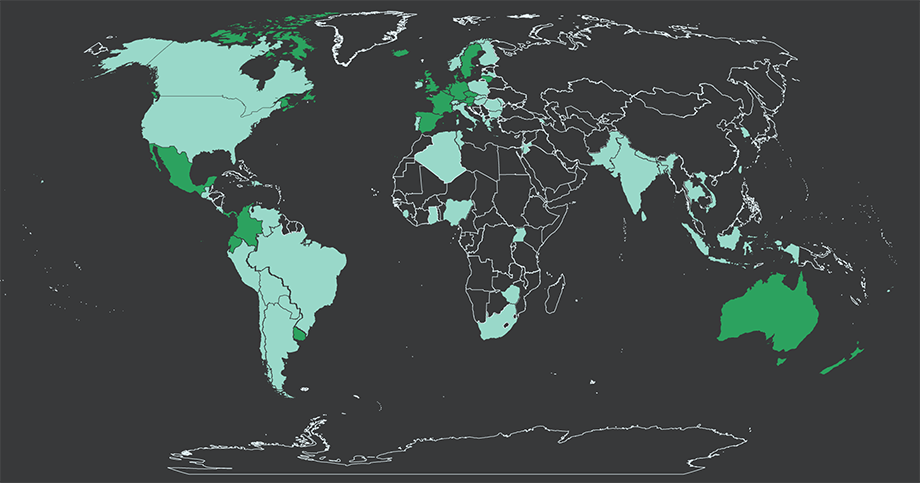

There is an immediate increase in offshore incorporations when governments get serious about tackling organized crime, according to a report based on data from the Panama Papers.

The study by researchers from Monash Business School and the University of Adelaide, Australia, and the University of St Gallen, Switzerland, found that offshore incorporations increased in well-governed countries immediately after media reports of asset confiscations and expropriations.

“In countries with strong rule of law and well-developed institutions, state confiscations and expropriations are key to deterring and prosecuting crime,” according to one of the study’s authors, an associate economics professor at Monash University, Paul Raschky.

“One can imagine criminal figures or organizations moving assets out of the country to escape precisely this risk.”

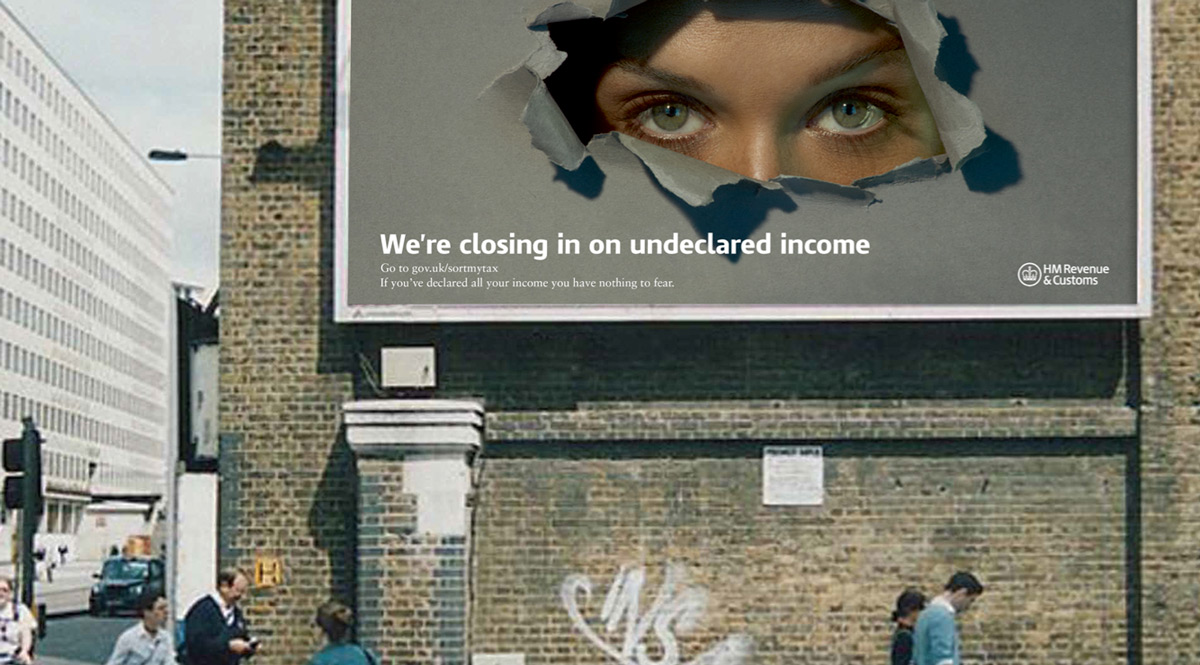

Aside from dodging tax, governments must recognize the “little-discussed fear” of losing illegal assets when governments clamp down on criminality.

“Policymakers must not overlook offshoring as a means to hide assets from honest governments that are ramping up their law enforcement efforts,” Raschky said.

Apologists for tax havens have long argued that they offer necessary protection to individuals or organizations whose legitimate assets may be subject to seizure by tyrannical regimes.

Although the study found no evidence to support this assertion, Raschky said it could not be ruled out. However, the research did find an explicit, direct correlation between fear of expropriation and an immediate rise in offshore incorporations in wealthy countries with strong governance.

“The effect is driven by countries with non-corrupt and effective governments, which supports the notion that offshore entities are incorporated when reasonably well-intended and well-functioning governments become more serious about fighting organized crime by confiscating proceeds of crime,” the report states.

The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists together with the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung and more than 100 other media partners, spent more than a year sifting through 11.5 million leaked Panama Papers files to expose offshore holdings.

The files, which were leaked to Süddeutsche Zeitung, came from a little-known but powerful law firm based in Panama, Mossack Fonseca, that had branches in Hong Kong, Miami, Zurich and more than 35 other places around the globe.

On the third anniversary of the publication of the Panama Papers in April, ICIJ reported that governments around the world had recovered a total of $1.2 billion in fines and back taxes resulting from the exposure of the offshore finance industry.