It wasn’t most 4-year-old girls’ idea of an ideal present.

In February 2008, golden-haired Happy received from her mother five books written by her father, James B. “Jim” Rogers, a U.S. billionaire investor, including one more than 430 pages long and another on how to invest in corn, cotton and coal.

“Adventure Capitalist: The Ultimate Investor’s Road Trip,” was one title in young Happy’s birthday bonanza. “Hot Commodities: How Anyone Can Invest Profitably in the World’s Best Market” was another.

Happy’s mother didn’t give copies of the books to the 4-year-old. What she did was transfer the ownership of the books’ copyrights to Happy and another daughter – still one month away from being born – known as “Baby Bee.” She did this via two offshore trusts, often hard-to-trace creations of a sort long regarded warily by tax authorities as smokescreens for hidden wealth and tax-avoidance schemes.

The gift was one of dozens of transactions used to fund seven trusts established for Jim Rogers’ wife and daughters and himself. Some trusts were structured “for tax purposes,” Rogers’ lawyer explained in 2013 to Asiaciti, a Singapore-based offshore services specialist.

Rogers did not respond to requests for comment. The trusts were declared to the Internal Revenue Service, Asiaciti’s files show.

In the years that followed, the trusts of Happy and Baby Bee received more than $100,000 in royalties from their father’s best-selling books.

By 2015, trusts worth more than $32 million had been established for family members by the adventurous Rogers, who is known as the “Indiana Jones of Finance” and holds Guinness World Records for globetrotting by motorcycle and by car.

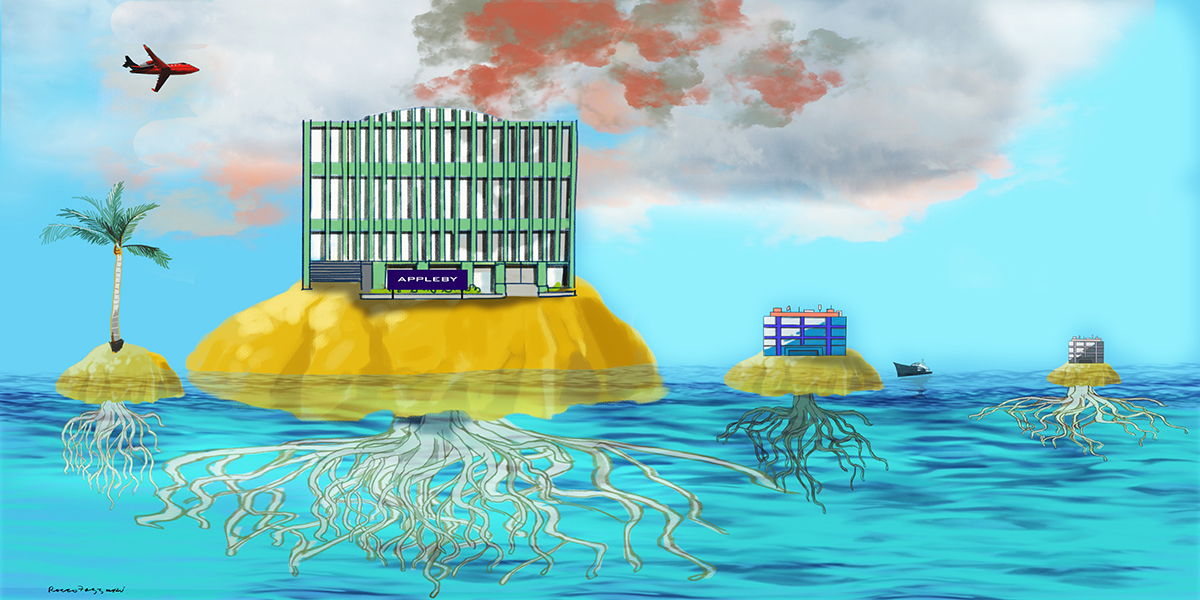

The leak of 556,000 files from Asiaciti passed largely unnoticed within the Paradise Papers, a trove of 13.4 million documents that reveal offshore secrets of politicians, celebrities, billionaires and companies whose brands are household names. Asiaciti’s emails, trust application forms, faxes and bank statements are vastly outnumbered by leaked documents from Appleby, a law firm and corporate services provider with offices around the globe.

Yet the files from Asiaciti – a trust specialist headquartered in Singapore, with branches in tax havens such as the Cook Islands and Samoa in the Pacific and Nevis in the Caribbean – shine a light on the practices of offshore clients ranging from the ultra-wealthy to the unremarkable, with a host of questionable clients in between.

Asiaciti did not respond to written questions, but issued a statement that it complies with applicable laws and regulations at all times.

“We are regulated by highly competent authorities in the jurisdictions in which we operate and are committed to achieving the standards required,” Asiaciti said. “We absolutely deny any implication of wrongdoing.”

In offshore trusts they trust

Founded in 1978 by Graeme Briggs, an Australian accountant, Asiaciti expanded throughout the 1980s and 1990s. It has described itself as “one of the leading offshore trust groups in the Asia-Pacific region.”

