Jean-Claude Bastos de Morais was trying to invest offshore but was having a hard time finding a place to put his money.

The 50-year-old Swiss-Angolan financier turned to Appleby, an elite law firm with offices in tax havens around the globe.

First, Bastos tried Appleby’s office on the island of Jersey, a popular offshore financial center in the English Channel. But Appleby employees there balked at his 2011 request to set up a shell company without being told why it was needed or what assets it would hold. One thing that concerned Appleby’s Jersey lawyers was the possibility that the shell company would own a shipping port in corruption-prone Angola.

Next Bastos, an amateur tennis player who runs an asset-management firm, Quantum Global Group, tried Appleby’s office on the Isle of Man, in the Irish Sea. Appleby’s management there decided that Appleby would require a seat on the offshore company’s board of directors to exercise some supervision over what they described as his high-risk business. The arrangement did not go ahead.

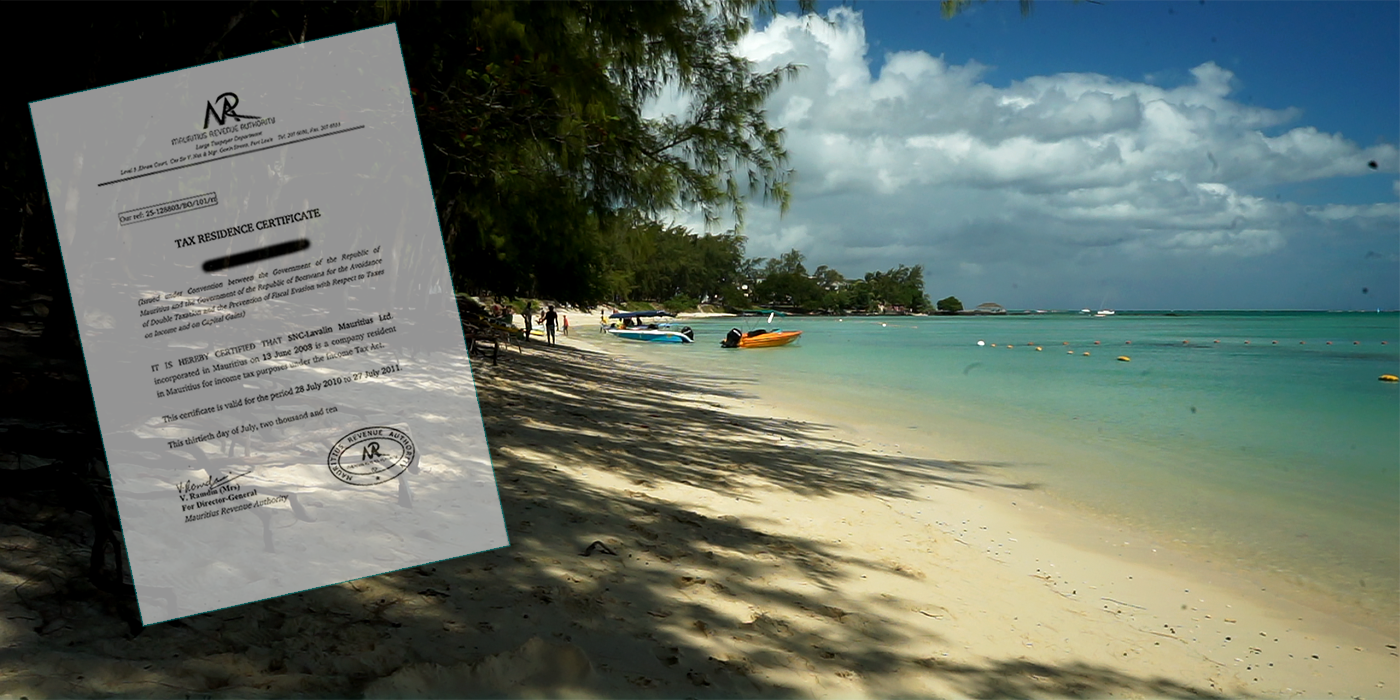

Finally, in 2013, after Angola’s sovereign wealth fund entrusted Bastos with $5 billion, he turned to another Appleby outpost: Mauritius, an island nation in the Indian Ocean, 1,200 miles off the east coast of southern Africa.

