IMPACT

Clamor for crackdown on hidden wealth jolts Sri Lanka elite following Pandora Papers revelations

News of unexplained offshore wealth by members of the ruling Rajapaksa family has sparked a united call for government action in the economically-fragile country.

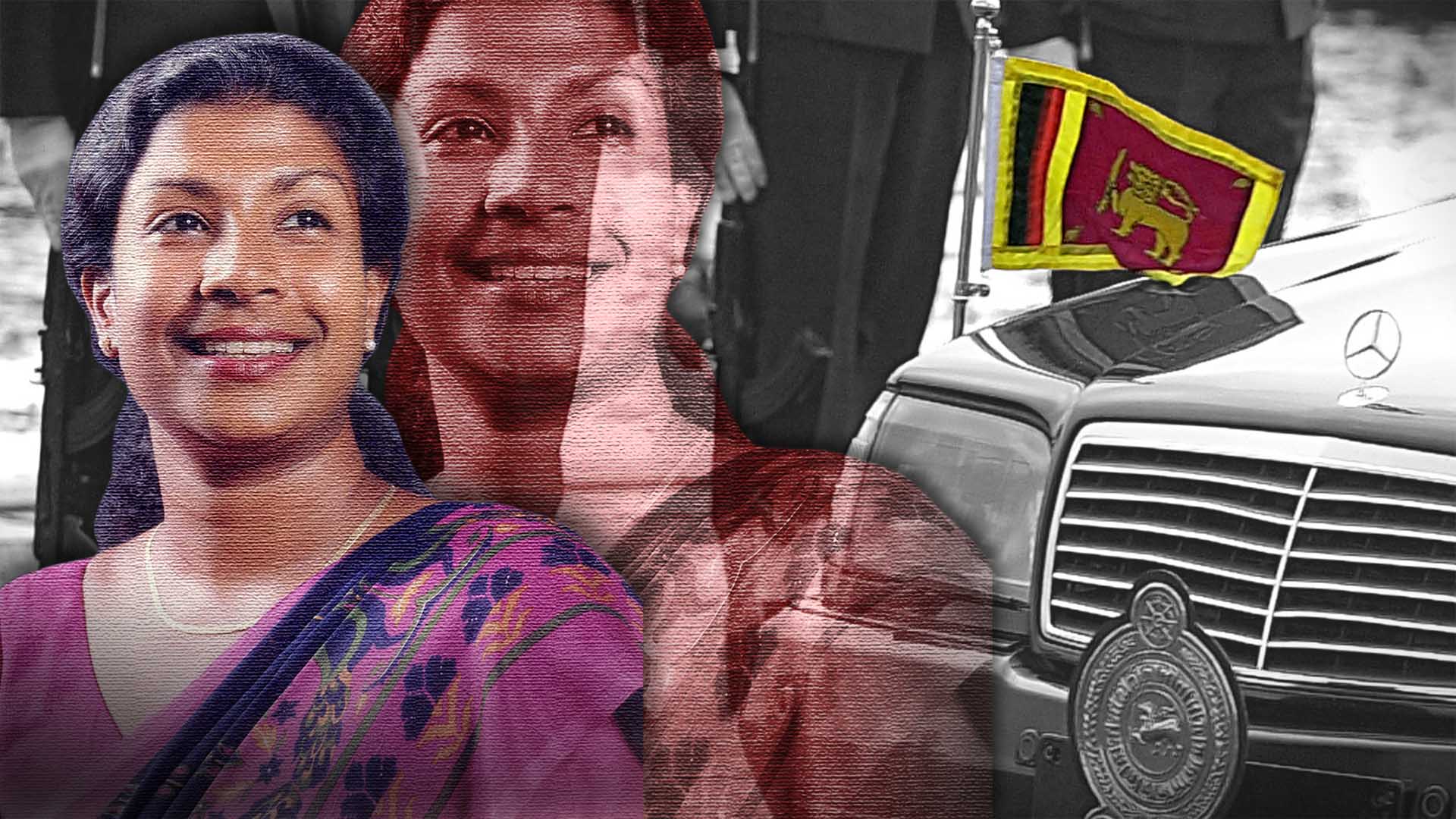

Anti-corruption advocates are demanding the Sri Lankan government take action after Pandora Papers exposed the hidden wealth of a former government official and a businessman tied to the ruling Rajapaksa family.

Activists from Transparency International Sri Lanka and others have made a united call for an investigation into the financial dealings of Nirupama Rajapaksa, a former deputy minister, and her husband, Thirukumar Nadesan.

Together, they have urged the Commission to Investigate Allegations of Bribery and Corruption and the country’s Financial Intelligence Unit to act after the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists reported how the couple held at least $17 million worth of assets in secretive offshore trusts. Nirupama Rajapaksa and Nadesan deny any wrongdoing.

