The Panama Papers investigation deposed heads of governments and resulted in the recovery of hundreds of millions of dollars.

But it also changed the the worldwide understanding of a cleverly contrived and continuously evolving system that swells and protects the riches of the wealthy and powerful.

The journalists who worked on the Panama Papers look back on the project through different lenses, but taken together, they reflect a world in flux.

Sol Lauría, an Argentinian journalist who has worked in Panama since 2013, witnessed the Panama Papers up close like few others.

Lauría said that one of her strongest memories during the months before publication is “seeing the evidence -such as documents, emails or messages with [offshore lawyer Ramon] Fonseca’s own handwriting- of information that we already knew but had never been able to prove due to the lack of access to the information in offshore jurisdictions.”

In 2017, Lauría nabbed a rare three-hour interview with Mossack Fonseca co-founder, Fonseca, in his apartment in Panama City.

“Ask what you want,” Fonseca said to Lauría, who has written a profile on the offshore lawyer for an upcoming book.

Fonseca, writes Lauría, “is a man of medium and resounding stature who lost several pounds after the Panama Papers. He exercises with a personal trainer every day after a routine that he clings to as his only defense: from an early hour he checks to see if he has been sued in some corner of the world, then reads and later tries to write.”

On the couch in a small, dark room, Fonseca told Lauría that there was a lot of sensationalism in the Panama Papers.

“You do not regret anything?” Lauría asked.

“No,” Fonseca replied. “We take risks, of course, because everything in life is risk. But we did nothing illegal.”

Lauría wrote that Fonseca’s “verbiage at times is dark, at times graceful or melancholy. When he speaks of Panama Papers, he is always unrepentant, as if seeking to shield himself with repetition.”

“I consider myself a balanced man,” Fonseca replied. “I hardly regret it. I know that I am not perfect, but I do not have an enormous ego.”

“Do you not find anything questionable, however lawful?” Lauría asked again

“But everyone does it! Everyone uses the system!” Fonseca told Lauría. “The world’s savior does not understand that the capitalist world is managed by corporations. The world does not subsist with the state bureaucracy. And we can’t stop encouraging those who want to create wealth, create business, create ideas. Please…”

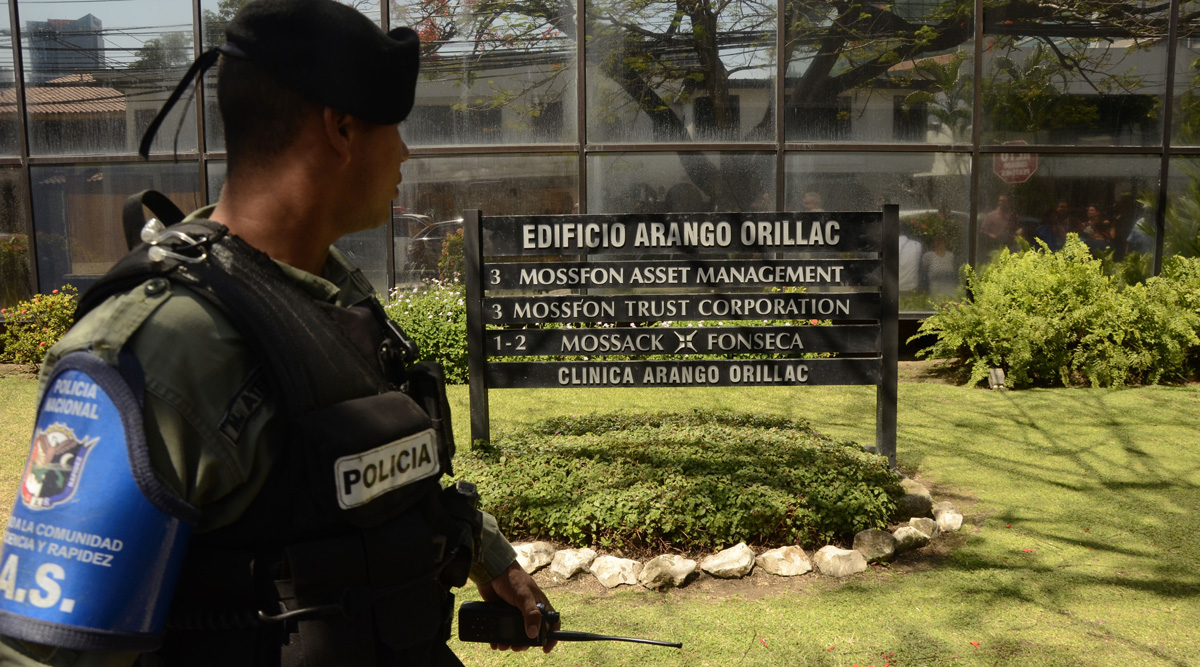

Despite Fonseca’s protestations and after some pushback from the Government of Panama that initially claimed it, too, had done little wrong, Lauría sees some changes.

Panamanian authorities sanctioned delinquent offshore companies with financial penalties and closed down more than 275,000 offshore companies. New rules, long-resisted, require Panama to collect and swap certain financial information with other governments.

“We will see how it is implemented,” Lauría said.

While Panama looked to update its laws, in other nations it was the lawmakers themselves facing public scrutiny over their finances.

After 15 months of protests, lawsuits, and vitriolic online debates across Pakistan, prime minister Nawaz Sharif stepped down from power in July 2017.

Sharif was the second prime minister to lose office because of the Panama Papers, following the more rapid departure of Iceland’s leader, Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson.

Umar Cheema, an investigative journalist with The News in Pakistan, led reporting on the offshore holdings of Sharif’s family members.

Cheema said that the Panama Papers was “a tour through the underworld of the rich” that has left a permanent mark on him.

“They enjoy all the privileges, milk all the benefits and rig the policies,” Cheema said. “Nevertheless, they park wealth abroad.”

Bastian Obermayer is the German journalist who received the first message from John Doe, the anonymous whistleblower who provided Süddeutsche Zeitung with the data for the Panama Papers.

Obermayer and his colleague, Frederik Obermaier, chose to share the 11.4 million documents with the International Consortium of Journalists (ICIJ) on the understanding ICIJ would assemble a coalition of reporters around the world.

Asked about what the biggest change is since the project, Obermayer points to two things.

“Although there’s even a new anti-offshore law in Germany that’s called the “Panama Plan,” Obermayer said, “I think the biggest change is that people are aware now of the menace that the anonymous offshore world poses.”

“The biggest change is the one in the heads.”