“We are pleased to be able to act on your behalf,” Appleby’s top lawyer in Mauritius, Malcolm Moller, wrote to Bastos’ Quantum Global in October 2013.

A window onto a tax haven

The warm email welcome for Bastos’ business is one of more than half a million secret records from Appleby’s Mauritius office that were obtained by the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung and shared with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and 94 media partners around the world. The Paradise Papers come from the offshore law firm Appleby and corporate services provider Estera, two businesses that operated together under the Appleby name until Estera became independent in 2016.

Some of the most important ways of stripping profits from African countries are done through offshore jurisdictions, including Mauritius. – Alexander Ezenagu

The emails, bank account applications, PowerPoint presentations on tax avoidance, and other confidential documents open a window into the operations of Appleby’s 40-plus-employee operation in Mauritius; By extension, they illuminate the surprising importance of Mauritius, an island nation with a multiethnic population of 1.3 million, as a hub in the secretive offshore financial network that enables legitimate, humdrum business to thrive but also helps wealthy people and profitable businesses shield their assets and profits from taxation.

Using an array of complex schemes and companies that are little more than addresses on a piece of paper, this global system has helped corporations shift $100 billion to $300 billion a year in tax revenue away from developing countries, according to the International Monetary Fund.

Offshore business transactions and the use of tax havens are often legal, but governments and representatives of civil society have increasingly criticized such behavior, which helps impoverish African governments and widen wealth inequality between the region and the rest of the world.

Research shows that companies are more likely to use questionable tax avoidance maneuvers when operating in developing countries than in wealthier countries where tax enforcement is stronger. African countries are vulnerable to tax avoidance and evasion because corporate taxes contribute more to Africa’s overall tax revenue, on a relative basis, than such taxes do for other countries.

“Some of the most important ways of stripping profits from African countries are done through offshore jurisdictions, including Mauritius,” said Alexander Ezenagu, an international tax researcher at the International Centre for Tax and Development.

Bastos and the Angolan fund

The Angolan sovereign wealth fund, Fundo Soberano de Angola, or FSDEA, manages $5 billion on behalf of a country where, despite its considerable oil wealth, one in three people lives in povertyand where corruption among government elites is perceived to be widespread.

Since its launch in 2012, the FSDEA has come under scrutiny because of its structure and concerns about how it is managed.

Its chairman, José Filomeno dos Santos, was appointed by his father, then president of Angola, José Eduardo dos Santos, who led the country from 1979 until this year. The younger Dos Santos’ appointment of Bastos, a personal friend, to manage the fund – which included billions of dollars set aside for investment in Africa and that would use companies in Mauritius – drew the attention of journalists.

In a statement to ICIJ, the FSDEA said, “Quantum Global was selected because of its exemplary performance on previous mandates with the Angolan authorities, its availability to carry out capacity building programs and commitment to develop a regional private equity management partnership with FSDEA.”

In a separate statement, Quantum Global denied that the relationship between Bastos and the Angolan president’s son influenced the FSDEA’s selection. Quantum Global told ICIJ that its selection was due to its “expertise investing in the continent” and its having outperformed other fund managers.

Appleby vets Bastos

The Appleby records show that the law firm did its own research on its new client. A compilation of internet search results compiled in January 2014 by an employee at Appleby’s Mauritius office included media references to lingering “questions” about how the fund would operate. The Appleby employee highlighted in yellow an article included in the search results that noted the “close personal” friendship between Bastos and dos Santos.

