The head of the United States’ financial crime fighting unit says his agency is coming up short in the battle against dirty money due to a lack of resources.

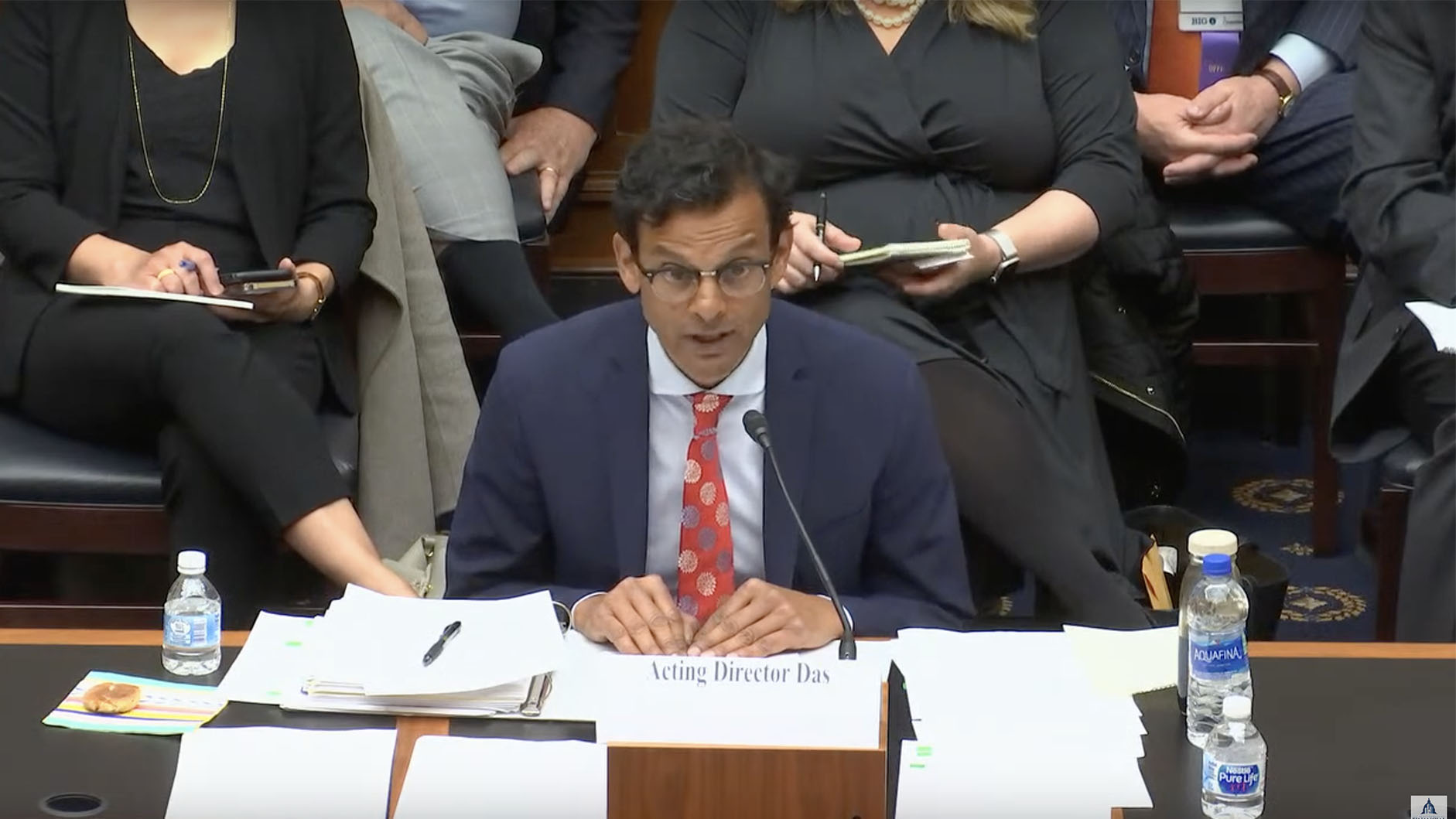

The Financial Crimes Enforcement Network’s acting director Himamauli Das told a congressional committee that his small team is “incredibly talented,” but “outmatched” in policing cryptocurrency exchanges and behind on creating a beneficial ownership database.

