This is the second installment of a four-part series from our Skin and Bone investigation.

In April 2003, Robert Ambrosino murdered his ex-fiancée – a 22-year-old aspiring actress – by shooting her in the face with a .45-caliber pistol.

Then Ambrosino turned the gun around and killed himself.

Soon after, Ambrosino’s corpse entered the United States’ vast tissue-donation system, his skin, bones and other body parts destined for use in the manufacture of cutting-edge medical products.

But before they entered the system, Michael Mastromarino, owner of a New Jersey-based tissue recovery firm, needed to solve a couple of problems.

He didn’t want to have to report that Ambrosino had perished in a murder-suicide. And he didn’t want anyone to know that Ambrosino’s family hadn’t given permission for his body to be used for tissue donation.

Mastromarino solved both problems the same way: He lied.

He claimed Ambrosino died in a car accident. And he claimed that Ambrosino’s family had agreed to donate his tissue before the rest of his remains were cremated.

Mastromarino was the leader of a now-infamous human tissue trafficking ring that fed an international trade in body parts. Along with tissues from Ambrosino’s corpse, he stole parts from grandmothers, electrical engineers, and factory workers, as well as from the remains of famed journalist Alistair Cooke.

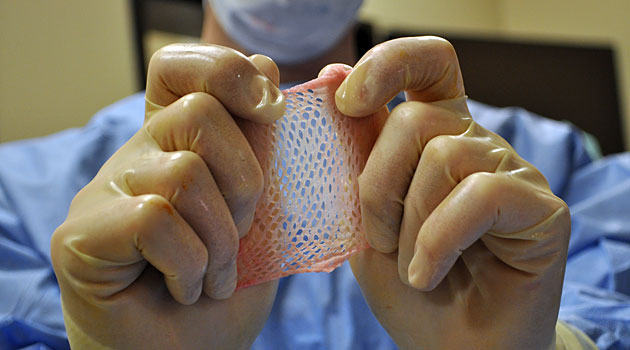

The disgraced dental surgeon from Brooklyn supplied the raw material for products used for a host of surgical operations – from knee repair to plastic surgery and cosmetic implants. He was a ground-level player in an industry that makes its profits by harvesting human tissues mostly from the United States, but also from Slovakia, Estonia, Mexico, and other countries around the world. One of Mastromarino’s top buyers was Florida-headquartered RTI Biologics, a processor of American, Canadian and Ukrainian body parts that trades among the high-tech companies on the NASDAQ stock exchange.

Years after Mastromarino was sent to prison and the publicity in his case quieted down, his story has been given new life by a lawsuit filed in a Staten Island courthouse. New York Supreme Court Judge Joseph J. Maltese has given the green light for RTI to stand trial Oct. 22 in a civil case that will delve into what the company knew – or should have known – about Mastromarino’s body snatching.

Evidence already filed in court raises questions about whether RTI was simply a victim of Mastromarino’s fraud, or whether it eschewed common sense in favor of its bottom line. An investigation by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) shows that the evidence in the case – and in other body-stealing scandals across the globe – also raises larger questions about the conduct of an industry that recycles more than 30,000 human bodies each year.

Police in places including Hungary and Ukraine, and North Carolina and Alabama in the U.S., have alleged that tissue suppliers stole tissue, committed fraud and forgery, or took kickbacks to pad their pockets. These cases suggest that Michael Mastromarino wasn’t the only body wrangler who has bent or broken the rules in the drive to supply the industry with flesh and bone.

A fantastic product

Mastromarino, now 49, is doing time at a maximum-security prison outside Buffalo, N.Y., serving a sentence of up to 58 years. He describes himself more as a human tissue broker than a body thief.

“This is an industry. It’s a commodity. Like flour on the commodity exchange. It’s no different,” Mastromarino said. “I cut some corners. But I knew where I could cut corners. We were providing a fantastic product.”

For more than three years until his crimes came to light in late 2005, Mastromarino’s firm supplied bones and other tissue to RTI’s nonprofit subsidiary, RTI Donor Services, and four other U.S. companies.

Mastromarino was familiar with RTI’s operation from his previous career as one of the busiest dental surgeons in Manhattan. He regularly used products derived from cadaver bone on his patients and, in that capacity, he had signed a consultancy agreement with the company in 2000 to help further refine RTI’s products.