Appleby’s customer-screening process also flagged media accounts of Bastos’ past legal problems in Switzerland.

Records show that Appleby’s Mauritius office had classified Bastos as a “risky client ” but moved forward with its new business.

The first step was getting a coveted Mauritius business license. In a letter accompanying Quantum Global’s license application, Appleby’s Mauritius office told regulators that it had “made all reasonable enquiries” into Bastos, Quantum Global and their plans to manage the Angolan money.

On the application form – supplementing a question about whether any company director had been convicted, penalized or sanctioned in court – a summary was appended in which his personal lawyer disclosed that Bastos had paid a $5,390 fine after a Swiss court convicted him in 2011 of approving loans that he shouldn’t have.

Bastos’ lawyer, however, failed to mention that the Swiss court had also imposed a suspended fine of nearly $188,646. The application form also didn’t mention that the Swiss court also found Bastos guilty of withdrawing about $100,000 from a company account without authorization, according to a copy of the judgment obtained by ICIJ media partner SonntagsZeitung.

Bastos acknowledged the suspended fine but told ICIJ that the larger of the two fines did not have to be paid under a good conduct probation provision. Bastos said the suspended fine and convictions have since been expunged from Switzerland’s register of convictions. “The authorities were informed correctly,” Bastos said.

‘Please do not share’

With the license approved, Appleby’s Mauritius office helped Bastos and his company move some Angolan public funds slated for the management of investments in African hotels and infrastructure. The money moved through offshore companies in three jurisdictions – including some incorporated in Mauritius, known for its low taxes and high tolerance for secrecy.

