than 16,300 offshore companies incorporated through offices in Hong Kong and China. Those companies represented 29 percent of Mossack Fonseca’s active companies worldwide and made greater China the law firm’s single leading market. Its busiest office in Asia — and globally — is Hong Kong.

International rules on money laundering require middlemen like Mossack Fonseca to give extra scrutiny to government officials and their families to make sure their money was not accumulated through graft. Some clients, such as Shi Youzhen, the wife of Zong Qinghou, the Wahaha beverage company magnate, were subject to “enhanced due diligence,” including queries about the assets held by her offshore companies.

An examination of the files shows the firm signed up other Chinese clients, however, without determining whether they had family ties to top political figures.

The documents show, for example, that no one at the firm acknowledged or identified Deng Jiagui as Xi Jinping’s brother-in-law when it helped Deng incorporate offshore companies in the British Virgin Islands in 2004 and 2009.

Mossack Fonseca also appears for years to have not acknowledged or not realized the family ties of Li Xiaolin, former Chinese Premier Li Peng’s only daughter.

Mossack Fonseca didn’t object to the use of bearer shares to control the company Li Xiaolin and her husband owned, Cofic Investments, until 2009, when the British Virgin Islands introduced tougher anti-money laundering standards that forbid their use. The leaked files show the law firm didn’t dig into the backgrounds of the real shareholders of the company even as the ownership structure was transferred in 2010 from bearer shares to another secretive arrangement, a foundation in the tiny Central European principality of Lichtenstein.

By this time, Li Xiaolin had established herself in China as more than just the daughter of a famed political leader. She had become a top executive in the Chinese energy sector — earning the nickname “China’s Power Queen” — and had become a delegate to the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, an advisory body to the Chinese legislature.

Emails show that Mossack Fonseca finally learned that Li Xiaolin and her husband were the real owners of Cofic Investments in 2014, in response to a query from British Virgin Islands financial regulators.

It is not clear from the files what the query was about but even then, at least some of the law firm’s employees appear not to have made the connection that Li Xiaolin was a prominent player in Chinese politics and business.

Geneva-based lawyer Charles-Andre Junod, who was a director of Cofic Investments, declined to comment but said he has always respected relevant laws.

Li Xiaolin did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

In a letter to ICIJ, Mossack Fonseca said the firm has “duly established policies and procedures” to identify and handle cases involving politicians or people associated with them. It said the company considers those kinds of cases to be “high risk” and conducts more intense checks and periodic follow ups. “We conduct thorough due diligence on all new and prospective clients that often exceeds in stringency the existing rules and standards to which we and others are bound.”

A company worth $1

Another princeling who slipped though Mossack Fonseca’s vetting process without much attention was Jasmine Li, the granddaughter of a former Standing Committee member. Li was a Stanford student when she entered the offshore world.

There is no evidence in the leaked Mossack Fonseca documents that the law firm ever secured a copy of her photo ID even though that was supposed to be standard procedure. Had Mossack Fonseca employees checked more closely, they might have discovered a financial relationship between her and another of their customers, Zhang Yuping, the chairman and founder of Hengdeli, a Chinese luxury watch distributor.

Zhang was the sole shareholder of a British Virgin Islands company called Harvest Sun Trading Limited.

Public records show that Harvest Sun was used to buy shares in a publicly listed company in Hong Kong called China Strategic Holdings in April 2010. A few months later, in August, Harvest Sun sold some of the shares, and it then offloaded its remaining stake in September, according to filings with the Hong Kong Exchange.

In December 2010, the law firm’s records show, Zhang transferred ownership of the now empty shell company to Jasmine Li, who was a freshman at Stanford University at the time, according to her LinkedIn page.

The selling price: $1.

The Mossack Fonseca records show that Li also has a second BVI company called Xin Sheng Investments Limited. Li used Harvest Sun and Xin Sheng to set up two similarly named Beijing companies with interests in entertainment and real estate. The offshore companies acted as shields to her identity. Li did not respond to ICIJ’s request for comment.

Zhang’s lawyer, Victor Lee, confirmed via email that Harvest Sun was transferred from Zhang to Li in 2010. The lawyer said there were no assets in Harvest Sun at the time of the transfer and that Zhang considered the transfer “reasonable” because the company was “only a shell company with no assets inside.”

“Our client had no relationship with Ms. Li, who was introduced to our client by some business partners,” the lawyer wrote, without providing details. He said the transfer meant that Jasmine Li could have the company “without the need to set up another shell company herself.”

Business people in China often attempt to curry favor with top leaders by helping their spouses, children, grandchildren and other close family relatives. The nature of these symbiotic but secretive ties were laid bare during the trials of Gu Kailai and her husband Bo Xilai, who depended heavily on a deep-pocketed plastics tycoon from far northeast China called Xu Ming. As Bo said during his corruption trial in August 2013: “Xu Ming has provided a vast amount of financial assistance to my family… I have helped him achieve ‘rapid advances,’ and he helped me to look after my son.”

White gloves

For more than a decade, Gu Kailai had managed to keep her stake in her offshore company in the Caribbean secret, which in turned allowed her to keep her villa on the Mediterranean under wraps.

She and her husband, Bo, had all the ingredients of a Chinese power couple.

Gu, the daughter of a former People’s Liberation Army general, worked as a butcher’s assistant during the Cultural Revolution but went on to become a successful lawyer.

Bo, the son of one of the powerful “Eight Elders” of the Communist Party, ran the sprawling metropolis of Chongqing and, by 2011, was a leading candidate for the Politburo Standing Committee and possibly the nation’s next domestic security czar.

