No one ever wants to go to the hole. And for good reason.

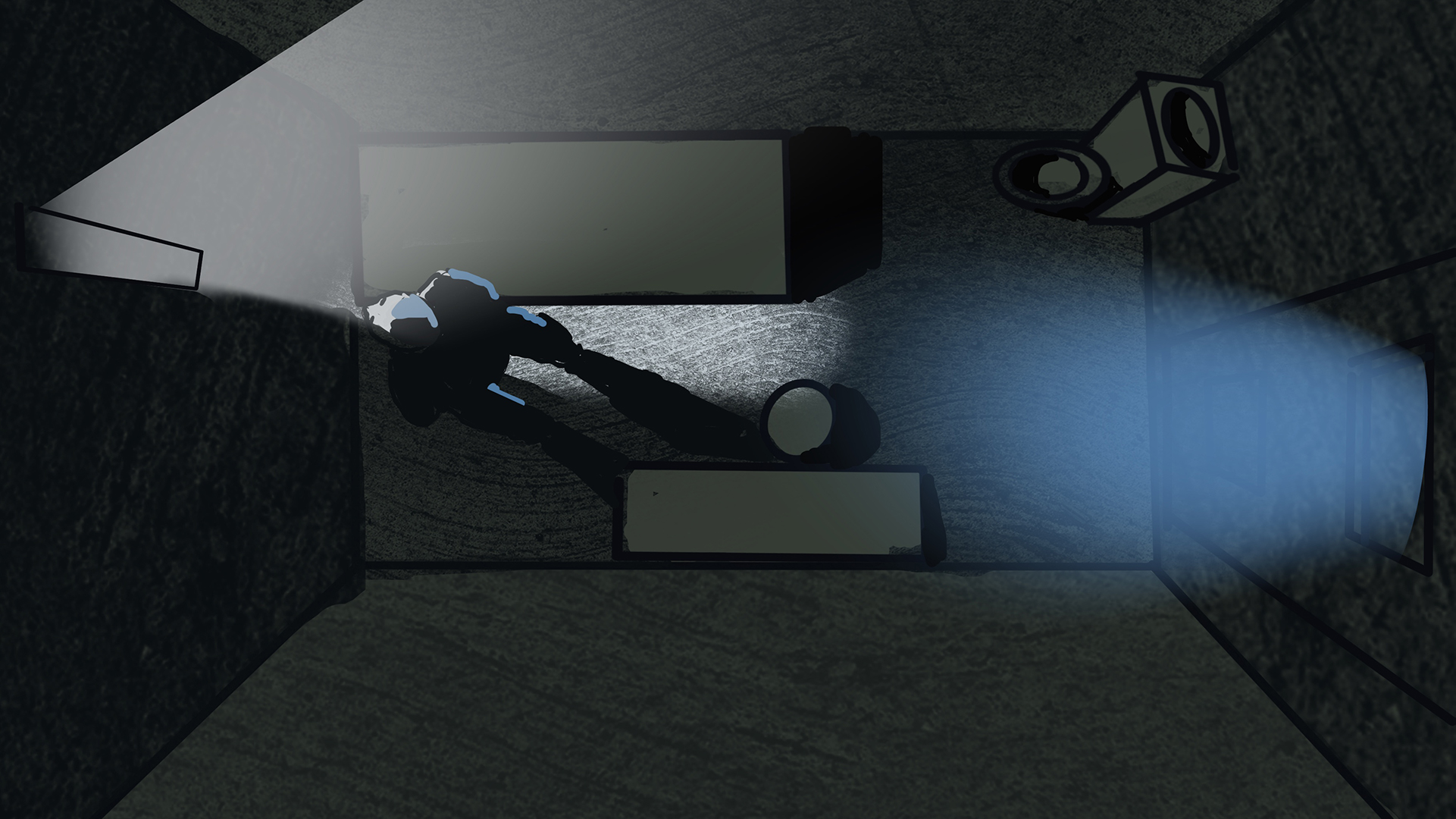

Solitary confinement — typically 22 to 24 hours a day locked alone in a tiny cell, with little opportunity for meaningful human interaction — is lonely and boring, and it can lead to extreme mental and emotional distress. Sleeplessness, chronic depression, hallucinations and suicidal impulses are possible side effects.

Solitary confinement is most often associated with prisons for people convicted of crimes. But it has also become a go-to tool to manage the swelling number of people held by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement in detention centers across the United States, an investigation by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and its partners in Mexico, Guatemala, the Dominican Republic and the U.S. found.