The ICIJ investigation, based on a leak of 11.9 million, records also showed how Ramalingam Paskaralingam, a former adviser to three Sri Lankan leaders, created trusts and companies in the British Virgin Islands to hold millions of dollars, invest in a private college, and buy property in the U.K. Paskaralingam did not respond to ICIJ’s repeated comment requests.

Now in his 80s, Paskaraligam ー also known as “Paski” ー was more powerful than any minister during President Ranasinghe Premadasa’s government between 1988 and 1993, according to The Sunday Times, ICIJ’s partner in Sri Lanka. Even then, most large projects passed through him, the report said.

“The biggest revelation in the Pandora Papers … is the sheer magnitude of the facilitation architecture for capital flight,” a spokesperson for Transparency International Sri Lanka told ICIJ.

The investigation “comes at a time when the economy is doing very badly, resulting in severe hardships to the citizens,” the spokesperson said. “In this context, news of unexplained wealth held offshore hit close to home.”

Last month, Sri Lanka declared an economic emergency as food prices surged amid the fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic. Mounting foreign debt and an estimated 9% decline in tax revenue collection have beset the economically fragile nation, according to a 2021 report by the World Bank.

Despite that, the Sri Lankan government recently approved a controversial tax amnesty which would allow individuals with undisclosed assets and income to avoid penalties and prosecution if they disclose their wealth and pay 1% in taxes.

Transparency International advocates and a political group in the opposition have also requested government agencies to release Nirupama Rajapaksa’s asset declarations for the years she served as an elected official. Last month, the election commission notified the opposition group that it’s under consideration.

“We are acutely conscious that the actual amounts of wealth hidden offshore would be so much more than this [reported by ICIJ] – and it remains a massive problem for developing nations such as Sri Lanka,” the Transparency International Sri Lanka spokesperson said.

With the help of financial service providers in Singapore and other financial hubs, Rajapaksa and Nadesan bought luxury homes in London and Sydney, and artworks using shell companies in low or zero tax rate jurisdictions, the leaked records show.

In one document, Nadesan’s advisers noted that one of his entities’ source of funds was consultancy services for foreign companies doing business with the Sri Lankan government.

One of those companies, Japanese conglomerate Sumitomo Corp., denied its involvement with the contract listed in the document and with Nadesan or his companies, according to Kyodo News, an ICIJ partner in Tokyo.

Asiaciti Trust, a Singapore based provider, helped Nadesan manage his many shell companies and trusts, despite well publicized corruption allegations. In 2016, Sri Lankan authorities indicted Nadesan, alleging he had helped a former minister and member of the Rajapaka family build a luxury villa outside Colombo with public funds. Nadesan said the charges are politically motivated and the case is ongoing. The official, current finance minister Basil Rajapaksa, has denied wrongdoing.

Trident Trust, a British Virgin Islands based provider, helped Paskaralingam create two offshore trusts for him and his family even after a government commission in the late 1990s found he had abused his power and allegedly pocketed aid money. The Supreme Court later overturned those findings and he has denied wrongdoing.

In emailed statements to ICIJ, Asiaciti Trust and Trident Trust said that the firms comply with the laws of the jurisdictions where they operate.

In the aftermath of the Pandora Papers, President Gotabaya Rajapaksa ordered the Corruption Commission to investigate the ICIJ findings related to his relatives. Nadesan, who maintained his innocence, was reported to have testified twice before the commission, according to local media.

Still, anti-corruption watchdogs remain skeptical about the government’s true intentions.

“Investigations are a mechanism to suppress the truth and protect the guilty,” opposition politician Anura Dissanayake told the AFP news agency.

“The President referring the Pandora Papers to the Bribery and Corruption Commission (CIAOBC) and asking them to investigate the Sri Lankan involvement is tantamount to a bad joke,” says an editorial by the Sunday Times.

“The biggest prosecution it has done in all its years is arguably against a school principal who accepted a bribe of a tea set.”

In 2015, President Rajapaska himself came under fire over the Sri Lankan air force’s 2006 purchase of four second-hand MiG-27 aircraft from Ukraine, while he was the country’s defense secretary.

Sri Lankan journalists reported that Rajapaksa and a cousin allegedly used offshore accounts to purchase the fighter jets and pocketed about $10 million. Shortly after the “MiG deal” exposés, reporters were harassed and threatened. One was killed and his murder remains unresolved.

Gotabaya Rajapaksa was charged with corruption in 2016 over the deal. He denied wrongdoing and gained immunity after he was elected president in 2019. Last year, authorities arrested his cousin, Udayanga Weeratunga, former Sri Lanka ambassador to Russia, on money laundering charges. Weeratunga, who was later released on bail, has denied wrongdoing.

Advocates said that now is the moment for the Rajapaksa government to demonstrate a genuine commitment to accountability.

“Clear, consistent messaging would ensure that law enforcement authorities and the judiciary can carry out their roles without fear or favour, particularly given the close relationship of the individuals concerned to the President and the Prime Minister,” the Transparency International Sri Lanka spokesperson said.