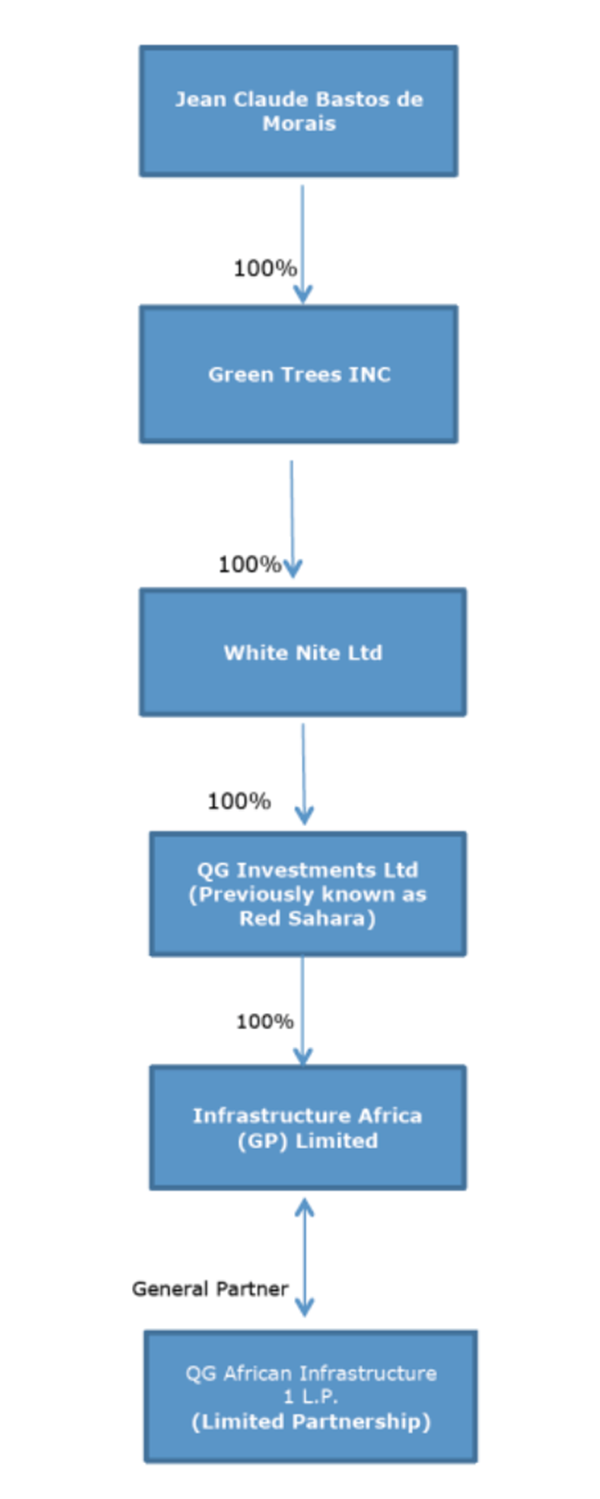

In an email sent to Appleby’s Mauritius employees to remind them of the sensitivity of their new client, Quantum Global’s lawyer wrote – in boldface type – that a British Virgin Islands company called Red Sahara Ltd. (later renamed QG Investments Ltd.), which would later receive tens of millions of dollars in dividends, was ultimately owned by Bastos. The information was “highly confidential,” the lawyer wrote. “That is to say, please do not share any information.”

The Angola fund once paid $20 million for shares in a company incorporated in the British Virgin Islands, Capoinvest, which was helping to finance the development of a major port in northern Angola. In its 2014 annual report, Angola’s sovereign wealth fund twice mentions Capoinvest, which also owns the Angolan company that is developing the port. There is no mention, however, of the additional offshore companies that own Capoinvest. Appleby’s files reveal it is owned by a chain of three companies incorporated in the British Virgin Islands and two more in the Seychelles, in the Indian Ocean, all of them ultimately owned by Bastos.

In his statement, Bastos said Quantum Global complies “in all countries with legal, tax and regulatory standards.”

He said, “I have routinely disclosed my shareholding in Capoinvest.”

Mauritius also provided a low-tax haven for substantial fees the Angolan fund paid Bastos’ operation. The financial statements of QG Investments Africa Management Ltd., Bastos’ Mauritius company, show it received $63.2 million in management fees throughout 2015, of which $21.9 million was sent to a Quantum Global company in Switzerland.

“The fees seem extraordinarily high,” said Andrew Bauer, an economic analyst and sovereign wealth fund expert who reviewed the fee payments.

Records show one Bastos-owned company paying dividends to another. In 2014 and 2015, QG Investments Africa Management paid $41 million in dividends to his QG Investments, based in the British Virgin Islands.

Bastos told ICIJ that Quantum Global was paid advisory fees “according to standard industry practices, all of which have been and continue to be fully disclosed.”

He said that “as any other shareholder, I am earning dividends out of the distributions of my companies.” He said his ownership of QG Investments Africa Management is tax-efficient.

Bastos declined to comment on “confidential business matters” that led him to approach Appleby offices in Jersey and the Isle of Man.

Bastos said Quantum Global chose Mauritius because of its its low taxes, “excellent infrastructure, relaxed reforms” and advantageous tax treaties, known as “double taxation agreements,” with most African countries.

An island on the rise

Mauritius is an island of white coral beaches and low mountains in the Indian Ocean. Colonized first by the Dutch, then the French and the English, Mauritius was for centuries used mostly to grow sugar cane, originally cultivated by slaves from the African region and Asia. The island diversified into textiles and tourism, but sugar held sway even after Mauritius, which is considered part of Africa, gained independence in 1968.

“Sugar was king,” said Hassen Auleear, 58, a cane farmer in northern Mauritius.

Auleear represents the third generation of his family to grow sugar cane – and his generation will be the last. Financial support for sugar farmers has dwindled, and every year, hundreds of them pack up and walk off land they have owned for decades.

Today, sugar accounts for just over 1 percent of the economy. Glass-clad towers in a suburb of the capital, Port Louis, house banks, accounting firms and law firms. The high-rises sit on what were once some of the country’s most fertile cane fields. And none of Auleear’s children intend to follow him into farming. Two of his daughters are accountants, one in Ebene CyberCity, the financial center.