But Mastromarino’s personal life was falling apart. He started injecting prescription painkillers to sooth an old football injury, became an addict and got busted for drug possession. He tried rehab three times before giving up his medical license.

Familiar with the industry and good with a scalpel, Mastromarino opened his own human tissue recovery company. He called it Biomedical Tissue Services.

The process was easy. Mastromarino filled out a form downloaded from the website of the Food and Drug Administration, the agency that regulates the industry in the U.S.

He didn’t have to wait for the FDA to inspect his facilities. He began supplying body parts right away – with more than a little help, he said, from an industry leader, RTI Donor Services.

“RTI set me up,” Mastromarino testified in a pending civil case. “They then said, ‘Listen, we can get into your business, we can get you started, we can open up your own business.’”

‘Santa’s naughty list’

The parties signed a supply contract in March 2002.

Not long after, Mastromarino’s colorful language and short fuse led to complaints from RTI staff. There were also rumors about his alleged involvement with organized crime, according to testimony of Caroline Hartill, RTI Donor Services’ vice president of quality assurance.

Court documents outline that RTI executives were concerned enough to hire a lawyer to run a background check on their new business partner.

“The good doctor has been on Santa’s naughty list for quite some time,” the lawyer, Jerome Hoffman, wrote in December 2002. “I would strongly encourage you not to do business with someone that has this kind of resume.”

A few weeks later Hoffman further urged RTI to give Mastromarino “the required 60 days notice under the current contract and not sign a new contract.”

RTI didn’t heed the lawyer’s advice.

Instead, on Feb. 11, 2003, Caroline Hartill signed an amended contract with Mastromarino’s firm.

In the new contract, his name was replaced with a freshly licensed doctor who lived in another state and with whom Hartill had never spoken. The doctor served as the medical director of Mastromarino’s firm – according to the signature on paper at least.

Hartill testified in the pending civil case that the amended agreement was simply a routine part of accreditation with the American Association of Tissue Banks, an industry body that oversees some of the biggest tissue banks in the U.S. She said her company wanted the medical director to take Mastromarino’s place on the contract because RTI determined it “would like to have more direct interaction with some of the other key principles [sic].”

RTI discounted the law firm’s concerns, she said, because if Mastromarino had “turned his life around, then who was I to pass judgment on him?”

Mastromarino recalls events differently. He testified Hartill and another RTI executive called him confidentially. They worried about competitors discovering his background and using it against the company, they said. And that’s why, Mastromarino said, his name came off the contract.

“Okay, whatever you guys want to do to make it comfortable,” Mastromarino told them, according to a deposition he gave in the current civil case.

The company refused interview requests from ICIJ and did not respond to detailed questions provided more than a month before publication.

Reasonable fees

RTI turns to corpse wranglers for a simple reason: It needs dead bodies to turn a profit.

“We cannot be sure that the supply of human tissue will continue to be available at current levels or will be sufficient to meet our needs,” RTI warned stockholders in securities filings. “We expect that our revenues would decline in proportion to any decline in tissue supply.”

And it isn’t alone.

More than 2,500 companies registered with the U.S. government rely to varying degrees on the fees they charge for crafting implants made from human tissue.

The world’s largest human-tissue bank, Musculoskeletal Transplant Foundation, took in nearly $400 million in revenues in 2010.

MTF is set up as a tax-exempt nonprofit, like most organizations that recover the tissue from donors located through hospitals, funeral homes and morgues. Most recovery outfits supply processing companies like RTI, which clean the pieces and mill them into usable implants. The processing companies in turn distribute them directly to hospitals or use an outside vendor such as medical device giant Zimmer to ship them around the world.

Players bid for exclusive access to U.S. donors. For example, medical device company Bacterin announced last year that it “successfully secured rights of first refusal of human tissue with multiple recovery agencies.”

Competition has spawned bitter court battles. MTF sued Bacterin last year for hiring former employees who, the lawsuit alleged, used their inside knowledge to pitch a rival bone product to MTF customers. “The very foundation of MTF’s business is under direct attack,” MTF argued in its complaint.

Publically traded NuVasive sued MTF and its partner Orthofix, accusing it of infringing on a patent for stem cell-laced bone implants. And nonprofit LifeNet Health sued Zimmer over reimbursement fees for processing bone plugs.

