Michael Jordan, Sandra Bullock and Paris Hilton holiday there. Justin Timberlake and Janet Jackson wrote lyrics about it.

But, last week, the Caribbean island of Anguilla drew attention for other reasons.

The paradisiacal tax haven slipped further down a key global transparency index, according to a new report by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Anguilla is now considered “non-compliant” with standards on how countries share information about people and companies suspected of avoiding taxes or committing financial crime, according to the OECD’s Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes report. The territory had previously been ranked as “partially-compliant” in 2014.

The island partially blamed its slide on the fallout from the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists’ 2016 Panama Papers investigation. Malta, another tax haven, also regressed, according to the Paris-based organization.

Anguilla, a flat coral island that is one of the United Kingdom’s Overseas Territories, received 53 requests from other countries seeking information about Anguillian companies between 2015 and 2017. It responded with details in only nine cases, according to the OECD. This, combined with concerns about Anguilla’s ambiguous laws and poor record-keeping, saw the territory rated as either partially-compliant or non-compliant for four out of 10 tax transparency measures, the OECD wrote.

“It is not clear whether reliable accounting records are actually maintained and there is no measure to incite entities to do so,” the OECD found. The economic body said it was also “not clear” whether firms that help create and manage Anguilla offshore companies are legally required to know the owners of those entities.

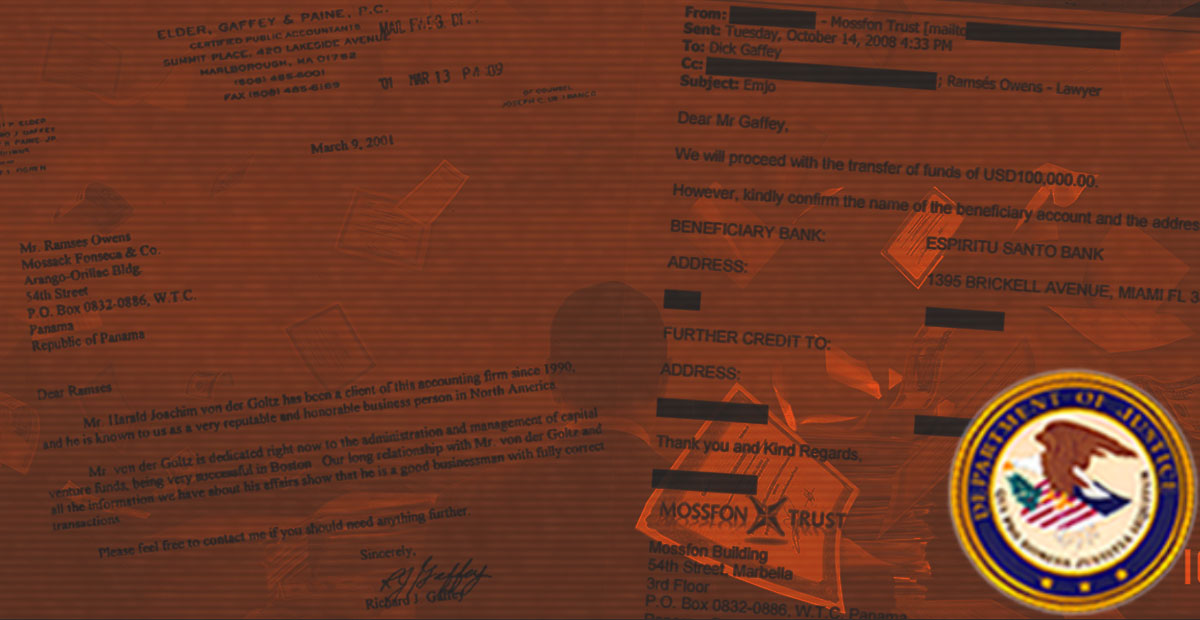

Anguilla blamed the “poor governance structure” of Mossack Fonseca, the international law firm whose leaked files formed the basis of the Panama Papers investigation, for its inability to answer other countries’ requests for basic corporate information.

When Mossack Fonseca collapsed in the wake of the Panama Papers scandal, its Anguilla office closed and records disappeared. “The disorderly winding down of this Panamanian Service Provider hampered access to information in relation to such companies and reflected negatively in Anguilla’s overall ability to exchange information,” the OECD report said. Of the requests made to Anguilla during the period of the OECD’s review, 90% were about companies created by Mossack Fonseca.

“Out of all the territories, Anguilla struggles the most in some ways,” said Peter Clegg, a Caribbean politics expert at the University of the West of England Bristol, noting that it is poorer than better-known neighbors like the British Virgin Islands and the Cayman Islands. “Anguilla has been one of those semi-forgotten territories,” Clegg said, “not large enough to be comfortably self-sufficient but not in crisis enough to gain U.K. financial support.”

Carlyle K. Rogers, an Anguillian barrister and offshore service provider, defended the island and said that the country has limited resources to meet the OECD’s demands. “The OECD continues its anti-free market and imperialistic crusade against Anguilla,” Rogers told ICIJ. “The OECD will have no credibility on these matters until the same standards are applied to its own member states including the U.S., with specific reference to the states of Delaware and Nevada.”

The U.S. was named as the world’s second-most secretive jurisdiction behind the Cayman Islands, according to the Tax Justice Network’s 2020 Financial Secrecy Index.

Home to more than 17,000 people, Anguilla’s financial services sector has a well-documented history of attracting customers whose interest in the island is unusual or downright criminal. The European Union, as well as France and the Netherlands, have blacklisted Anguilla for its lack of transparency.

The Panama Papers investigation, for example, revealed that an alleged Slovenian drug dealer opened a company in Anguilla. Requests sent to Mossack Fonseca by Anguilla’s financial investigations agency also show that the island suspected that Anguillian companies were misused by fraudsters.

Documents from ICIJ’s 2017 Paradise Papers investigation show that a Fort Lauderdale startup financier set up an Anguillian company to help avoid creditors, according to an email by the businessman’s Morgan Stanley banker.

Documents from the Panama Papers investigation reveal Anguilla enthusiastically courted Mossack Fonseca when the offshore law firm expressed an interest in working on the island.

Ramon Fonseca, one of the company’s founders, visited Anguilla in 2005, according to emails. He stayed at a beachfront resort, according to travel bookings.

“We are relatively informal in Anguilla and meetings can be arranged at short notice,” John Lawrence, then head of Anguilla’s financial services commission, told Mossack Fonseca.

The law firm negotiated special rates to entice the rich and powerful to buy companies on the island, according to discussions with officials. Under an agreement with the Anguillian government, Mossack Fonseca promised to try to create at least 1,000 Anguilla companies each year.

The law firm emphasized secrecy, telling Anguillian officials that 90% of its clients “prefer bearer shares since they have limitation to provide us information on the beneficial owner.” Bearer shares, once popular with criminals and which featured in the Netflix movie The Laundromat, allow shareholders extra anonymity because they do not record names on the paperwork. Anguilla banned them in 2018.

Mossack Fonseca advertised Anguilla to clients as offering a “cheaper alternative” to the British Virgin Islands, according to emails. The law firm opened on the island in 2007. By 2016, the island had become one of Mossack Fonseca’s top four jurisdictions for incorporations.

Traces of Mossack Fonseca’s Anguilla operation are now hard to find. The company’s first representative on the island, former police cadet Sherma Baptiste Harrigan, now lives in St. Louis, Missouri, according to public records.

A freelance investigative reporter visited the tidily-trimmed street this week. The apartment’s owner, like many owners of Anguillan companies once sold by Mossack Fonseca, could not be found.

Emily Wolf, a freelance investigative reporter, contributed to this story.