Auleear said that the Mauritius government has abandoned sugar cane farmers and that the country looks down on those with dirt under their fingernails. “They think that people wearing a neck tie, a good shirt and shoes, sitting in an air-conditioned office is just fine,” Auleear said.

In 1989 the government embarked on a plan to turn the island into a hub for investment from all corners of the world. The island positioned itself as the “gateway to Africa” for foreign corporations, touting Africa as “an unfathomed mine of opportunities next door.”

The 1992 Mauritius Offshore Business Activities Act created corporate vehicles known as global business companies, which enabled non-Mauritians to incorporate there with little fuss and limited public disclosure. The island slashed its taxes and entered into tax treaties with neighboring African nations and others. The double taxation agreements (DTAs) were sold to treaty partners as a development tool that would encourage investment in those countries by the growing number of global companies incorporating in Mauritius.

In theory, DTAs are supposed to help companies avoid being taxed twice on the same economic activity. In practice, however, signing a DTA with a low or no-tax country such as Mauritius means that some taxes may not be applied at all. Businesses rushed to set up subsidiary companies in Mauritius and began to take advantage of tax treaties between Mauritius and other countries by channeling revenue through the island haven, a practice that has come to be known as “treaty shopping.”

By 2000, the country’s offshore financial industry had become, as described by the International Monetary Fund, “enormous.” Global businesses based on the island have assets valued at more than $630 billion, 50 times the amount of Mauritius’ gross domestic product. “Only Luxembourg has a bigger stock of foreign direct investment relative to the size of its economy,”according to the Financial Times.

In recent years, Mauritius’ African neighbors have complained that the island’s gains have come at their expense, and they have taken their case to the international community. In 2013, the U.N. Economic Commission on Africa criticized the island as “a relatively financially secretive conduit” that contributes to poverty on the continent. In 2015, the European Commission temporarily placed Mauritius on a top 30 blacklist of tax havens. Last year, Mauritius made nonprofit Oxfam’s list of the world’s 15 worst tax havens.

“While the full scale of tax losses from treaty shopping are shrouded in secrecy, countries in Africa are potentially losing a fortune,” said Attiya Waris, a tax law expert at the University of Nairobi.

Mauritius’s tax treaties withstood a landmark challenge in 2012 when India’s Supreme Court ruled that the Indian government couldn’t collect $2.2 billion from cell phone giant Vodafone’s purchase of an Indian operating company through offshore firms, including one in Mauritius. The way the purchase was structured had the effect of sidestepping Indian taxes.

Government agencies in Mauritius responded to ICIJ questions with an 11-page statement that denied that the island is a tax haven or secretive.

Where necessary, the agencies said, Mauritius will continue to enhance the country’s transparency and strengthen rules against tax evasion, terrorist financing, money laundering and corruption.

The agencies also said that no party to a treaty can impose conditions on the other and that a treaty is a “win-win situation” for both sides. Mauritius does not intentionally deny taxing rights to other African countries, the agencies said; some countries choose to forgo taxes to attract foreign investment.

Appleby’s ‘Africa Team’