As her husband’s star rose, Gu acquired the six-bedroom villa in Cannes along the French Riviera. The home was bought in 2001 with funds from Xu Ming. Xu got around China’s strict capital controls by faking the purchase of a steel workshop in order to transfer the $3.2 million offshore.

The company selling the nonexistent steel workshop took a small cut and then transferred the rest to Russell Properties S.A., a British Virgin Islands company secretly co-owned by Gu and a business associate, French architect Patrick Henri Devillers. Russell Properties S.A transferred money to a company in France that purchased and managed the villa.

On paper, nothing linked Russell Properties to Gu or her powerful husband.

Gu used the Villa Fontaine St. Georges as an investment in the hope that it would generate rental income. She later testified that she hid her ownership of the company and the villa because she wanted to “minimize” her tax. And, she said, “I did not want others to know I had overseas assets.”

To manage the villa, she turned to Heywood, a family friend who exuded equal parts flash and mystery. He was known to drive around Beijing in a Jaguar with the numerals “007” in the license plate. The Guardian reported that he referred to Gu as an unforgiving “empress.”

By helping Gu, Heywood became part of a cottage industry of operatives who serve as fronts for wealthy Chinese who want to keep their overseas assets secret. These proxies — known in China as “white gloves” — often hold the real owners’ stakes in real estate and other investments.

Acting as a white glove for the corporate and Party elite has become a lucrative business in China. For Heywood, it would also turn out to be deadly.

The unraveling

Mossack Fonseca “inherited” Russell Properties S.A. as part of a batch of offshore companies that were transferred from another registered agent in mid-2011.

At the time, the company’s shares were held by IFG Trust and IFG Secretaries, proxies located in Jersey in the Channel Islands. The registers of directors and shareholders didn’t mention Devillers or Gu, and there was no obvious link to China.

Then things began to unravel.

Gu had promised Heywood, who was managing the French villa, a cut of a real estate deal in Chongqing. Heywood believed he wasn’t getting his fair share. In early 2011, Gu later testified, Heywood approached her son, Bo Guagua, to press him to ask his family for more money. Heywood threatened to reveal Gu’s ownership of the villa, Gu claimed.

According to reports of her trial, Gu and Heywood met on Nov. 13, 2011, in the Lucky Holiday Hotel in Chongqing to discuss the dispute. They had dinner, then went to his room for drinks. He drank half a bottle of Royal Salute whiskey and vomited before being dragged to his bed by a Bo family assistant named Zhang Xiaojun. Heywood asked Gu for water.

She mixed rat poison and tea in a soy sauce container and fed it to him in sips. Gu waited until she couldn’t feel Heywood’s pulse any longer, then went to her own room in the hotel and went to bed.

Little more than two weeks later, the leaked files show, Mossack Fonseca helped transfer ownership shares of Russell Properties S.A., the shell company that controlled the villa, from the IFG proxies to Patrick Henri Devillers, the French architect who had assisted Gu in setting up the company in 2000.

Devillers used the address of Gu’s former law partner in Beijing on the transfer paperwork. According to court documents, Russell Properties had initially been held 50/50 by Gu and Devillers via the two Channel Islands proxies.

It’s not clear why the transfer was made so soon after the crime or why Gu’s share was transferred to Devillers. Indeed, it seems strange that Devillers would choose to put the company in his real name and use Gu’s former business address on the paperwork, essentially leaving his and her fingerprints on the company.

By removing IFG as a middleman, Devillers was able to establish direct contact with Mossack Fonseca, giving him greater immediate control of the company.

By early 2012, Devillers was often in the news in China, Britain, France, Australia, and the United States for his links to Gu’s murder trial and Bo Xilai’s corruption scandal. Yet, according to the leaked files, for several months in early 2012, Mossack Fonseca appeared to remain oblivious to the case. During this time, Devillers emailed Mossack Fonseca to request that they allow him to transfer Russell Properties to another offshore agent called Morgan & Morgan Trust.

Then, on June 7, 2012, British Virgin Islands regulators launched an investigation into Russell Properties S.A., requesting information from Mossack Fonseca about its owners, directors and other details. Four days later, a Mossack Fonseca compliance officer alerted her colleagues in an internal email that Devillers appeared to be linked to an investigation in China.

On June 12 and 13, Mossack Fonseca emailed Devillers directly, sending him increasingly anxious notes that included links to news stories about the Bo Xilai-Gu Kailai scandal and his alleged role in it. “The articles mentioned a person with your name and nationality,” the law firm wrote. “Please advise us whether the person in question and you are the same person.” He appears not to have replied.

In its response to the British Virgin Islands authority, the law firm stated that a man named Patrick Henri Devillers was the sole shareholder and director of Russell Properties, and “our last contact regarding this company.” It made no mention of the company’s apparent links to the scandal unfolding in China though it promised to dig deeper and provide more information later about Devillers and the company.

Home for sale

Devillers now lives in Cambodia. His testimony was used in both the trials of Gu and Bo but he was never charged with any crime. He did not answer ICIJ’s repeated requests for comment.

Bo is serving a life sentence for bribery, embezzlement and abuse of power. He says that someday he will be vindicated.

Gu was sentenced to death for murdering Heywood. In December 2015, Chinese authorities reduced her punishment to life in prison.

The court judgment against Bo ordered the villa be confiscated by the Chinese government. Chinese state media reported in 2014 that it was up for sale.

Suggested price: $8.5 million.