RTI gets tissue directly through its nonprofit subsidiary, RTI Donor Services, and has also obtained tissue from other nonprofit tissue banks in at least 23 states.

The Alabama Organ Center is one of RTI’s suppliers. It was embroiled in scandal this spring when its second-in-command, Richard Alan Hicks, pleaded guilty to accepting kickbacks from a funeral home in exchange for tissue recovery contracts.

“There are too many loopholes. There are too many temptations. There’s too much money out there,” Hicks’ attorney Richard Jaffe told ICIJ in June. “This industry is out of control.”

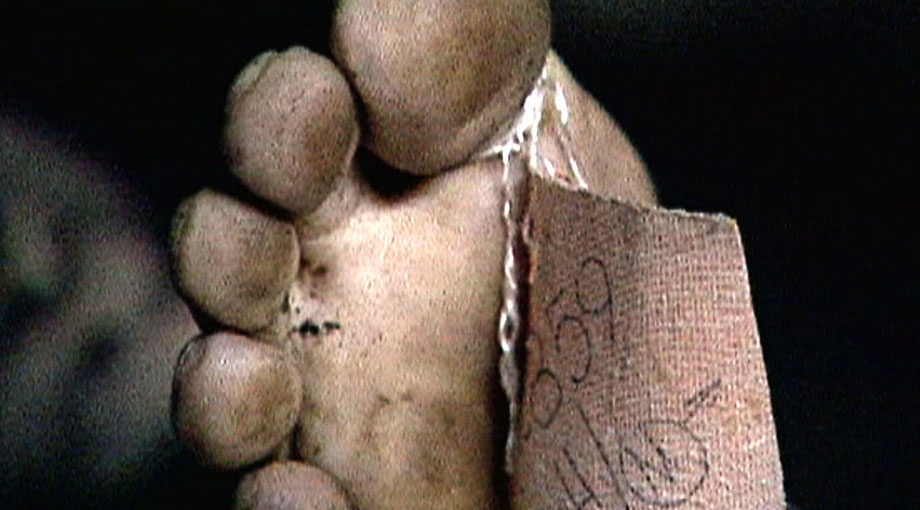

The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio has also recovered tissue for RTI. Its contract includes a fee chart – attaching different prices to the same tissue based on the donor’s age. RTI reimburses the recovery bank $1,755 for a 20-year-old femur; but $553 for the same bone from an 80-year-old.

In 1984 Congress passed the National Organ Transplant Act, making it illegal to buy and sell human organs and other human tissues. But it allowed charging “reasonable” fees for recovering, cleaning and distributing those parts.

Younger tissue is stronger and can be more lucrative for tissue processors because it can be used for higher-value grafts. Neither RTI nor the University of Texas responded to repeated requests for clarification about why the same tissues would carry such varying fees.

ICIJ turned to Christina Strong, a lawyer for organ procurement organizations (OPO) and tissue banks including tissue giant MTF. ICIJ asked whether there could be any reason other than the quality of the tissue itself for a bank to pay more for younger tissue.

“I have not found a satisfactory answer that makes me like this,” she said, pointing to the contract. “I do not like this. I would say to my OPO, ‘Don’t sign that.’ ”

Strictly confidential

With so much competition for American cadavers, some companies seek raw material overseas. That’s created a fertile market in Eastern Europe for body brokers and other middlemen who can help supply the tissue trade.

One of the middlemen was Igor Aleschenko, a Russian coroner working in Ukraine. In coordination with Ukraine’s ministry of health, he launched BioImplant, a state-owned tissue procurement center to supply Tutogen, a German medical products company.

Bioimplant supplied Tutogen with tissue. But Tutogen executives raised internal questions as early as 2001 about whether it should pull out of Ukraine, according to an internal memo marked “Strictly Confidential!!!!”

Aleschenko was asking for more and more money to play the role of intermediary between the regional satellite morgues around Ukraine and Tutogen in Germany.

“The flow of money is difficult to track,” the memo read. “Direct control over our resources is impossible.”

Staying in Ukraine would be high-risk, the authors determined.

“We can’t control the activities of the middlemen, and commitments are not being honored,” the memo said.

But the relationship did not stop.