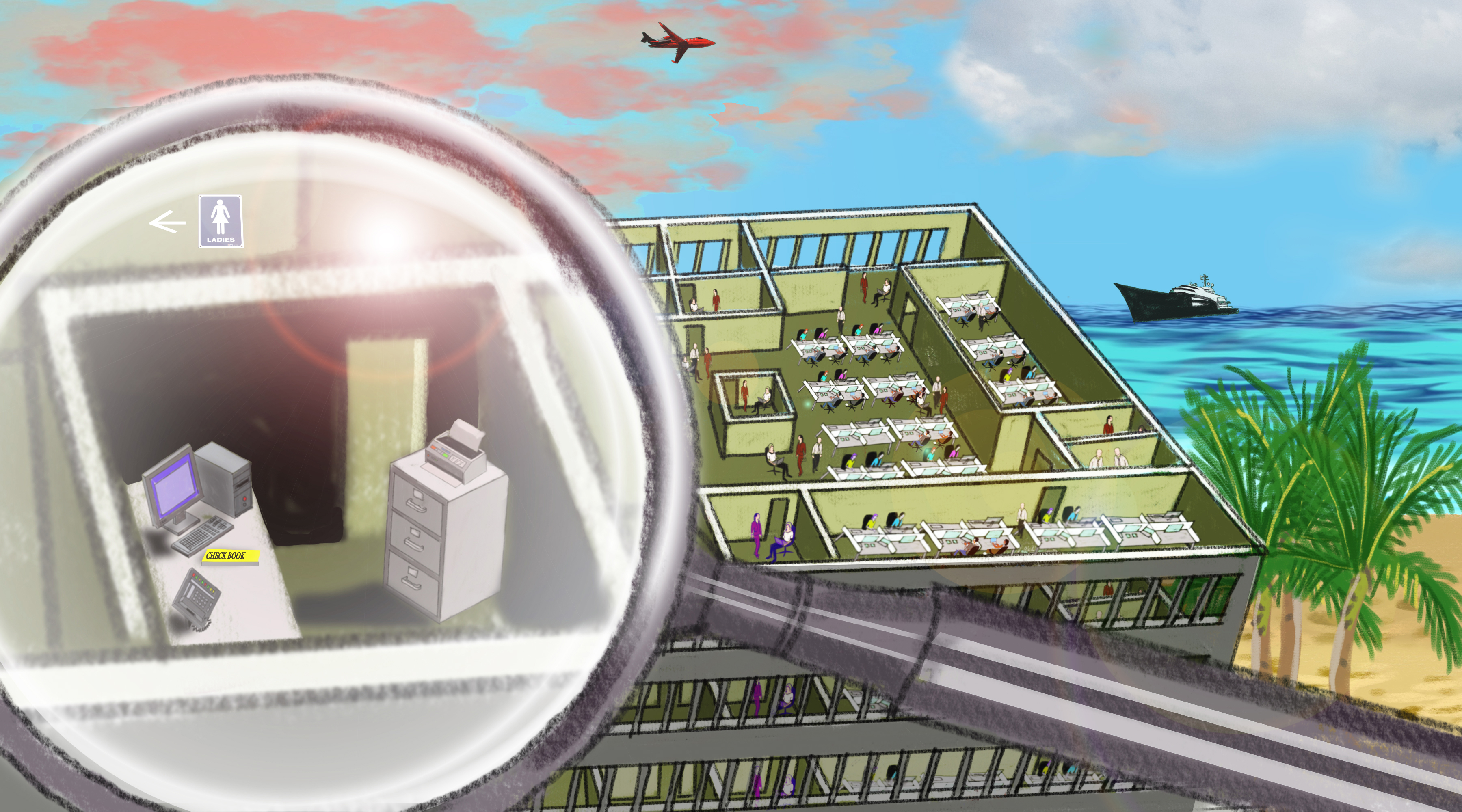

Appleby opened its doors in downtown Port Louis in 2007. The law firm occupies the top floors of a prominent building, above the busy shopfronts of modest clothing stores selling such items as Superman and Homer Simpson boxer shorts.

Secrecy on Mauritius is one of the office’s selling points. The Mauritius government maintains a corporate registry of more than 20,000 companies chartered on the island and keeps most information about them strictly confidential.

The leaked Appleby records show that the firm administered a trust fund worth more than $100 million for a European princess who told the firm that she would not send any emails and would keep calls to a minimum because, an internal memo said, “she did not want any trail.”

