This is the third installment of a four-part series.

The Kentucky man died in an off-road vehicle accident last year. His liver and kidneys helped save three dying patients in his home state. Musculoskeletal grafts taken from his heart, skin and bones were used in medical products used to improve the lives of 15 people around the country.

But soon after the transplants, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) learned the organ recipients had contracted hepatitis C. It turned out the Kentucky donor had a history of substance abuse and had served prison time. The tissue bank that recycled his remains, the CDC said, had screwed up the usual testing done to verify that tissues and organs were safe.

The CDC’s Office of Blood, Organ, and Other Tissue Safety deployed a team of “shoe-leather epidemiologists” to track down the tissue before someone else got sick. Unlike hearts and other organs — or blood products that come with a unique barcode — there’s no easy way to track down tissue.

Instead the team found tissues one-by-one, calling hospitals and chasing down doctors. It took nearly a month to locate all the surgeons who had implanted tissue into 15 people. A child, later found to have hepatitis C, had received an infected heart vessel patch before the tissue recall began.

In some cases, inconsistent or non-existent recordkeeping prevents medical sleuths from ever finding potentially infected tissues. In one major case that played out in 2006, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and five tissue companies moved to recall 25,000 tissues taken illegally from U.S. donors without proper consent or testing. Eight hundred of the tissues shipped overseas were never found.

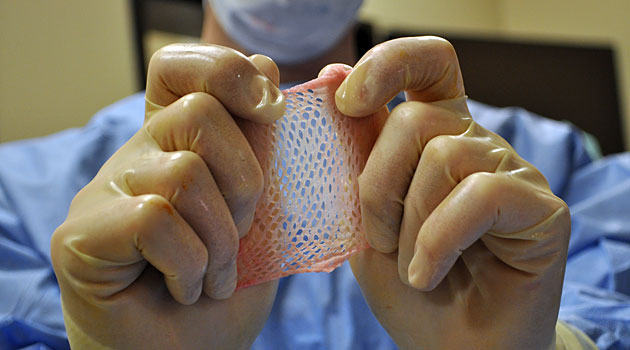

The trade in human tissues is virtually untraceable at a global level. Poor accountability and inadequate safeguards have prompted concerns among medical experts that products made from bone, skin, tendon and other tissues taken from the dead could spread disease to the living — putting patients who receive tissue implants in dental surgery, breast reconstruction and other procedures at risk.

Little has been done to address this problem, despite U.S. government reports that have raised red flags for the past 15 years — and despite continuing concerns by the CDC and the World Health Organization.

Lack of transparency

The United States is home to the human tissue industry’s largest players and provides as much as two-thirds of the world supply. But the U.S. government neither knows where imported tissue originally comes from nor where exported tissue ultimately goes.

Transplants of hearts, lungs, kidneys and other intact organs are tightly monitored because organs have to be a near-exact physical match and move immediately from donor to recipient. Hearts and other organs are charted with unique identification numbers that trace back to their donors.

By contrast, cartilage, bone and skin can be stored for months or years and shipped from place to place. Tissues aren’t given standard identification numbers that allow health authorities to track them.

Some health experts have proposed — without success — that the U.S. and other countries adopt a barcoding system that would allow them to track tissues across state and national borders. It wouldn’t be difficult, and it wouldn’t be too costly either, they say.

“If you think of Wal-Mart, they pass through millions of products that are scanned,” said Reena Mahajan, a CDC investigator who worked on the case of the hepatitis-infected Kentucky donor. “If they had a recall, it would be very easy.”

Without the ability to systematically track products made from human tissues, officials can’t respond efficiently if infected tissue is recalled. Nor can authorities assure tissue has been taken legally — or from countries with low risk for deadly infections such as Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, the undetectable human equivalent to mad cow disease.

A pilot program implemented in the United States to follow the traffic of tissue products showed promise. But without industry support or a federal mandate, the program died. On a global scale, the World Health Organization has tried for years to collect data on the global trade. The effort collapsed when most countries — including the United States — failed to provide any data. Now the WHO has refocused efforts on trying to convince counties why they should care.

