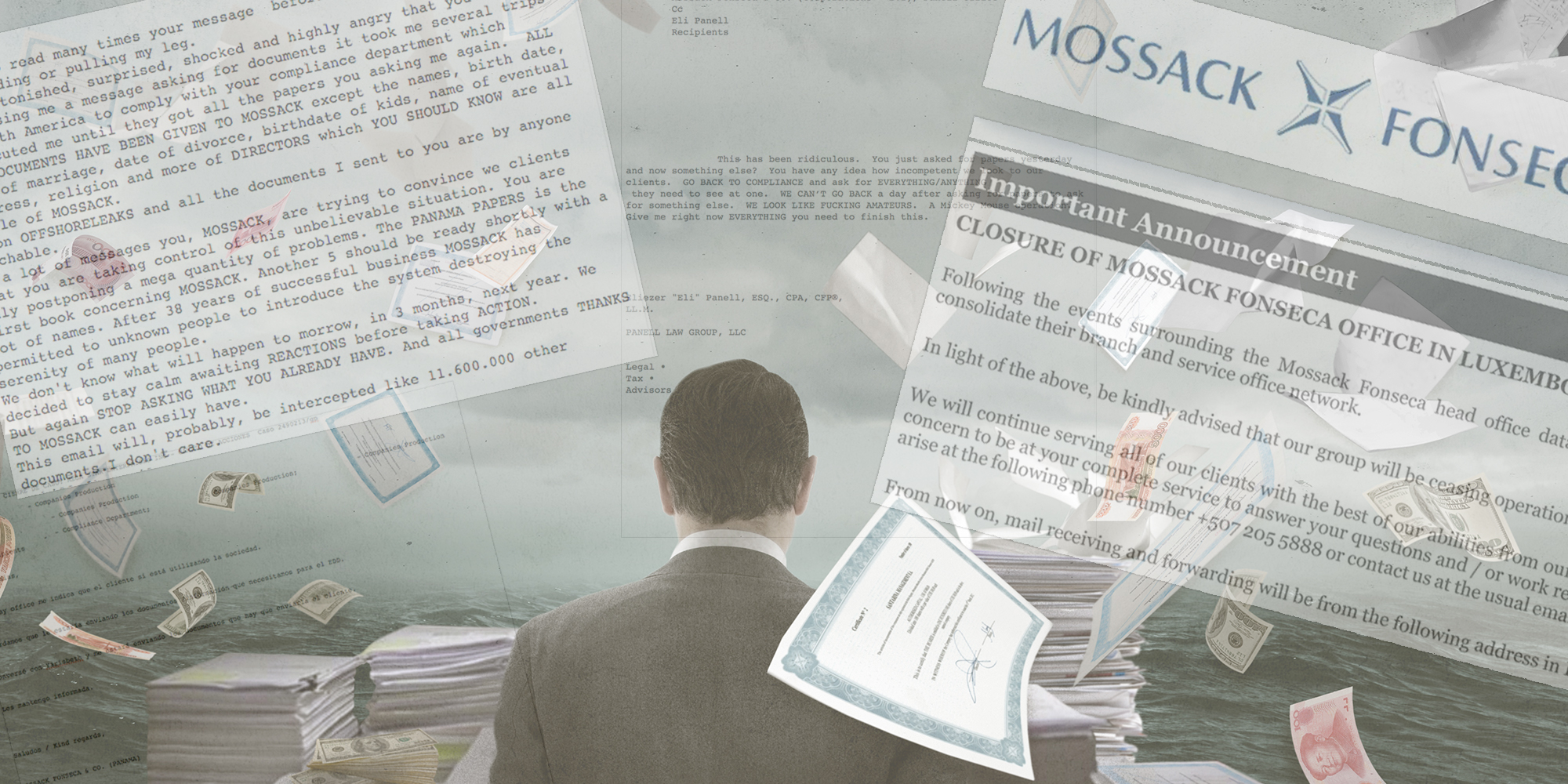

A fresh leak of 1.2 million documents from the law firm at the center of the Panama Papers has unveiled secrets about how some of the world’s richest, powerful and most famous people made — and concealed — their money.

In some cases, the new passports, bank statements, emails and other documents upend previous defenses and explanations by politicians and superstars when confronted with the Panama Papers findings.

Here are a few of the latest stories from the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists’ global media partners:

Frozen bank accounts in Ecuador

ICIJ’s partner El Universo reported that Switzerland’s federal prosecutor had frozen accounts belonging to the former manager of Petroecuador as part of a bribery investigation into a dozen companies created by the Panama law firm Mossack Fonseca.

According to documents from the latest Panama Papers leak, Swiss bank SYZ notified Mossack Fonseca in September 2016 that the prosecutor had ordered a freeze on assets held by the state oil company’s former manager, Alex Bravo Panchano, or his company Johanna Investment Corp.

The action came months after the initial publication of ICIJ’s Panama Papers investigation. As part of that investigation, El Universo had reported that four offshore companies in Panama were tied to the former Petroecuador manager.

One of them Girbra, S.A., had signed an agreement with a Petroecuador contractor.