Here’s a short guide to what we learned about solitary confinement and its use by U.S. immigration officials.

For starters, what is ICE?

The U.S. Homeland Security Department’s Immigration and Customs Enforcement unit is the federal agency primarily responsible for enforcing U.S. immigration law. It has a $6 billion budget and more than 20,000 law enforcement agents and support personnel. As one of the agencies tasked with carrying out President Donald Trump’s hugely controversial — and now suspended — family separation policy, it also has become the focus of global condemnation.

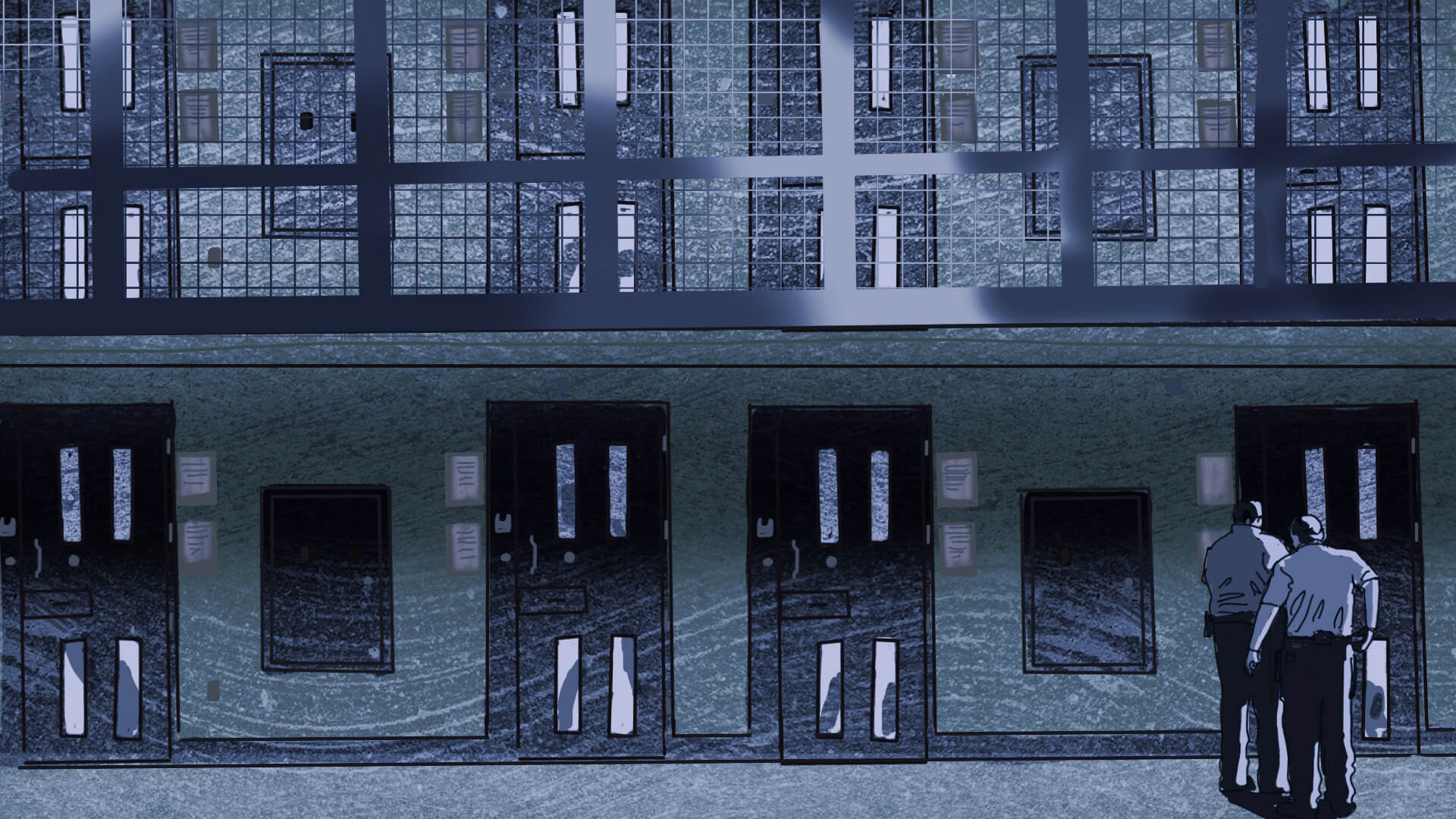

The agency relies on a sprawling network of more than 200 detention centers that as of April held about 50,000 immigrant detainees. Many of these centers are run by private contractors or are situated in jails or prisons.