Over time, 25 Ukrainian morgues registered with the FDA, each listing Tutogen’s German phone number on its registration forms. Since 2002, BioImplant and Tutogen have collectively exported to the United States 1,307 shipments of tissue – mostly bone, skin and fascia sent from Germany.

Families in Kiev first began complaining to police in 2005 that a morgue that was supplying Tutogen’s needs was taking tissue without proper consent. The criminal case was closed after an initial investigation. Prosecutors determined that, under Ukrainian law, they couldn’t prove a crime had been committed if they couldn’t prove that the tissue had been transplanted into someone, court records show.

Three years later Ukrainian police investigated another Tutogen supplier – this time in central Krivoy Rog. Those charges were dropped after the director of the morgue died while the jury deliberated in his criminal trial. Then in February of this year, police raided the Nikolaev morgue in southern Ukraine.

Some families claimed they were tricked, pressured or threatened into consenting. Police said in some cases signatures had been forged.

Aleschenko has reportedly slipped out of Ukraine for his native Russia. The Ministry will not respond to questions about his whereabouts.

Roman Hitchev, the founder of a major Bulgarian tissue bank and now president-elect of the European Association of Tissue Banks, said he was invited to Ukraine a few years ago at the request of the regional government in Odessa. Officials wanted to operate a bank similar to that of Tutogen suppliers in Kiev. Hitchev said he left, unconvinced.

“They didn’t have legal infrastructure, laws. Regulations were insufficient,” he said. “There was too much vagueness, too much uncertainty concerning who’s responsible in terms of control, traceability. I don’t like what I saw, and I just walked away.”

Clean inspections

The market for fresh bodies in former Soviet republics was alluring enough that even Michael Mastromarino – the New York dental surgeon turned body broker – tried to get in on the action.

He had connections in Kyrgyzstan. He flew there to meet with a top prison official. The official wined and dined him, Mastromarino said, and promised to sell him the bodies of executed inmates.

Mastromarino went home, energized at the prospects for new supply and revenue streams. He asked the FDA about importing tissue from the country.

The FDA was concerned about the risk that tissues harvested from Kyrgyzstan might carry Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, a fatal neurological disease akin to Mad Cow disease.

It gave Mastromarino an answer he didn’t want to hear: “No.”

So he had to be satisfied with his domestic sources of bodies. For a time, that was fine. Business was good, and he managed to avoid too much scrutiny from his buyers or regulators.

During audits of Mastromarino’s company by the FDA and RTI, no one tried to verify whether consents obtained from donors’ families were legitimate. Consents were often marked as having been taken by phone. U.S. law requires telephone consents be recorded, but no one double-checked to see if he was actually recording the telephone consents – or even getting them at all.

A Pennsylvania grand jury later condemned the entire inspection process. “If the lies in the records claimed compliance with regulations, that apparently was sufficient,” its 2007 findings read.

Even as Mastromarino’s company was passing inspections and booking profits, outsiders raised concerns about his business practices. Maryann Carroll, director of the New Jersey association of funeral directors, complained to RTI that Mastromarino was approaching funeral homes using RTI letterhead.

“Maryann feels like this reimbursement is excessive and looks like he’s buying donors,” an RTI employee wrote executives, according to undated correspondence detailed in court records. “She claims that if the press gets ahold of this story and slams the donation, then RTI will be dragged into this and her association will state that this is the second time that we were notified and did nothing.”

RTI’s nonprofit Donor Services unit signed a new contract with Mastromarino in June 2005.

RTI didn’t know at the time it signed the new contact, the company later said, that criminal investigators had begun looking into Mastromarino’s operations.

Pizza parlor

RTI wasn’t the only big company wanting to do business with Mastromarino.

In August 2005, LifeCell Corporation, a provider of skin grafts for burns, plastic surgery and bladder slings among other procedures, invited Mastromarino to its headquarters in New Jersey. It told him it could pay close to $10,000 per body if he could supply the skin from at least 400 donors a year, according to a copy of the presentation. That could have been worth millions of dollars a year to Mastromarino.

Two weeks after making its pitch, LifeCell received a letter from the Brooklyn District Attorney. Police in New York had been investigating Mastromarino’s body-stealing ring for months, after discovering forged consent forms at a Brooklyn funeral home. The DA asked LifeCell to forward any information it had relating to Mastromarino’s firm.