Asiaciti’s files reveal a significant American client base, including a California dentist, an Alabama grocer, a U.S. handgun and rifle manufacturer, and a food-truck entrepreneur from Los Angeles. Also found are Chinese millionaires and clients from Switzerland, Romania, Nigeria, Thailand and South Africa, in addition to an Israeli “branding” expert, an Egyptian gynecologist and a 26-year-old British eye serum and moisturizer salesman.

Asiaciti’s services range from tax, accounting and “wealth protection” services for individuals to secretarial services for global corporations. A major moneymaker is trusts.

I instinctively raise an eyebrow when I see a Cook Islands trust, because there are so few legitimate reasons for using such a trust, but many bad ones.

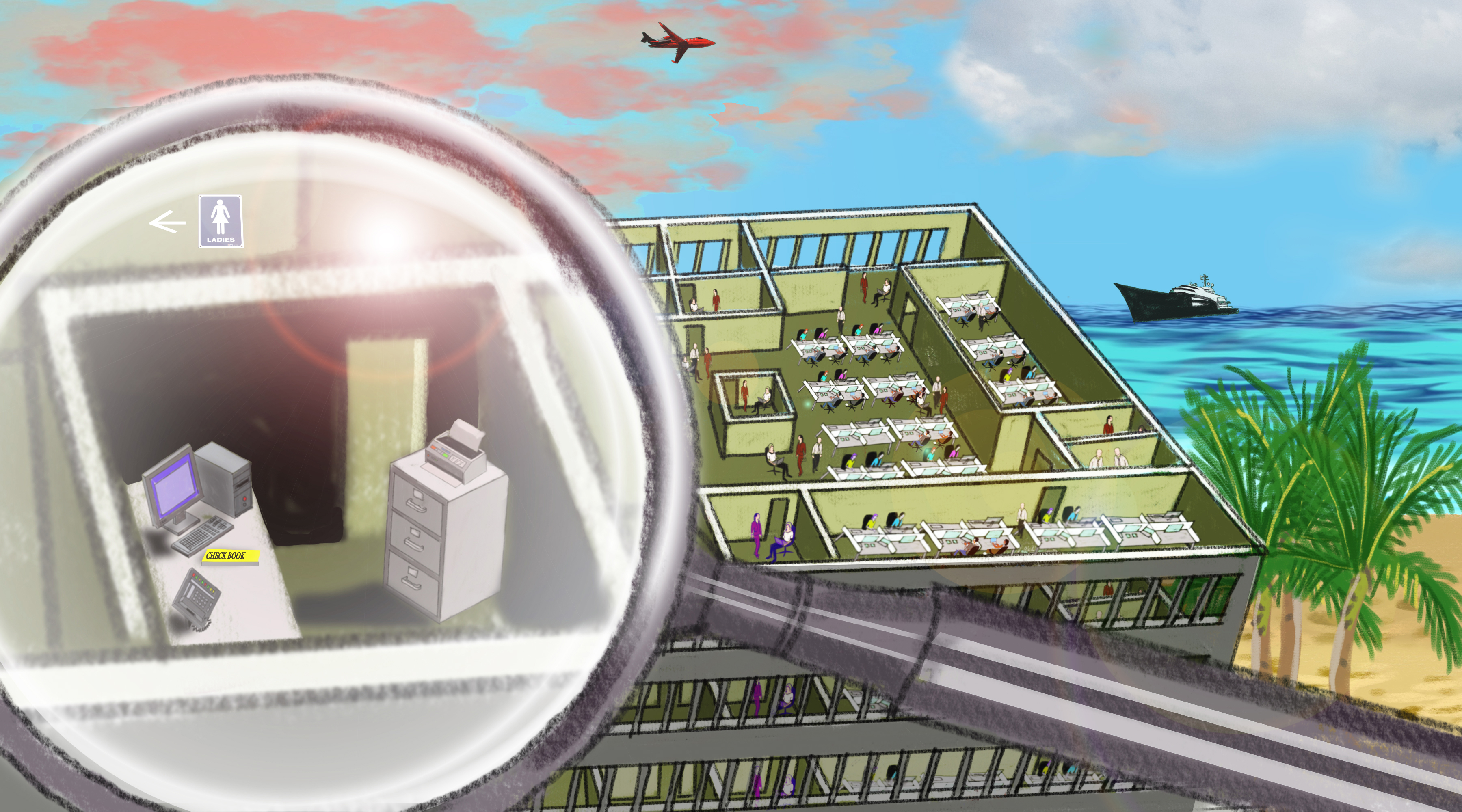

Offshore trusts are often inscrutable legal instruments with blurred official ownership. The details are rarely a matter of public record. Trusts allow the publicity-shy to act out of sight of creditors, ex-spouses or courts.

Asiaciti has specialized in establishing trusts in Samoa and the Cook Islands, nations of 200,000 and 11,000 people, respectively. Within 24 hours and for less than $300, a client could buy “ ‘state of the art’ offshore products” to build and preserve wealth, according to an archived version of Asiaciti’s website.