And what is solitary confinement?

The U.N.’s special rapporteur on torture has described solitary confinement as the isolation of someone for 22 hours or more a day without meaningful human contact.

Access to phones, visitation, commissary, daily activities and other programming is often significantly curtailed. Detainees are often placed in handcuffs when escorted outside their cells to shower or for severely limited periods of outdoor recreation.

Inside ICE facilities, solitary confinement is typically referred to as segregation, “the hole” or SHU, for special housing unit.

Who does ICE place in solitary confinement?

They are non-U.S. citizens who have been apprehended and put into the civil immigration detention system. An ICIJ analysis of more than 8,400 incident reports describing solitary stays from 2012 to early 2017, found that the nationality of detainees held in solitary broadly reflects overall immigration trends.

More than half of the records describe the confinement of citizens of Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras. Overall, though, it is a remarkably diverse group, with more than160 nations represented, including India, Iraq and China. Nearly 95 percent of the detainees were men. Less than 10 percent were represented by an attorney.

Why would ICE isolate a detainee?

The agency’s detention standards allow it to use solitary confinement for a variety of reasons, including as punishment for bad behavior and to segregate those who might be at risk of harm in the general population. In many cases, ICE policy dictates that segregation be used as a last resort, only if other options aren’t feasible.

In the records reviewed by ICIJ, disciplinary segregation was the reason most often given for placing a detainee in isolation, with such incidents making up nearly 42 percent of all stays.

How is solitary confinement actually used?

In Solitary Voices, ICIJ and its partners found that U.S. immigration officials have repeatedly used isolation to segregate some of the most vulnerable detainees for weeks and even months.

In nearly a third of the placements reviewed by ICIJ, the detainee had a mental illness — a condition the U.N. considers an immediate disqualifier for solitary confinement. Records reviewed by ICIJ describe detainees with mental illness mutilating their genitals, gouging their eyes, cutting their wrists and smearing their cells with feces while in isolation.

Hunger strikers, people who identify as transgender and suicidal people have all been held in solitary confinement for extended periods against their will, ICIJ found.

Sometimes ICE facilities appear to use solitary to house detainees they simply don’t know what to do with, including the disabled and LGBTQ people. A Nicaraguan man was put in solitary for almost two months in the Florence Service Processing Center in Arizona. The only listed reason: “Detainee utilizes crutches — deformed leg.”

A 2017 audit of five ICE detention centers by the inspector general for the Department of Homeland Security identified “problems that undermine the protection of detainees’ rights, their humane treatment, and the provision of a safe and healthy environment.” Detainees were locked away for offenses as minor as sharing a cup of coffee.

How long can someone be held in isolation?

There is no legal limit on how long detention centers can keep a detainee in solitary confinement. International standards established by the U.N. special rapporteur on torture hold that isolation for more than 22 hours a day for more than 15 days in succession constitutes “inhuman and degrading treatment.”

Under standards set by ICE, a detainee’s stay in isolation must be reviewed at least every seven days, but NBC News found instances in which detention centers either failed to comply or failed to do the review properly.

Of the 8,400-plus incident reports reviewed by ICIJ, more than 5,100 described solitary confinement placements that exceeded 15 days. There were 573 placements that lasted 90 days or longer.

How is isolation harmful?