Mar Carmona, part of a two-person team trying to investigate the issue for the WHO, says the lack of participation from the U.S. helped cripple the program. “If you don’t have the U.S., and they’re the biggest country,” she said, getting a sense of the global picture is almost impossible.

Carmona’s boss at the WHO is Dr. Luc Noël.

“I am not sure anyone has complete and precise tissue banking activity data for the USA. I only have estimations,” Noël said. And without traceability — without transparency — the trade is vulnerable to unchecked infection and illicit networks in a way organs are not. “You store, you ship, you can blur the tracks,” he said. “It fits into the legal and illegal trade without much difficulty.”

FDA: “It doesn’t ring a bell”

The United States allows companies to import tissue provided the donors are not from countries, such as the United Kingdom, with a history of mad cow disease. It sets no limits based on a country’s quality of transparency or human rights record. So England is out, but Ukraine is in.

In Ukraine, police have uncovered what they believe to be cases of illegal tissue recoveries that bring into question the safety and oversight of material that is regularly imported into the United States.

U.S. regulations do nothing, however, to address the potential for improperly obtained body parts, said an official with the FDA, the agency tapped to police the trade. They only focus on “safety and efficacy. They do not have anything to do with what’s going on in the other countries. Our regulations and our guidance would not address something like that.”

Nor does the FDA know where all human tissue is coming from. Not all imports are clearly marked as human — or even as tissue. Instead, shipments come in under vague import codes such as “Orthopedic Implant Material.” Imports are logged into the system with a “country of origin.” But that doesn’t always lead to the source country. For example, Ukrainian tissue has been sent to facilities in Germany for processing or storage and exported to the U.S. as a product of Germany.

The FDA last year required Florida-based RTI Biologics to change its practice of identifying tissue originating in the Ukraine as German. The company bought out Germany-based Tutogen in 2008 after a long trade partnership. BioImplant — RTI’s Ukrainian supplier — has since begun exporting significant amounts of tissue to Florida directly from Ukraine.

Without being able to identify the true country of origin, officials might not connect cases of illicit tissue harvesting with products distributed in the United States — if they were even aware of such cases.

FDA officials said they were unaware of investigations carried out in Ukraine. Dozens of families complained their loved ones’ tissues were taken illegally in morgues that are also FDA-registered tissue banks and shipped to Tutogen, a subsidiary of RTI since early 2008.

The first case, from 2005, was dropped when investigators ruled that the law made it difficult to prove whether a crime had been committed. The second case, from 2008, was closed when the supplier on trial died just before a jury returned its verdict. The third and fourth cases, from earlier this year, are still pending.

“If we had any intelligence about a concern, we would flag them accordingly and take the appropriate action,” a high-ranking FDA import official said. “If something came in we’d probably hear about it. But it doesn’t ring a bell with me.”

FDA officials spoke on background, but in the presence of agency press officers. They refused previous and subsequent requests to speak on record.

Broken chain

Companies in the U.S. distribute more than 2 million tissue products a year. These distributors should be able to track tissue from donor to hospital buyer if something goes wrong. After that, it’s the hospital’s responsibility — although not by law — to assure traceability continues to the recipients.

The doctor who implants the tissue can choose to fill out a postcard and send it to the tissue manufacturer, noted Scott Brubaker, chief policy officer of the industry group the American Association of Tissue Banks. “But this practice is voluntary and compliance is sketchy,” he wrote in a book to be published this summer.

Brubaker pointed to increasing difficulties that face companies trading tissue cross-borders. “Tracking capabilities need to be ensured particularly where there is the possibility of importation into one country and then redistribution to others,” he wrote in a report prepared as part of a 2011 conference about the global tissue trade. “For the exporter, traceability ends with the first stop in the chain of custody; the final disposition of grafts can remain unknown.”

Surgeons are not required to inform tissue companies when they use a graft or when a patient gets sick following a transplant. And even if they do hear about an infection, the companies are required to report only the most serious to the FDA. Experts suspect infection rates are low, but no one really knows.

