Europe’s primary law enforcement agency has issued a report in response to the Pandora Papers that warns the scale of money laundering activities affecting the European Union has been underestimated, and calls for a coordinated approach to combat the illicit activities exposed by the investigation.

The report, titled Shadow Money: The International Networks of Illicit Finance, highlighted the “worrying” revelations in the Pandora Papers that hundreds of politicians were making use of offshore secrecy, alongside organized crime networks, terrorists, tax evaders and more.

“The Pandora Papers leak highlights the scope of financial crimes impacting on the EU. These types of financial offenses have been plaguing the EU and its many partners for decades without significant progress towards eradicating them,” the report said.

“The response to these challenges requires a two-fold approach – one based on policy and legislation as well as a strong integrated operational response driven by international cooperation.”

The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists’ Pandora Papers investigation revealed the secret offshore holdings of more than 330 politicians and 130 billionaires, as well as celebrities and royals. The files also shed light on the financial dealings of fraudsters, drug dealers, fugitive cult leaders and corrupt sports officials.

In the following interview with Pandora Papers partner and ICIJ member Kristof Clerix from Knack in Belgium, Europol director Catherine De Bolle expands on the Shadow Money report and the law enforcement agency’s focus on criminal networks making use of offshore secrecy.

—

Interview by Kristof Clerix (Knack, Belgium)

How is Europol tackling the Pandora Papers?

Catherine De Bolle: The publications are a source for Europol to update and feed our intelligence. We are not looking at it from a tax point of view but from the point of view of the fight against serious and organized crime. We note that criminals see the opportunity in these offshore destinations from the Pandora Papers, because there are few rules and little supervision. This is a parallel underground financial circuit. We have also noticed this in recent operations in which Europol took part.

In July 2020 the encrypted platform EncroChat was dismantled, in March 2021 the encrypted messaging service Sky ECC was taken down, and in June the FBI was able to intercept 27 million messages with its platform Anom – a honeypot for criminals. It is mainly on the basis of information from these three major operations that we find that we have a real problem in the EU. An example: when criminal groups launder money by buying real estate in certain European cities, this leads to undermining – the mixing of the legal upper world with the criminal underworld. And this undermining weakens society, the economy and the rule of law.

The Europol report states that the ‘scale and complexity of money laundering activities affecting the EU have previously been underestimated’.

De Bolle: Particularly worrying is the complexity of money laundering activities. In two out of three cases, money laundering occurs quite simply, through a direct investment in the legal economy. Think of hotels, restaurants, real estate, gold, luxury goods or art. But one in three money laundering operations are complex. That’s where we see these offshore locations popping up. For this purpose, criminal organizations hire money laundering experts who offer their services.

According to Europol, offshore providers – companies that help set up offshore constructions – are also a ‘key component’. Shouldn’t they be tackled harder?

De Bolle: That’s right. Of course we don’t go after rich families or companies that make use of offshore constructions. We really focus on serious and organized crime. Offshores offer criminals the opportunity to stay under the radar as the ultimate beneficial owner. All they have to do is pay to have everything set up by the offshore community. Then they get a company with articles of incorporation, nominee directors and the opportunity to become active in the legal economy.

Criminals will always look for loopholes in the system. It will be very difficult to close all loopholes worldwide. — Catherine De Bolle

As long as there is a single country that offers such financial secrecy, this offshore system will continue?

De Bolle: Criminals will always look for loopholes in the system. It will be very difficult to close all loopholes worldwide. But what we have to do in Europe is close as many doors as possible here.

What new money laundering trends has Europol identified?

De Bolle: We are seeing a steady increase in the number of cases involving cryptocurrencies, and expect this to continue in the future. That’s why Europol is investing enormously in training and expertise in that field. We are also working with the private financial sector to identify new developments. This could involve the virtual coins used by, for example, Chinese criminal groups.

According to the Europol report, no less than 7.5 trillion euro ($8.46 trillion) is held offshore globally.

De Bolle: That is, of course, an estimate. The European share of that is 1.5 trillion euro (about $1.69 trillion). And further, we know that tax evasion accounted for 46 billion euros ($51.9 billion) to the EU in 2016.

In October, the European Parliament in a resolution called on Europol to ‘step up its cooperation with Member States’ law-enforcement authorities in the context of investigations into tax crimes’.

De Bolle: It is important that there is an exchange of information between tax authorities and police authorities when it comes to crime. This should be done through the financial intelligence units in the EU member states. That sometimes happens already, but not always.

What has Europol actually done with the Papers and Leaks in recent years?

De Bolle: We only intervene when at least two member states are involved and when a member state requests our help. So far we haven’t received any questions from member states about the Pandora Papers. That’s normal, since financial investigations into organized crime are usually very complex and can take years. Only when member states have a basic case, they turn to Europol for our expertise.