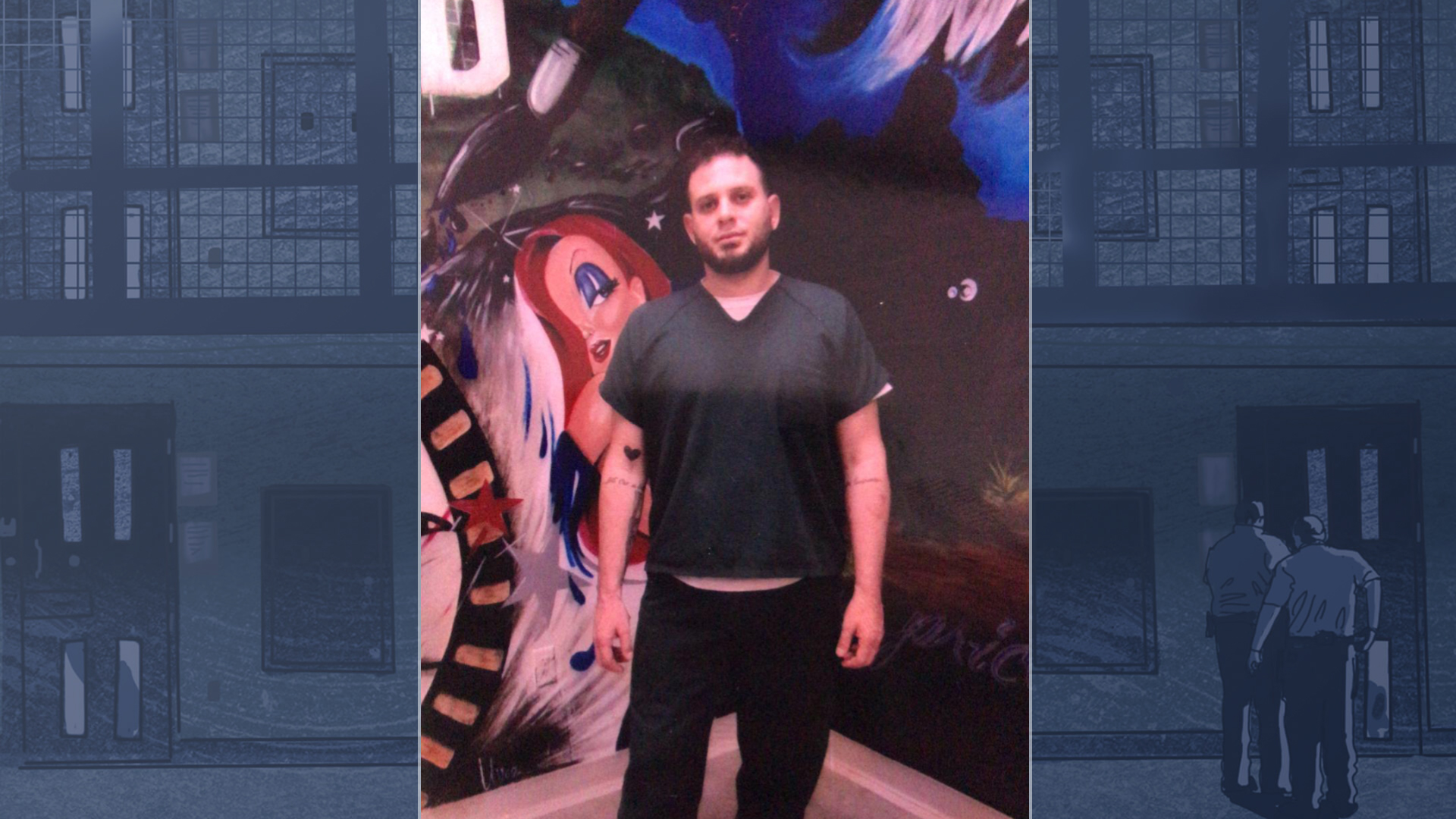

Experts who have studied solitary confinement — not to mention dozens of detainees who have experienced it — told ICIJ that the lack of social interaction can spark anxiety, panic attacks and suicidal impulses. Karandeep Singh, a 29-year-old man from northern India, said solitary confinement at an ICE detention center in El Paso, Texas, drove him into an emotional spiral ending in a suicide attempt in his tiny cell. “It’s only thinking, bad thinking,” Singh recalled. “It’s a different world.”

In 1999, a federal judge in Texas described isolation units in that state as “virtual incubators of psychoses — seeding illness in otherwise healthy inmates and exacerbating illness in those already suffering from mental infirmities.”

People who spend extended time in isolation are subject to a host of mental health problems, including paranoia, difficulty concentrating and memory lapses, according to Terry Allen Kupers, a professor at the Wright Institute who has studied solitary confinement extensively.

One study of the California prison system found that nearly half of the inmate suicides over a six-year period occurred in solitary confinement cells.

People with mental health problems, or those already in mental distress, are at greatest risk, but isolation can be traumatic for anyone. Detainees kept in solitary confinement for just five days told ICIJ that they continued to suffer flashbacks, had trouble sleeping and experienced depression long after they were released from solitary.

Who oversees ICE’s use of solitary confinement?

Homeland Security’s Civil Rights and Civil Liberties Immigration Section and the department’s inspector general oversee ICE detention, but it isn’t clear that either has been effective at policing ICE’s solitary confinement practices throughout the agency.

One serious challenge has been enforcing good recordkeeping. ICE’s directive on solitary states that it must keep detailed records of certain cases, such as when a detainee has been in solitary confinement for more than 14 days or was placed in isolation because of a mental health issue or another “special vulnerability.” The DHS inspector general has criticized the agency for failing to properly keep these records.

Global crisis support resources can be found via the International Association for Suicide Prevention.