“The sad fact is that Cook Islands trusts are routinely used by people to cheat legitimate creditors,” said Jay Adkisson, an attorney and expert witness in a fraud case that involved Asiaciti’s trust division.

It’s difficult and expensive for creditors, attorneys or the tax office to access funds held by a client’s trust, Adkisson said. “They say ‘nyah nyah nyah nyah nyah, you can’t get it.’”

“I instinctively raise an eyebrow when I see a Cook Islands trust,” Adkisson said, “because there are so few legitimate reasons for using such a trust, but many bad ones.”

Global headaches

The leaked files reveal that authorities found omissions in Asiaciti’s records, including client records that lacked information necessary to combat money laundering and tax evasion. For example, an audit by the Cook Islands Financial Supervisory Commission in 2008 found a 33 percent level of compliance with regulatory standards.

“Grrr so annoying,” an employee at one Asiaciti office wrote about other Asiaciti offices whose incomplete files on four trusts were highlighted by a government audit.

Asiaciti’s clients included the family of Serik Burkitbayev, a former aide to Kazakhstan President Nursultan Nazarbayev and head of Kazakhstan’s state-owned oil and gas company. In March 2009, a Kazakh court convicted Burkitbayev of embezzlement – the theft of $20 million – and other crimes. Burkitbayev was sentenced to six years in prison, according to Kazakh news media.

By September 2012, as Burkitbayev languished behind bars, his wife and two daughters had set up three trusts in – according to the phrasing of one lawyer – “a small island nation named after an intrepid English sea captain whose surname rhymes with book.”

The Cook Islands trusts listed Burkitbayev as a beneficiary, meaning that he could eventually receive the offshore money. Asiaciti knew of Burkitbayev’s political past, but proceeded with the family’s business, according to emails sent in 2013. Emails from 2013 make no mention of his conviction.

The trusts would be funded with $2 million from a real estate deal and $6.6 million from the 2011 sale of one daughter’s interest in a former Soviet cluster bomb factory that was turned into a plant for the production of oil and gas cylinders, according to an email.

That plant, a leaked U.S. State Department cable said, was taken from a U.S. company by “politically influential” Kazakhs in late 2005. The Kazakhs “play dirty,” according to the cable, which reported that an assistant of Burkitbayev’s assailed the U.S. company with “what appeared to be an open threat to use political leverage.”

Under the 2011 sales agreement, shared with Asiaciti, Burkitbayev’s 29-year-old daughter and his former personal aide – the same assistant cited in the U.S. cable – owned about 77 percent of the Kazakh plant.

Asiaciti reviewed the documents and said it was “comfortable” proceeding with the trusts. They were closed in 2016. The Burkitbayev family did not reply to requests for comment.

Among Asiaciti’s other U.S. trust clients were Sean Novis and Gary Denkberg, marketing executives who targeted pensioners in a mail-fraud scheme, according to a civil complaint filed by the U.S. Justice Department. Novis, Denkberg and others told elderly victims that they had won more than $1 million and asked them to pay a fee – “generally in the range of $19.99 to $24.99” – to receive the prize, the 2016 civil complaint alleges. Victims often received nothing in return, according to the complaint. Over four years, the marketers and others allegedly pocketed more than $30 million.

Novis and Denkberg had one trust each with Asiaciti that at one stage held more than $1 million each, according to Asiaciti’s files. In February 2007, Novis asked the firm to help him find a bank that did not have “a presence in the USA.” Both men’s trusts were active in 2016 when Asiaciti learned of the civil case.

In 2016, a court imposed an injunction that prohibited Novis and Denkberg from mailing prize offers and sweepstakes in the United States. The Justice Department took no further action, a spokesman told ICIJ.

Denkberg told ICIJ that his trust was not involved in the civil case and that, to his knowledge, it had not held more than $1 million. The trust complied with the law and was declared to tax authorities, he said. Novis did not reply to requests for comment.

Gold and juice trader Sherman Unkefer III used his Cook Islands trust, called the Mango Trust and set up by Asiaciti, to “conceal his accumulated wealth,” according to a county prosecutor in Arizona who brought a civil racketeering claim in 2014. During and after his eight years in prison on a previous fraud conviction, Unkefer concealed assets to avoid repaying $18 million to more than 1,300 fraud victims, the prosecutor alleged.

Asiaciti was listed as a co-defendant in the case and was served with the complaint in the Cook Islands in June 2014, emails show.

The racketeering claim against Unkefer has been dropped, although alleged victims continue to seek compensation, a spokeswoman for the county prosecutor told ICIJ. Reached by phone, Unkefer’s partner said the couple had no comment.

The money in the Mango Trust was returned to the United States in 2014, said Michael FitzGibbons, the court-appointed officer who is seeking compensation for Unkefer’s victims.

“It was obvious they were trying to make his assets, if any, as unreachable as possible,” FitzGibbons said.