A coup in Gabon has marked the end of over half a century of unbroken dynastic rule during which the Bongo family accumulated enormous wealth both at home and offshore, as revealed by the Pandora Papers and several other investigations.

Soldiers seized power in the Central African nation last Wednesday, just hours after ailing president Ali Bongo was declared the winner of a disputed election. It was the third in which Bongo claimed victory — the previous two, in 2016 and 2009, were marred by violence and accusations of vote rigging.

Bongo was placed under house arrest and several of his close associates, including his son, Eton-educated Noureddin Bongo Valentin, were arrested for treason, embezzlement and corruption. The details of those charges remain unclear, but the Bongo regime has been labeled a kleptocracy by experts and advocacy groups throughout its existence.

A one-time musician, Ali Bongo came to power in 2009 after the death of his father Omar Bongo, whose nearly 42-year authoritarian rule was aided by his closeness to the former colonizer, France, and his use of Gabon’s petrodollars to build a network of patronage. Choice appointments such as cabinet positions went to trusted family members, and the father and son amassed vast wealth while presiding over a small population of 2.3 million.

Though Gabon is rich in oil and defined as a middle-income country, at least a third of the population is impoverished and unemployment is rife. Attempts to grow the middle class and diversify the economy had limited success, with oil accounting for around 70% of the country’s exports in 2020, according to the World Bank.

Amid a flagging economy, rising costs of living and growing inequality, a tiny elite connected to Bongo and his inner circle thrived as the growing wealth gap fueled popular resentment. The Bongos flaunted their status as one of Africa’s richest first families, maintaining fleets of luxury cars in a country with fewer miles of paved roads than of oil pipelines, and buying mansions in the United States and France. The popular term “Bongo system” came to describe this unbridled accumulation of wealth.

