WHISTLEBLOWERS

Plaintiff seeks to anonymously sue Germany for alleged breach of contract to share revenue raised due to Panama Papers’ tax fraud investigations

Unorthodox case prompts whistleblower advocate to question if Germany is running an ad hoc rewards program for whistleblowers that lacks formal protections.

A person claiming to be the whistleblower behind the Panama Papers is attempting to sue the German government and federal criminal police anonymously in a complex legal and financial dispute over an alleged deal to purchase the leaked dataset, according to a recent lawsuit filed in the United States.

On July 3, the Washington D.C. judge in the case, Chief Judge James Boasberg, ruled that the plaintiff could proceed with it using a pseudonym publicly — but would have to reveal their identity to the court.

The anonymous plaintiff argues that they should not have to provide the court with identifying information, as it would put their life in danger.

The plaintiff has accused German authorities of reneging on an alleged agreement to pay the source 10% of revenue over a 50 million euro threshold recouped from investigations into tax fraud and other financial offenses based on the trove of files, which Germany purchased in 2017, and is seeking more than $14 million in compensation.

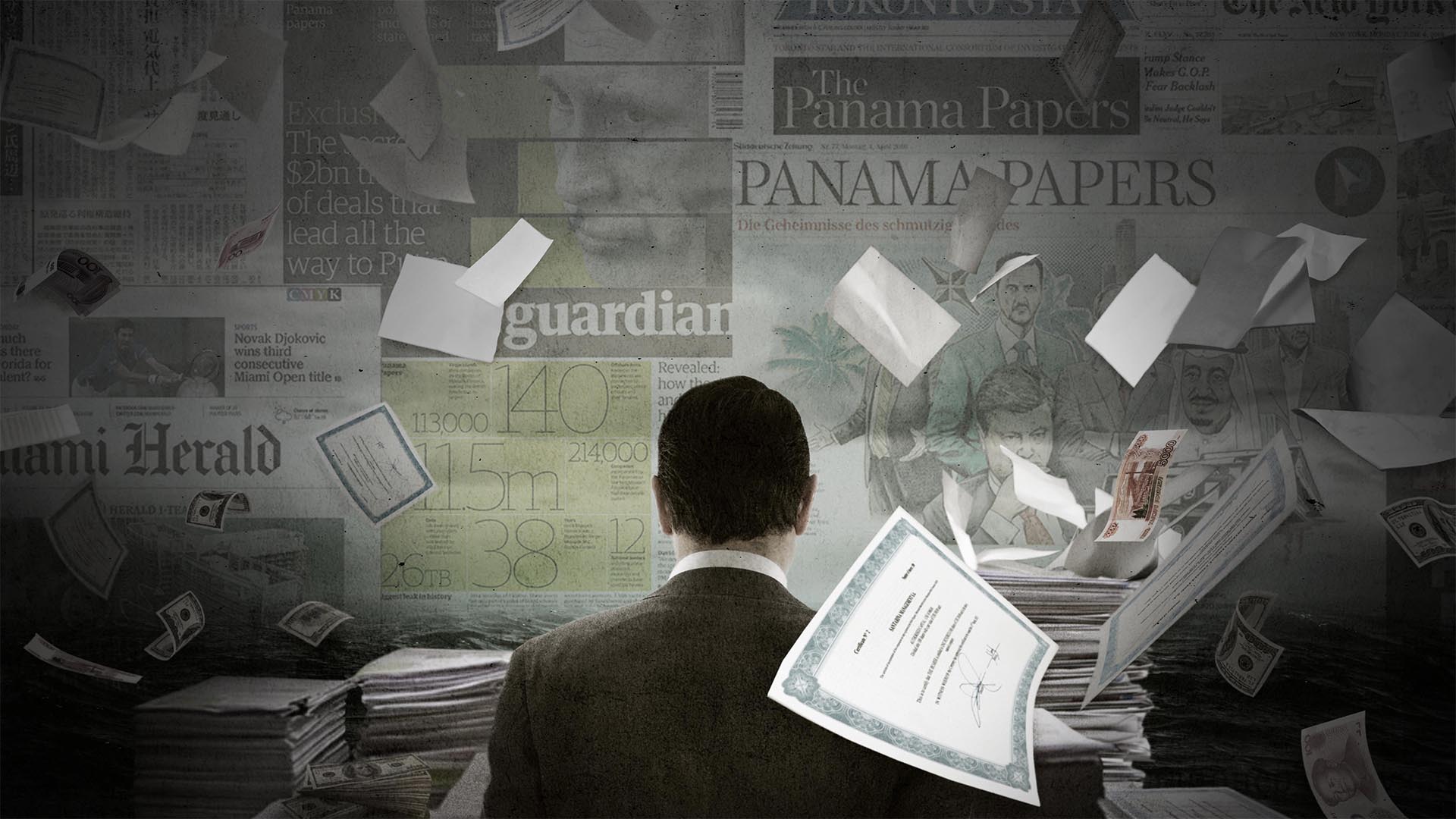

In early 2015, the 11.5 million documents that later became known globally as the Panama Papers were leaked to the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung, which shared them with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. ICIJ brought together a team of hundreds of investigative reporters from around the world, and their stories — published in Süddeutsche Zeitung and more than 100 media outlets — exposed the secret offshore holdings of world leaders, celebrities, criminals and more.

ICIJ is not commenting on its sources and never pays for information.