In April 2014, a South African-based investor, Luca Bechis, asked Appleby to create a Mauritius company that would buy mineral concentrate from mines in Mozambique. The plan was to send “any positive balance” offshore in the form of “consulting fees,” he said. Bechis told Appleby that he wanted to make sure that no tax would be paid in Mauritius – and that his name would not appear on corporate records. “I don’t want my involvement to be disclosed for privacy reasons,” Bechis wrote.

In an email, Bechis told ICIJ that Mauritius was one offshore alternative considered to hold mines across Africa and that it was legally vetted to comply with tax rules. Bechis said that the kidnapping risk faced by wealthy people and their families was behind his request for privacy.

From the start, Appleby’s Mauritius office has emphasized the services it offers to companies seeking to reduce or eliminate the tax burdens on their operations in Africa. Potential clients receive a full-color 50-page guide that extols Mauritius’ tax treaties. Thirteen of the 36 treaties on Appleby’s list are with African partners. Mauritius offers “an effective tax rate of 3% or… a tax liability of up to nil,” reads a typical marketing email Appleby sent to prospective clients. The office’s “Africa Team” has served corporate clients with business in South Africa, Togo, Mozambique, Madagascar, Kenya, Equatorial Guinea, Nigeria, Zimbabwe and Liberia.

In 2013, Appleby shared with another law firm a PowerPoint presentation about a hypothetical company operating in Mozambique with $10 million in interest payments due to be paid to its parent company in Singapore. If the money went from Mozambique directly to Singapore, the presentation explained, Mozambique would take $2 million in taxes. With the payments shunted through a company incorporated in Mauritius, however, a treaty between the two countries would slash the tax owed Mozambique by more than half. Mozambique receives $800,000, and the company, assuming the operation in Mauritius costs $30,000, saves $1.17 million.

Countries are giving up “5, 10 or 15 percent of revenue from a deal. That’s a very significant amount of money,” said Catherine Ngina Mutava, associate director of the Strathmore Tax Research Centre at Strathmore Law School in Nairobi, Kenya. For officials in Mauritius, Mutava said, “ultimately … their state comes first, even if it means that other African countries suffer in the process.

A Namibian fish tale

In 2012, Pacific Andes Resources Development Ltd., one of the world’s biggest producers of fish oil and fish meal, moved into the lucrative Namibian horse mackerel market. The bluish-green or gray fish is so important to Namibia’s identity and economy that the country’s 5-cent coin features an engraving of one over the injunction: “HORSE MACKEREL: EAT MORE FISH.”

The company had come under scrutiny before arriving in Namibia. Since the early 2000s, reports by experts, international organizations and tribunals had alleged that Pacific Andes was operating an illegal fishing ring in the Pacific Ocean. A 2002 report by members of the fishing industry alleged that Pacific Andes used unlicensed boats to poach fish near Antarctica “on a scale never seen before.” Pacific Andes denied wrongdoing. The company told ICIJ that it improved internal controls to comply with sustainability and health requirements.

Pacific Andes had made powerful friends inside Namibia and partnered with a local operation, Atlantic Pacific Fishing (Pty) Ltd. to catch the mackerel. Atlantic Pacific Fishing was no ordinary company; documents obtained by The Namibian newspaper and shared with ICIJ reveal that its directors included Namibia’s deputy minister of lands, deputy secretary of higher education, a former capital city mayor, as well as advisers to Namibia’s prime minister and president.

In 2012, Appleby did its part by helping Pacific Andes, headquartered in Bermuda, set up a subsidiary in Mauritius. The new company, Brandberg (Mauritius) Investment Holdings Ltd., received a government-issued tax certificate the same year that would allow the company to benefit from the two countries’ double taxation agreement. Under the treaty, the company could potentially cut some future tax payments in half. Pacific Andes conducted much of its business in Mauritius and Namibia through a subsidiary in the Cayman Islands, China Fishery Group Ltd.

