Investigators from the U.S. attorney’s office met with officials of the Metropolitan Museum of Art earlier this month to discuss whether relics in the famed museum’s collection had been stolen from ancient sites in Cambodia.

Museum officials said that “new information” about some pieces in their collection spurred them to reach out to officials in the Southern District of New York. They declined to describe what facts precipitated the meeting, which occurred about two weeks ago.

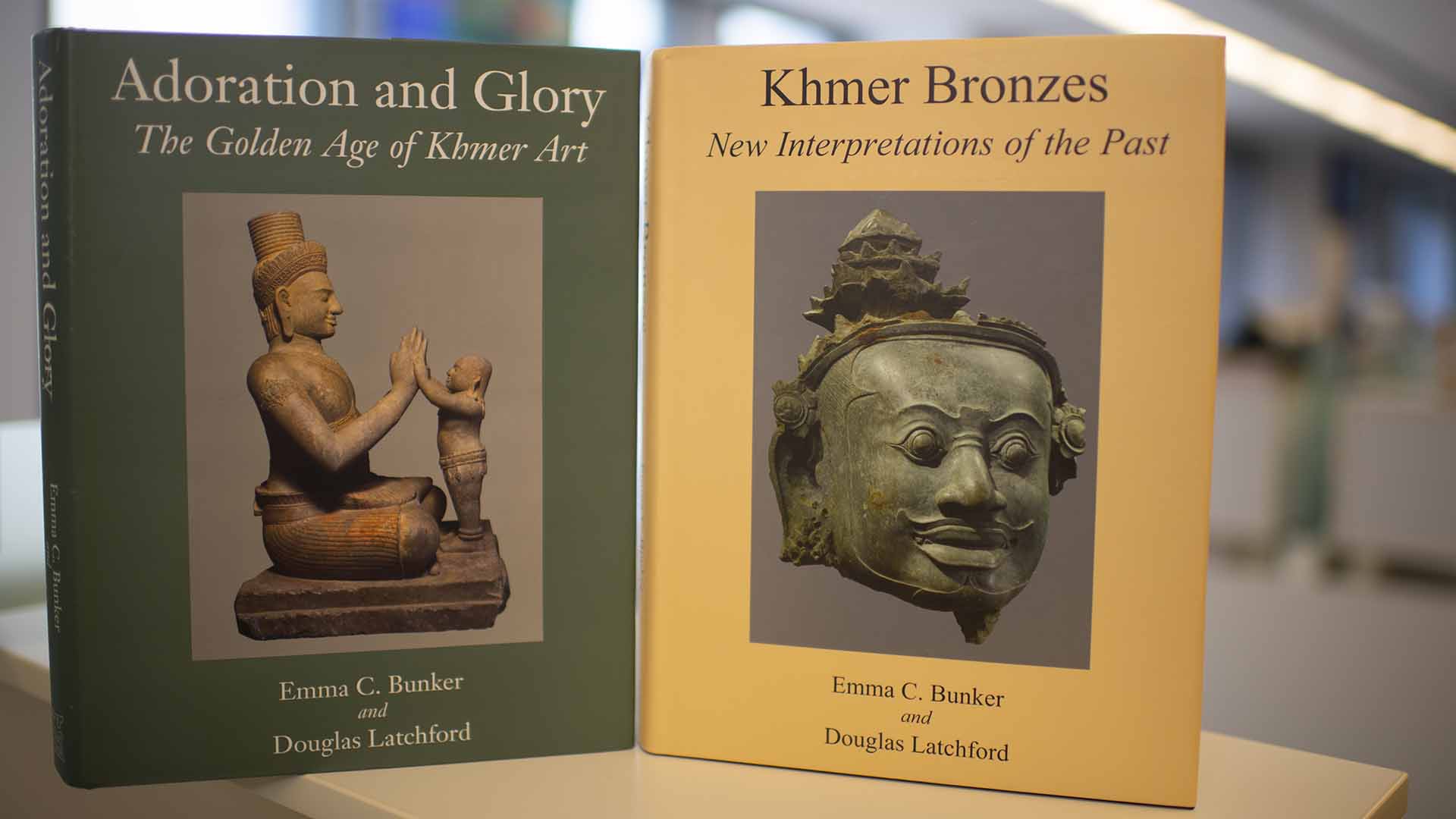

The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and the Washington Post reported three weeks ago that the Met holds 12 pieces once owned or brokered by Douglas Latchford, a man prosecutors said was involved in decades of trafficking in looted artifacts. Another seven pieces at the Met came to the museum through his associates.