Laying out the grounds for his investigation, Swiss prosecutor Frederic Schaller said that Bravo is suspected of providing at least $35 million in benefits to his associates in the process of awarding of 142 Petroecuador contracts, according to El Universo.

Russian passports in Ukraine

The new Panama Papers documents contain a headache for the mayor of major Ukrainian port town Odessa.

Mayor Gennadiy Trukhanov denied reports when the Panama Papers investigation first broke in April 2016 that he held a Russian passport.

Holding second citizenship is illegal in Ukraine, and connections to Russia are particularly fraught following years of Russian interference, reported ICIJ partner OCCRP.

Trukhanov was connected to offshore companies used in the construction business, according to the original Panama Papers reporting. In those files, Trukhanov was listed as having a residential address in northeastern Russia, raising suspicions of a Russian connection.

Trukhanov denied Russian citizenship. Ukrainian and Russian officials leaped to the mayor’s defense.

The new files show the opposite: a Russian passport bearing Trukhanov’s name and personal information.

Trukhanov, who is also under investigation in Ukraine for embezzling state funds during the purchase of a factory, did not respond to OCCRP’s request for comment.

Peru’s offshore arms dealer

In Peru, Convoca made a startling discovery with the newly-leaked documents: although Mossack Fonseca had set up offshore company GSS Group Ltd in 1993, the law firm only learned in September 2016 that the company’s owner is fugitive arms dealer Moshe Rothschild.

The company was used for dredging and other maritime activities, according to the Panama Papers.

In the 1990s, Rothschild allegedly tried to bribe Peruvian officials to buy used Soviet fighter planes. Peru has indicted the former Israeli air force pilot on five corruption charges, according to Convoca. Rothschild has eluded Peru’s legal requests to return to Peru to face corruption, bribery and other charges.

Feuding signatures in Slovenia

The new Panama Papers documents reveal that a senior representative of a Chinese pharmaceutical company Menovo may have misused the passport of a European medicines inspector to set up offshore companies in the inspector’s name, according to news organization Oštro.

The Slovenian inspector of a government agency who inspected a factory for the major European medicines producer Krka denied wrongdoing in 2016. He filed a criminal complaint for identity theft and was dismissed by his employer.

The passport copy used to set up the offshore companies seems to bear a different signature from the inspector’s real passport, reported Oštro. Mossack Fonseca employees performed an internal check and confirmed the irregularity after receiving questions from Slovenian reporters in 2016.

“Signatures…are NOT the same,” confirmed a Mossack Fonseca employee in March 2016 after receiving questions from journalists.

A Chinese intermediary who is the chairman of the Chinese pharmaceutical company that supplies Krka, shared with Mossack Fonseca the disputed passport copy used to open offshore companies, Oštro said. The company and its executive denied wrongdoing and blamed Mossack Fonseca for “poor management.” The Chinese factory produces materials used in Krka’s medical products sold in the European Union.

Yemen’s ‘Sugar King’

The new Panama Papers documents reveal further details about how one of Yemen’s top corporate titans may have skirted international sanctions by paying rebels through shell companies.

Shaher Abdulhaq, known as Yemen’s Sugar King for his dominance of the country’s soft drink market, has also accumulated power in Yemen’s cell phone market.

Abdulhaq’s company Spacetel Yemen merged with cell phone giant MTN in 2006. He did this through a web of offshore companies that concealed his ownership, according to the Panama Papers documents.

The new Panama Papers files reveal in more detail than ever the shareholders and owners of MTN Yemen, including Abdulhaq and close associates.

During Yemen’s lengthy conflict, MTN Yemen has sent regular text messages to millions of subscribers with invitations to contribute to the rebel “war effort” with 47 cent donations, according to ICIJ media partner Arab Reporters of Investigative Journalism (ARIJ). Last year, a United Nations expert panel warned of the rebels’ exploitation of mobile phone technology in general to raise money to avoid international sanctions.

Through offshore companies, ARIJ wrote, Abdulhaq “contributed to breaking the UN Resolutions…. by transferring funds to individuals and entities carrying out actions that threaten peace, security and stability in Yemen.”

Abdulhaq and MTN Yemen did not respond to ARIJ’s requests for comment.

Paraguay’s honorary consul

ICIJ media partner in Paraguay, ABC Color, revealed that the South American nation’s honorary consul to Monaco was — without the knowledge of officials who approved his quasi-diplomatic position — an Italian convicted felon.

Carlo Sama, a former executive of Italy’s second biggest company Ferruzzi, who now lives in Monaco, was convicted in 1995 of involvement in a scheme that funnelled almost $100 million dollars to Italian politicians as part of a “super bribe,” according to media reports.

Following publication of ABC Color’s investigation, Paraguay’s foreign affairs ministry announced an investigation into Sama’s position.

ABC Color also revealed that an Italian-born leather import-exporter who now lives in Paraguay, Donato Verlato, had previously evaded up to one million euros in tax on leather shipped from Latin America to Italy. The law firm Mossack Fonseca appeared not to know the customer’s background before the Panama Papers’ revelations.

“The tanner entrepreneur managed not to pay a single euro thanks to a careful and well-assembled scheme of false invoices,” ABC Color wrote.

Before Verlato’s arrest in May 2011, ABC Color reported, he had set up a shell company in the British Virgin Islands.