Known only as “John Doe,” the whistleblower behind the huge leak has always insisted on maintaining his anonymity, saying it is essential to ensure his survival.

After the 2016 Panama Papers’ investigation exposed financial corruption and crimes by some of the world’s most powerful people, he issued an 1800-word manifesto explaining his thinking entitled “The Revolution Will Be Digitized.”

Coincidentally, “John Doe” is a fictitious name typically used for anonymous male litigants in U.S. courts, and it is being used for the plaintiff in this case — but the court stated that the pseudonym did not suggest anything about the person’s sex.

In rare public statements several years apart, the Panama Papers whistleblower has said that he has feared for his life and for his family’s safety, and that all whistleblowers deserve greater protection.

The unknown court claimant is representing themself in the action first lodged in June in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia.

German authorities declined to comment.

The court filings allege previously unreported information about the whistleblower’s thorny negotiations with Berlin for compensation and protection in the aftermath of the massive leak.

In a written response to questions sent to an email address listed as part of the legal filings, the anonymous plaintiff told ICIJ that their lawsuit “should be a clear sign to the European Union that EU-wide whistleblowers protections are necessary.”

The person wrote that they had filed a motion to appeal the ruling that they must identify themself to the court.

Their emailed response further warned of the global repercussions of failing to take issues regarding the protection of whistleblowers seriously, stating: “[W]hile Germany played games Putin invaded Ukraine.”

In their comments to ICIJ, the plaintiff cited the IRS whistleblower program, which includes provisions to pay sources for sharing information, as a potential model for the European Union. Jennifer Gibson, the legal director of The Signals Network, an international whistleblower support organization, said that if the complaint is accurate, the German government is running an ad hoc system to pay whistleblowers that lacks the formal protections of the U.S. system. As a result, she said, it “leaves whistleblowers unprotected, at risk and with no safe options when things go wrong or disputes arise.”

“Germany should decide — does it want to run a whistleblower reward program or not?” she said. “If it does, then it should set up a transparent, formalized system that protects whistleblowers and prevents the type of backroom deals that allegedly occurred in this case.”

Germany should decide — does it want to run a whistleblower reward program or not?

— Jennifer Gibson, the legal director of international whistleblower support organization The Signals Network

The complaint outlines a perceived “serious threat posed to [the] Plaintiff’s life by numerous powerful and corrupt businessmen and politicians” who were exposed by the Panama Papers revelations, and states that the whistleblower recognized they would need money to protect themselves after the investigation’s release.

The plaintiff states in the complaint that a “market exists for leaked tax data” and the German government had “paid in the past for data similar to the Panama Papers.” In early 2015, German authorities used evidence from an earlier Mossack Fonseca dataset it had purchased to launch a raid on a bank — data that ICIJ and Süddeutsche Zeitung also already obtained at that time.

According to the court filing, in late 2016 and early 2017, the plaintiff began a months-long negotiation to sell the papers to Germany’s federal criminal police, known as the BKA, which sought to use the leak to uncover financial crimes and collect tax revenues.

The complaint says the plaintiff, a U.S. citizen, accelerated the negotiations after the 2017 inauguration of Donald Trump, whose business interests came up several times in the Panama Papers. According to the court filing, the plaintiff says they traveled to Germany in February 2017 to continue negotiations with the BKA, which they accused of dragging out the talks, endangering the whistleblower’s safety, and eventually forcing them to pay rent at their German safe house.

On June 23, 2017, however, the BKA and the whistleblower allegedly struck an agreement. The plaintiff included a document in their court filing written on BKA letterhead signed by “Vice President Henzler,” which the complaint says refers to BKA Vice President Peter Henzler, that lays out the alleged deal: The whistleblower would receive an initial payment of 5 million euros (about $5.6 million at the time), and 10% of any funds the German government collected as a result of the Panama Papers above 50 million euros.

The BKA confirmed in a July 2017 press release that it was in possession of the Panama Papers, and anonymous German government sources said Berlin paid 5 million euros for them. A BKA spokesperson declined to comment to ICIJ about the lawsuit or how the papers were obtained.

The complaint alleges the source received the initial “post-tax” payment of 5 million euros, but that BKA officers told them the funds recovered were far below the 50 million euro threshold that would entitle them to further payments. On April 9, 2021, BKA officers allegedly told the whistleblower that 13.5 million euros ($16 million at the time) had been recovered as a result of the Panama Papers. That same month, ICIJ reported that Germany recovered $195.7 million as a result of the leak.

The plaintiff wants the U.S. court to order the German government to pay them at least $14.5 million.

The complaint says that neither ICIJ nor its partners paid for the Panama Papers, which were provided “to expose a wide variety of crimes.”

In addition to the struggle to maintain their anonymity, the plaintiff must also convince the court that it has jurisdiction over their case — challenges likely made more complex by the fact that they do not have legal representation. The complaint argues that the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act (FSIA), a law that establishes criteria for when foreign states can be prosecuted, gives the court jurisdiction; the plaintiff told ICIJ that “there is no question” the FSIA applies.

Scott R. Anderson, an expert in national security law and a fellow at the Brookings Institution, told ICIJ the matter was complicated. “The plaintiff may well have a plausible case … [but] it faces some serious and complex jurisdictional hurdles,” he said.

The best way for the plaintiff to win this argument and secure his anonymity, Anderson said, was to hire a lawyer to represent them. “At best, these are close and contested legal issues that don’t have clear answers.”