PARADISE PAPERS

Trust company fined $835,000 for opening ‘gateway to possible money laundering’ in Angola

An investment scheme involving tycoon Jean-Claude Bastos de Morais exposed in ICIJ’s Paradise Papers investigation bore “obvious” risks of possible corruption, a Jersey court finds.

A court in the Channel Islands has fined a team of accountants and economists who for years ignored “obvious” risks of possible corruption and embezzlement when providing services to an investment management company working with the government of Angola.

In a decision published this week, Jersey’s Royal Court fined LGL Trustees Ltd more than $835,000 for two breaches of the island’s anti-money laundering laws. LGL Trustees pleaded guilty in December.

From 2010 to 2016, according to the judgment, LGL pocketed more than $1 million in fees providing services connected to the management of Angola’s sovereign wealth fund, whose investments were overseen by Jean-Claude Bastos de Morais. Despite questionable and what the prosecution called “colossal” fees paid to Bastos, the reluctance of banks to deal with him, and concerns over a prior conviction, the trust company “effectively opened the gateway to possible money-laundering” in accepting the work, the court decision said.

Bastos is a close friend of José Filomeno “Zénu” dos Santos, who was appointed by his father, then president of Angola, to manage the country’s sovereign wealth fund. Bastos and dos Santos were arrested in 2018 on suspicion of embezzlement. Bastos denied wrongdoing and reached a settlement with Angolan authorities. Zénu was sentenced to five years in jail for an unrelated fraud case.

In 2017, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, the BBC and Tages Anzeiger revealed Bastos’ personal windfall as part of the Paradise Papers investigation. Bastos received more than $41 million in dividends in 20 months, according to leaked financial records. Experts told the BBC that the arrangement to manage Angola’s sovereign wealth fund was “unusual.”

Attorneys for Bastos told ICIJ that the Jersey case “involved no findings that any crime had been committed, by anyone,” including Bastos and his company, Quantum Global. The attorneys pointed to a 2018 court decision in England that dismissed claims made by Angola’s sovereign wealth fund against Bastos and Quantum Global, and that found “no evidence” of abnormal or illegitimate structures or business purposes. Quantum was subject to “significant due diligence” by an independent property firm and created “hundreds of millions of dollars of profit” for Angola, attorneys at Grosvenor Law told ICIJ.

In its decision made public this week, Jersey’s Royal Court said that while Angola’s wealth fund and investments were not in themselves suspicious, LGL’s “ineffective” approach missed red flags. The firm “took the risk of being involved in the diversion of tens of millions of dollars of public funds of one of the poorest countries in the world to its corrupt rulers, and their relatives and associates,” prosecutors said.

St. Helier-based financial regulation expert Mathew Beale told ICIJ that, on the face of it, LGL’s position was both “embarrassing” and “a shocking position to be in.”

Beale told ICIJ that he expects to see more such cases emerge in Jersey. “In the good old days, the perception was that an offshore center would publish itself by palm trees and beaches and the occasional bikinis,” Beale said. “Jersey markets itself as an international financial center that is a tough place to do business and if you do it badly, you’ll get in trouble.”

Red flags and huge fees

In April 2010, a Jersey law firm asked LGL to “establish and administer” a limited partnership on behalf of the government of Angola, according to the court’s summary of the facts of the case. Bastos, through his company Quantum Global, would manage the Jersey partnership, according to the plan.

The firm rated the new business as “very high risk” and even met with Jersey’s regulator to discuss the matter. It created the partnership and two Jersey companies for Quantum Global.

From the very beginning, Jersey prosecutors argued, “there were numerous ‘red flags’ that the investment scheme might well be a fraudulent scheme to skim funds from Angola’s public treasury and re-route them to the notoriously corrupt Angolan president and/or his relatives and associates.”

One cause for alarm were the “colossal” fees that Bastos received in exchange for little work, according to Jersey prosecutors. The deal included an almost $20 million advance payment and guaranteed Bastos’ Quantum Global $40 million a year even if the investment flopped, according to the court.

“It should have been a source of obvious concern that millions of dollars of the public funds of a very poor country were being paid by means of these fee arrangements to a third party connected to the Angolan presidential family for no obvious good reason,” the prosecution said.

LGL also knew that global banking giant HSBC had refused to open an account for Bastos due to media reports in 2011 that raised the possibility of corruption. The bank told LGL that it was concerned that management fees could be “diverted back to senior figures in Angola,” according to notes taken by LGL.

LGL visited Bastos in Switzerland, where the businessman denied the allegations. LGL “simply carried on with the business, apparently satisfied by Bastos’ denials,” according to the judgment.

Quantum Global ultimately opened an account with Standard Bank. The bank did not reply to ICIJ’s questions.

A second red flag came when LGL learned that Bastos had been convicted in Switzerland in 2011 of “repeated qualified criminal mismanagement.” LGL closed its inquiries about the conviction after reassurances from Quantum Global. There was no evidence that LGL asked why Bastos failed to disclose his conviction and LGL never told Jersey regulators about the criminal conviction, the court wrote.