“As you are aware, we are missing deadlines,” Das told members of the U.S. House Committee on Financial Services on Thursday. “To be blunt, we will likely continue to do so because our budget situation has required us to make significant trade-offs among competing priorities.”

A key priority for the agency is creating the ownership database, or registry, mandated by the Corporate Transparency Act, which was enacted over a year ago. Under the law, millions of companies incorporated in the U.S. must report, for the first time, the names of their true owners to the federal government. Law enforcement officials and compliance officers at banks and other financial institutions would have access to the database, allowing them to more easily pursue investigations or shut off accounts with links to criminal actors.

After providing the Treasury office tens of millions of dollars less than it had asked for, Congress has left the agency scrambling to implement key pieces of the landmark anti-money laundering law, Das said at the hearing.

As the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists has reported across multiple investigations, anonymous companies are a major vulnerability in the global fight against tax avoidance and money laundering. Drug cartels, oligarchs, despots and the global elite use them to conceal fortunes from tax authorities and law enforcement.

The United States plays a big role. Delaware, Wyoming and Nevada are among the world’s top locations to set up anonymous companies.

The Corporate Transparency Act was attached to a massive national defense funding bill that Congress passed in late 2020 with a veto-override. The law, supported by both the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and left-leaning Public Citizen — an unusual Washington alliance — was the result of years of negotiations.

The FinCEN Files, a global investigation on dirty money flows led by ICIJ and BuzzFeed News, was credited with helping to get the legislation over the finish line in 2020.

Establishing a registry of company owners was a key reform that experts said was needed in response to ICIJ investigations. The issue has increased in relevance after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February and a flurry of new sanctions of Russian oligarchs and companies. Several weeks ago the U.S. government announced a program to identify and freeze oligarch assets, which are often hidden under layers of shell companies, including in the U.S.

Yet a new era of corporate transparency can only come into effect when FinCEN finishes drafting the exact rules that will govern the company ownership data collection and distribution under the new law.

Notably, Das declined to commit to a specific timeline for launching the all-important company ownership program when lawmakers asked if it will be completed by the end of this year. “I do not have a timeline for the establishment of the database,” Das said. “We’re working incredibly hard given the resource constraints we have.”

Anti-money laundering experts have argued that the Treasury agency is underfunded and overstretched in its role as the world’s leading dirty money watchdog, even with funding boosts sought by the Biden administration. FinCEN is staffed with roughly 300 employees including data analysts, investigators, enforcement offices and policy wonks.

At the hearing, multiple House members expressed dissatisfaction at FinCEN’s delayed implementation of the beneficial owner database, which was expected to be completed several months ago.

In his testimony, Das said that his office had asked for eighty new full time staff members who would be largely devoted to implementing the beneficial ownership database and other elements of last year’s legislation. These positions would include data specialists and outreach coordinators to help financial institutions and government agencies understand how to use the forthcoming data system.

In discussing staffing shortfalls, Das zeroed in on the problem of having too few analysts to track criminals using crypto currencies to covertly move money. “We continuously run up against challenges in terms of trying to figure out who is available to do work around crypto currency issues to be able to combat that illicit finance,” he said.

The Corporate Transparency Act contains loopholes pushed for by special interest groups that may blunt some of its power, even according to those who advocated for it and have celebrated its passage.

The ownership database will, for instance, not be publicly accessible. Only a subset of government and financial institution officers will be able to access ownership information contained in the new “secure, nonpublic database” that the law establishes. Researchers, journalists and others trying to track dark money will be shut out.

Still, advocates say they hope FinCEN will implement it smoothly, if not on time.

“Even with the resources we have and are using, we’re working full tilt,” Das told lawmakers Thursday. “But we need more.”