LifeCell did not respond to specific questions posed by ICIJ. In a statement the company said “It was LifeCell’s extensive donor review process that detected irregularities with Biomedical Tissue Services consent documents in September 2005.”

On Sept. 28 – three weeks after prosecutors asked for LifeCell’s records – Dr. Michael Bauer was clearing donor charts for LifeCell. He had always handled the donors provided by Mastromarino’s firm. But he had never tried to independently verify information. He was unaware, he later said, of the ongoing police investigation, but that night something made him do what he’d never done before. He tried calling the number for one of the physicians listed in a donor file.

He got a pizza parlor instead.

In the scandal that followed, LifeCell, RTI, Tutogen, Lost Mountain Tissue Bank and Central Texas Blood and Tissue recalled a total of 25,000 products – 2,000 of which had been sold overseas to Australia, South Korea, Turkey, Switzerland and other countries.

Live fast, die early

Mastromarino’s case brought a spate of bad publicity to the industry. The unwelcome attention flared up again in August 2006, when a similar case broke in North Carolina.

Philip Guyett had been working in the tissue industry for more than a decade, starting in California, then branching out to Nevada and, eventually, North Carolina.

Along the way, Guyett discovered that the best way to find young, healthy corpses was by trolling county morgues and funeral homes in lower-income locales with high crime rates, or by targeting cities like Las Vegas, where young people act stupid and die early.

Like Mastromarino, Guyett smoothed the process of selling off body parts with creative record keeping. He forged information on donor files, in one case selling hepatitis-infected tissue with a clean vial of blood from a different corpse.

“It’s ridiculous. I should never have been able to start a recovery business,” he told ICIJ in a recent interview in prison.

“I submitted the form online and in three days I was an official recovery tissue bank registered with the FDA,” he says is a book written about his career. “It’s harder to sell a hot dog on the street than it was to recover transplant tissue.”

Guyett pleaded guilty to three counts of fraud and is serving eight years in a federal prison.

The Mastromarino and Guyett cases prompted U.S. Senator Charles Schumer, a New York Democrat, to push legislation to help rein in the tissue-processing industry. The proposal would have required that new tissue banks meet minimum standards and undergo regular inspections by the FDA. It would also have required the federal government to define “reasonable” fees – a change companies tell shareholders could endanger future revenue.

His bill died because of hard lobbying by the industry, Schumer said. “They said it wasn’t needed. They said that ‘Everything is under control,’ but I had real doubts,” he recalled. “The bottom line here is, what we saw happen in the Brooklyn funeral home could well be happening in lots of other places both here and abroad, and there’s no real protection.”

Mastromarino agrees.

“Nothing is going to change,” he said. “There are too many people making too much money.”

Pointing the finger

After pleading guilty to avoid a possible 8,673-year prison sentence at trial, Mastromarino told prosecutors that his buyers – RTI, Tutogen and LifeCell – were not simple victims of his crimes. “Just look at how it works,” he told them.

Prosecutors said they didn’t find evidence to corroborate his claims. But families of the desecrated dead are now pressing civil charges accusing RTI of negligence – “not so much exactly what they knew, but what they should have known,” plaintiffs’ lawyers explained to the judge during the lawsuit’s pre-trial combat.

If the case does make it to trial, as scheduled, in October, Mastromarino’s story is expected to be a centerpiece of the plaintiffs’ evidence.

Important enough to the plaintiffs’ case, in fact, that lawyers for RTI Biologics fought to have his testimony thrown out. Mastromarino had already pleaded guilty to defrauding RTI and Tutogen, attorney Nancy Ledy-Gurren told Judge Maltese. He can’t turn around and point the finger at them now, she said.

Judge Maltese disagreed.

“You basically want to muzzle Mastromarino from saying anything that involves what your clients said to him – that dialogue that raises the specter of ‘What did they know and when did they know it?’” the judge told the company’s lawyers during hearings last fall.

In the judge’s view, just because the district attorney never prosecuted the executives from the bigger companies doesn’t necessarily mean they didn’t “participate in an enterprise.”

At the least, the judge said, the victims’ families have a right to argue: “They should have known. I mean, how could they be so naive?”

This story was co-reported by National Public Radio (USA).