“It seemed that nothing would dissuade the directors from accepting and maintaining this business, despite the negative publicity,” a former LGL employee was quoted as saying in court documents when her supervisor overruled her recommendation to reject Bastos’ business.

A spokesperson for LGL told ICIJ that the charges concern policies and procedures applied to “a single client on-boarded over 10 years ago.”

“While the group had policies and procedures in place, LGL accepted that these were insufficient when applied to this specific client. There is no suggestion that either LGL or this client was involved in money laundering, or that any party suffered financial losses as a result. Since the events of 10 years ago, LGL has a new senior management team in place with enhanced controls across the business. LGL is committed to upholding the highest standards, in accordance with regulations in all of our jurisdictions.”

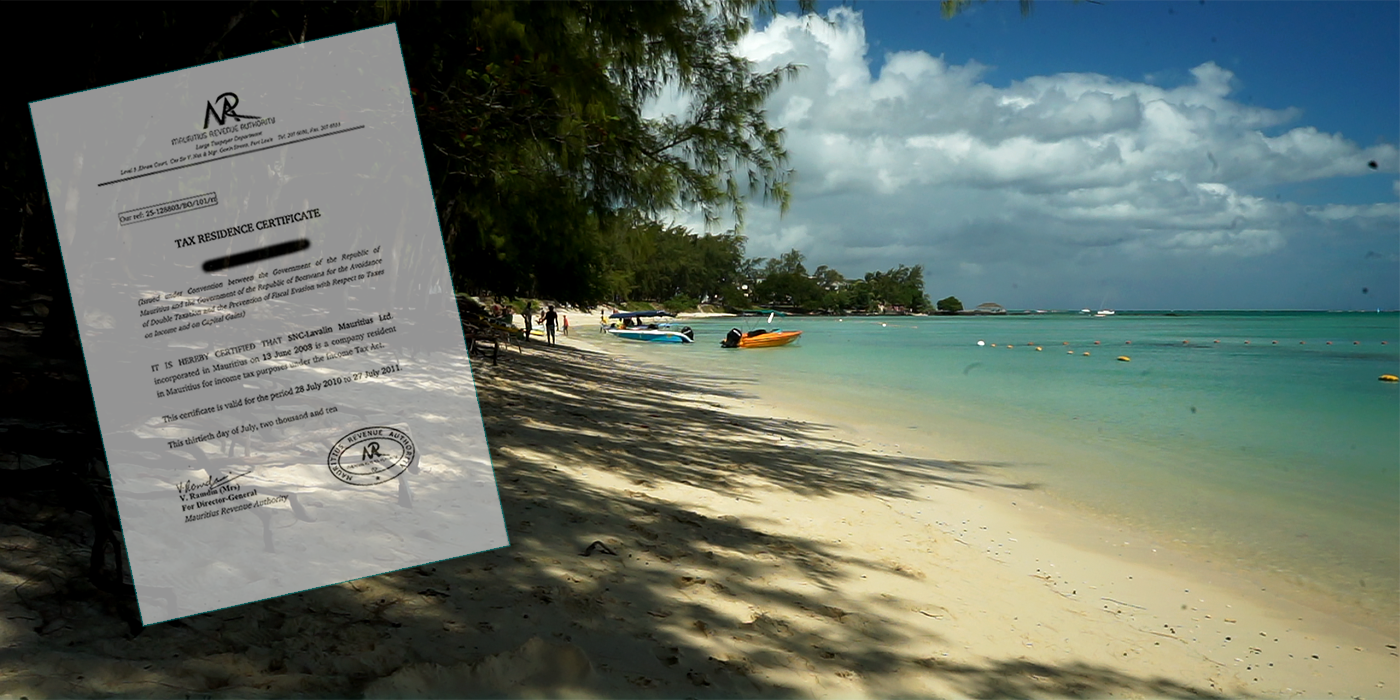

Tax haven hopping to Mauritius

As part of the Paradise Papers investigation, ICIJ and media partners revealed that the law firm Appleby rejected Bastos and Quantum Global’s business pitch in 2011. Appleby’s Jersey office balked at possible corruption, according to internal emails obtained by Süddeuteche Zeitung and shared with ICIJ.

Bastos pivoted elsewhere and contacted Appleby’s office in the African tax haven of Mauritius, ICIJ reported. The Mauritius office accepted the business. In 2018, following publication of the Paradise Papers findings, Mauritius suspended Quantum Global’s license to operate on the island.

Appleby’s Mauritius office did not reply to questions about why it accepted Bastos’ business.

A spokeswoman for Mauritius’ Independent Commission Against Corruption told ICIJ that the agency opened an investigation in November 2017 after the Paradise Papers investigation. Angola was “reluctant to make a formal complaint despite several requests made” by Mauritius, ICAC told ICIJ.

The office said it closed its probe after Quantum Global returned assets to Angola and after freezing orders imposed by regulators in Mauritius were lifted on Bastos and Quantum Global’s bank accounts and operating licenses.

Jersey-based Beale says that Mauritius hasn’t shown the same level of enforcement as Jersey.

“My message to Mauritius is don’t paint over the cracks,” Beale said.