The reporting revealed that Latchford had created two offshore trusts that held relics. Those trusts were exposed in the Pandora Papers, a trove of more than 11.9 million financial records obtained by ICIJ and shared with news organizations around the world.

In total, according to the investigation, 10 museums around the world were holding at least 43 relics that had passed through the hands of Latchford or those of his associates.

The Met’s move to meet with investigators comes as the Denver Art Museum is preparing to return four pieces to Cambodia that also had been cited in the Pandora Papers.

“Recently, in light of new information on some pieces in our collection, we reached out to the US Attorney’s office – to volunteer that we are happy to cooperate with any inquiry,” the Met said in a statement Sunday. “The Met also has a long and well documented history of responding to claims regarding works of art, restituting objects where appropriate, being transparent about the provenance of works in the collection, and supporting further research and scholarship by sharing all known ownership history.”

Bradley Gordon, an attorney representing the Cambodian government, said that the Met has not contacted government officials there regarding the pieces.

“The amazing thing is that these museums say they’re researching [the relics’ origins] but they have not contacted us,” Gordon said. “How can they say they’re researching when they aren’t calling the country of origin?”

The Met reached out to U.S. authorities after ICIJ and The Post sent the museum detailed questions about pieces linked to Latchford, Gordon said.

Officials with the U.S. attorney’s office in the Southern District of New York declined to comment Monday.

Cambodian investigators have been researching pieces they believe were looted during decades of war and tumult in the country beginning in the 1970s, when thieves ravaged the treasures of the ancient Khmer Empire. Today, scholars say, many valuable pieces sit in prestigious private collections and museums around the world.

Phoeurng Sackona, Cambodia’s Minister of Culture and Fine Arts, said she was surprised to learn that the Metropolitan Museum of Art had acquired so many Khmer relics during periods of war and tumult in Cambodia. “The Cambodian government never gave permission for our national treasures to be trafficked to the United States,” she said.

“Today, we wish for the Metropolitan Museum to act as a moral and just leader in the global museum community and to return our precious looted antiquities to our people.”

In 2013, the Met returned two pieces to Cambodia, and the museum says that it has conducted research to determine whether other pieces in its collection have been acquired legally.

But critics say the Met, like other museums, has been reluctant to investigate Cambodian pieces that likely have been looted.

Tess Davis, the executive director of the Antiquities Coalition, an organization that campaigns against the trafficking of cultural artifacts, criticized the museum for not responding more thoroughly after a Latchford associate was indicted in 2016 and Latchford himself was indicted three years later.

“The Met owed it to Cambodia — and itself — to do a full and public accounting of its Khmer collection then. That didn’t happen,” Davis said. ”There has still been no full and public accounting from the Met. It’s never too late to do the right thing, but what is the Met waiting for at this point?”

The Met collection, for example, has a sandstone statue of a figure called a Harihara.

The information published by the museum says the piece came from southern Cambodia and describes its style as “pre-Angkor period.” A very similar piece is described in the Latchford indictment — same religious figure, same dealer, same period, same location.

According to the indictment, Latchford had consigned the Harihara to a dealer who helped him sell looted art in 1974. The museum bought its Harihara from the same dealer three years later.

In a written statement last month, a spokeswoman for the Met said it was “unknown” whether the Harihara in its collection is the same as the Harihara that prosecutors say was looted. Latchford died before trial.

In recent years, the Cambodians have assembled a team of archaeologists and art experts in an effort to recover their looted national heritage. One of the people who has been critical to repatriation efforts is a former looter from Latchford’s network known as the “Lion,” who has been helping archaeologists excavate temples from which he had stolen relics, in order to recover fragments that might help ensure their return.

The group has begun to compile a list of treasures that the team believes were looted. According to the records, there are 45 relics in the Met’s collection that are highly significant culturally, and which the team members believe were looted. The “Lion” said that he recognized 33 of the relics as pieces he had stolen himself, and another 11 that he or others in his network had stolen versions of, according to Cambodian officials.

Gordon, the lawyer representing the Cambodians, said that his team recently sent the list of 45 relics to the U.S. attorney’s office. The Cambodian government wants all of the objects returned.