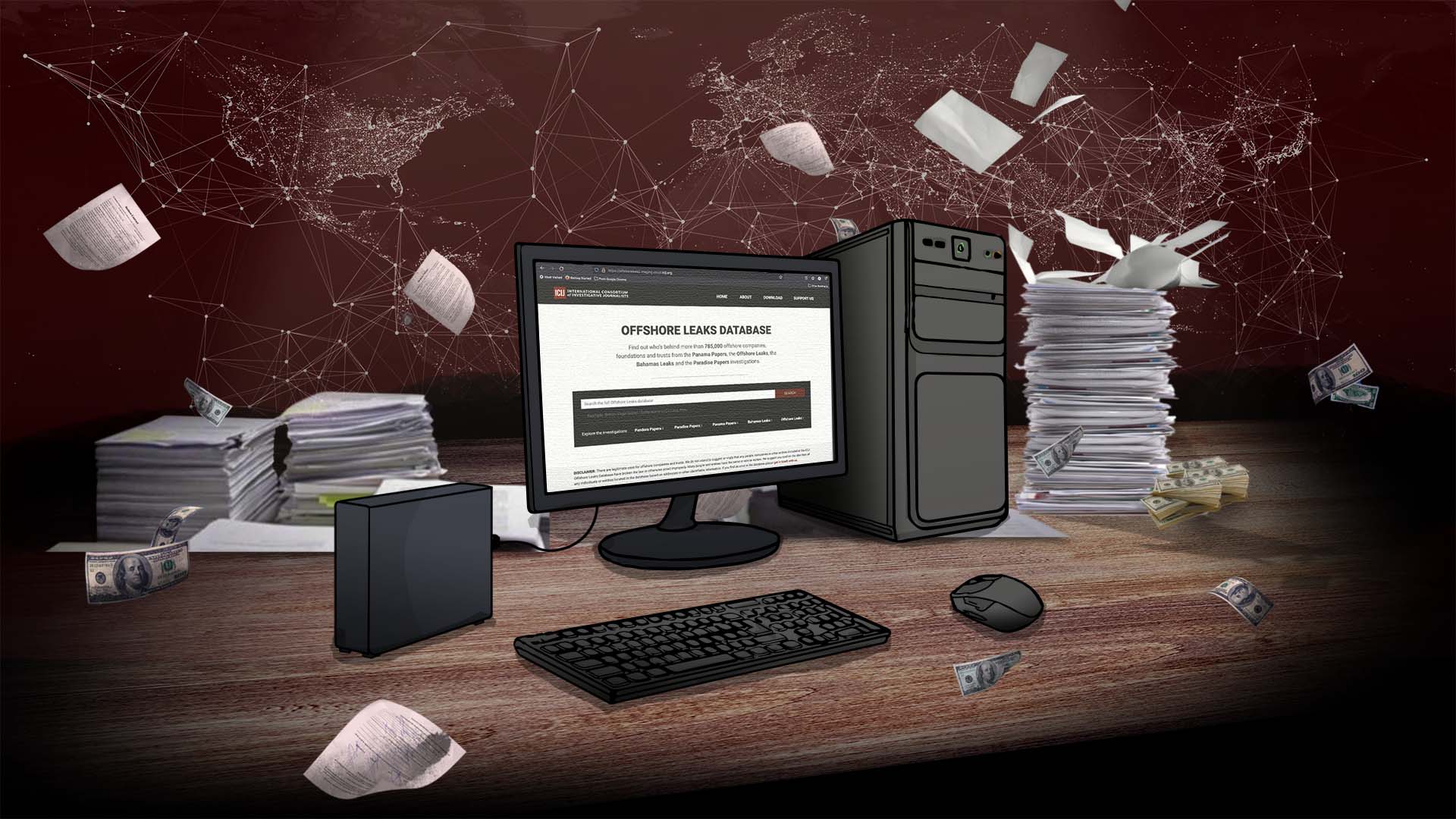

After the publication of the Panama Papers in 2016, ICIJ made a lot of information public. Based on that data, we found links to more than 20 EU member states and several Europol partner countries.

In the new report, Europol advocates focusing on asset recovery.

De Bolle: Confiscating drugs and bringing perpetrators to justice is not enough. You also have to go after the criminal assets. Yet not every investigation into organized crime is set up with a financial part. We advocate that member states make it a priority to freeze criminal assets.

Nice plan, but 98 percent of those criminal assets are never recovered in the EU.

De Bolle: That figure dates back to 2016, but there is no more current figure available and it is true that we are still not succeeding. Having said that, in the last three major operations, we did have a huge number of seizures. But the process from seizure to forfeiture takes a long time. It’s sometimes a matter of years. And yet asset freezing is so important.

When you take away a criminal organization’s assets, it has fewer options in the future?

De Bolle: Indeed. Precisely because all European countries recognize that there were too few financial and economic investigations, Europol set up a center of expertise in June last year: the European Financial and Economic Crime Centre (EFECC). This centre e.g. exchanges typologies and also promotes good practices. For example, there are some EU member states where assets can be forfeited even if you have not been convicted — at least if you cannot explain the origin of the funds. Such an administrative handling system could be considered by other member states as well. Because it strengthens confidence in the rule of law and belief in justice.