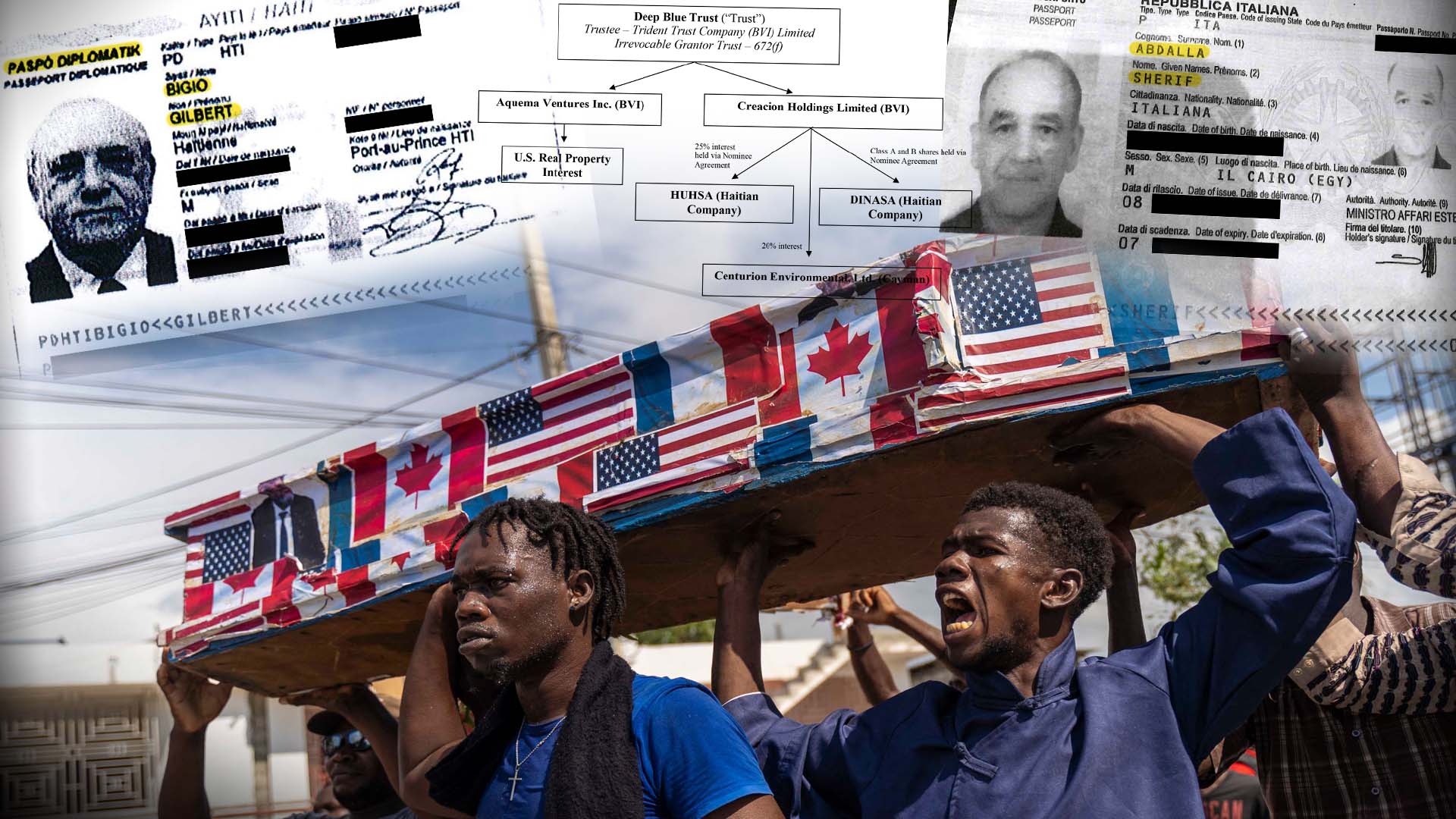

The family also funneled substantial wealth into offshore tax havens. ICIJ’s 2021 Pandora Papers investigation provided a glimpse into Ali Bongo’s offshore interests, revealing that he was the director of one shell company in the British Virgin Islands and that he held a stake in another BVI company alongside two political associates.

An email from 2008, when Bongo was Gabon’s minister of defense, noted that he was the major shareholder of Gazeebo Investments Ltd. and described him as a “civil servant.” The two associates were Jean-Pierre Oyiba, who was head of the presidential cabinet until 2009 when he resigned following a corruption scandal (he was not charged and denied wrongdoing), and Claude Sezalory, a Gabonese politician who was married to Sylvia Bongo Ondimba before she married Ali Bongo in 1989.

Bongo’s press office did not respond to ICIJ’s repeated requests for comment at the time of the investigation.

Much of the Bongos’ wealth was channeled into foreign properties. In a November 2020 report, OCCRP revealed that over the prior two decades the Bongos and their inner circle “purchased at least seven properties worth over US$4.2 million in and near the U.S. capital … .” Among those involved was the long-serving head of the constitutional court who was instrumental in helping the family hang onto power and is currently being detained under the coup. The report noted that “The Bongos’ Washington, D.C.-area homes were all purchased with cash.”

In the 1990s, investigators in the U.S. found that over $100 million had moved through U.S. bank accounts linked to Bongo senior.

The Bongos’ wealth has not escaped scrutiny in France, where probes that began under Omar Bongo’s presidency have strained relations between the former colonial power and the family it historically viewed as a reliable ally in Africa. A 2007 French police inquiry found that the family owned 39 properties and had 70 bank accounts. Faced with official reluctance to pursue the matter, civil society organizations, including Transparency International, went to court to force the French state’s hand, winning a precedent-setting case in 2010 in which the highest French court cleared the path for investigations against the ruling families of Gabon, Equatorial Guinea and the Republic of Congo.

The case led to the seizure of some Bongo family properties in 2016, including luxury mansions in Nice and Paris.

Last year, French authorities indicted several Bongo family members and associates, including at least nine half-brothers and sisters of Ali Bongo, for corruption, misappropriating public funds and money laundering. The 15-year-old case concerned alleged “undue commissions” paid by French energy company Elf and corrupt real estate transactions worth at least 85 million euros (about $94.6 million at the time of the indictment).

The last three years have been turbulent for several African countries whose governments have been toppled by coups: Niger, Burkina Faso, Sudan, Guinea and Mali. A failed coup attempt in Gabon in 2019, when Bongo was abroad for medical treatment, was a sign of things to come.

Coup leader Brice Clotaire Oligui Nguema, head of the Republican Guard, is now in charge of the country. His intervention ends the Bongos’ rule, but power remains within the elite and the extended family — Nguema is a distant cousin of Ali Bongo. He too was mentioned in the OCCRP report as having bought three properties in the U.S. for over $1 million, paid for in cash.

Since the coup, state television in Gabon has broadcast images of bags full of cash allegedly being seized from officials’ houses. Nguema, who was sworn in as the country’s new leader on Monday, had promised the military would return power to a civilian government, but did not want to “repeat past mistakes” by rushing the transition, according to reporting by Al Jazeera.