Files from Appleby’s Mauritius office and court documents obtained by ICIJ show that Pacific Andes used several offshore companies, including a Mauritius company – Brandberg, which had no employees – to direct fees and payments from high-tax Namibia into low-tax jurisdictions.

In August 2013, for instance, a company in the British Virgin Islands leased a fishing boat to Brandberg in Mauritius for $31,700 a day. Brandberg then chartered the boat, named Sheriff, to Atlantic Pacific Fishing in Namibia. Later that year, Brandberg and Atlantic Pacific Fishing signed a contract under which Brandberg managed the Namibian company’s ships, employees and mackerel trade in exchange for a management fee of 4 percent of the value of fish sales.

Atlantic Pacific Fishing paid $1.25 million in boat chartering fees to Brandberg in Mauritius over more than two years, according to Atlantic Pacific Fishing’s 2015 annual report, obtained by The Namibian newspaper. Annual reports also show that the Namibian company paid nearly $2 million in management fees to Brandberg between 2013 and 2014 and owed the Mauritius company outstanding bills totaling more than $8 million. All of it was purportedly earned by a Mauritius company with no office of its own.

Alexander Ezenagu, an international tax researcher, said payments to a shell company in Mauritius could significantly reduce the amount of money that a company like Atlantic Pacific Fishing has to pay taxes on in Namibia. “The structures are geared at stripping profits” from high-tax jurisdictions, he said.

In response to ICIJ questions, Pacific Andes said Namibian shareholders received more than four times the value of management fees paid to the Mauritius company and the majority of fees stayed in Namibia as working capital. Atlantic Pacific Fishing also employed more than 100 Namibians, Pacific Andes said.

In 2016, the Pacific Andes subsidiary, and Brandberg’s owner, China Fishery, filed for bankruptcy protection in New York. A court-appointed trustee is trying to collect millions of dollars to restructure the company and repay China Fishery’s debts.

This year, the trustee told the court that he had a “high degree of concern” about the company’s accounting practices. The trustee found one entry of $18.8 million listed in a subsidiary company’s accounts but could find no evidence that the purported sale accounting for the entry ever took place.

The trustee put Sheriff, the fishing boat, up for sale.

Pacific Andes said it had clarified and resolved the $18.8 million accounting entry with the trustee.

Band-aid solutions

After years of bad publicity and some behind-the-scenes diplomacy, Mauritius has taken steps to reform its offshore sector. To discourage misuse of offshore companies, authorities introduced requirements that such companies become more active in Mauritius – which would include having employees and meetings there. In July, Mauritius signed a global anti-tax-avoidance treatyand agreed to review half of its double taxation agreements.

Jean-Claude Bastos and his company were aware of African countries’ growing intolerance of Mauritius’ letterbox companies and sensed the shift in the public mood in Africa.

When Bastos’ Swiss asset-management company was considering options to avoid taxes in countries where the sovereign wealth fund might invest , a lawyer for Quantum Global wrote to a tax accountant in 2014 about where one of the employees would work. “We understand that it certainly looks better to have the Manager in Mauritius,” the lawyer wrote. “But, we are pushing back here.”

The email suggested that the company was willing to take its chances. If other countries objected to Quantum Global’s use of Mauritius to reduce its tax bills across Africa, the letter said, it would deal with the problem “when the time comes.”

Critics remain skeptical of Mauritius’ reform efforts. The country rejected major elements of the global anti-tax-avoidance treaty, including an amendment that would have allowed African countries to collect more taxes when corporations bought and sold land through Mauritian companies. Mauritius chose to renegotiate some double taxation agreements, particularly those with other African countries, on a one-on-one basis instead of through the global treaty.

The new global rules might “kill a few of the problematic elements, but it won’t really change anything in the near future for most African countries,” the Strathmore Tax Research Centre’s Catherine Mutava said. “It’s like putting a Band-Aid on a huge leak. I don’t see anything changing soon.”

Contributors to this story: Christian Brönnimann and Shinovene Immanuel.