“There is no good traceability system right now, no barcoding, we don’t have surveillance, just shoe-leather epidemiology,” said Dr. Matthew Kuehnert, director of the CDC’s blood and biologics unit. “Without surveillance, you can’t say anything.”

Between 1994 and 2007, authorities issued recalls for more than 60,000 tissue grafts. But because doctors aren’t required to tell patients that the medical device is human, patients might not connect a subsequent infection with the graft itself.

“If the clinician hasn’t explained the patient got human tissue, how do you explain there was a recall?” asked Kuehnert. “Physicians say they don’t want to test the patients. We ask, ‘Why not?’ They say, ‘I don’t think they realized they got an allograft. So how do I explain why they need HIV or hepatitis testing done?’ ”

Tissue can be infected with cancer, bacteria, fungus, tuberculosis, HIV, even rabies. Scariest of them all perhaps is Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, which can incubate undetected in a body for decades. CJD attacks the nervous system and is always deadly.

Dozens died in the 1980s and 1990s from CJD-tainted tissue. In response, the FDA forbids companies from selling medical products in the U.S. made from tissues imported from the European Union and other regions where mad cow disease had emerged. U.S. companies can still obtain tissue from countries deemed low risk, such as Slovakia. Then they can distribute it in places outside the United States.

CJD is a known unknown. Of even greater concern are diseases that have yet to be discovered.

“I worked in the AIDS era. It was a new virus; no one knew much about it,” said Dr. Duke Kasprisin, who has worked in the blood and tissue industry for decades. “We always have a certain squeamishness that something like that can occur again, that there’s some new virus on the horizon that we’re not thinking about today and wouldn’t recognize it.”

“You’re only as good as the current set of infections,” Kasprisin added. “We’re … trying to make sure we’re not dealing with something different, something new, something transmissible.”

Economist Angelo Ghirardini with the Italian Transplantation Center developed a national system to trace organs more than a decade ago. He followed that in 2008 with a way to track other human tissues such as bone, skin and veins. From his office in Rome, he proudly displays the real-time software that follows activity of Italy’s 34 tissue banks.

Using a unique identification code, Ghirardini can tell you where a piece of tissue is at any given time — all the way from donor to recipient. His team is part of a consortium working to create a common coding system for the European Union’s 27 countries.

“It’s a priority,” said biologist Deirdre Fehily, a member of the Italian team. “It’s seen as a primary way of improving safety … and also addressing ethical issues. Because if you can trace to the origin, you can investigate consent issues.”

The system is required by law. But with so many languages and governments to accommodate, it’s running behind schedule. The team anticipates the program will be live by 2014.

Europe and the U.S. took different approaches to regulating products made with human parts. Most European countries limit the number of banks per region based on a population’s need. The United States does much the same thing with life-saving organs. But regulations are less restrictive with the other human remains.

“The U.S. early on in the history allowed profit making,” Fehily explained. “Can you imagine in the States someone saying, ‘Connecticut can only have three bone banks’? If someone wants to start a bone bank, they start it.”

Grim outlook

The Government Accountability Office (then called the General Accounting Office) first reported on the lack of traceability in the budding U.S. tissue industry in 1997. “The current tissue-tracking system is inadequate to notify recipients who receive tissues later deemed to have been unsuitable for transplantation,” it found. Nor were companies required to report errors “or to report adverse events associated with the transplantation of human tissue.”

Following a series of stories published in 2000 by California’s Orange County Register about problems and profits in the tissue industry, the Office of Inspector General for Heath and Human Services found nothing had changed. “There is no national system for tracking the availability of tissue,” the 2001 report read.

That year U.S. lawmakers convened a hearing. They wanted to know why the government couldn’t properly regulate the rapidly-changing industry.

“We do not even know where the tissue goes right now. There is not even a way to sort out and track what happens to the tissue,” George Grob, then-deputy inspector general for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, told lawmakers. “And with the modern tissue banking industry, there are so many new processes coming into play all the time that it is difficult to even define the stages through which the tissue is going.”

In 2005, the FDA implemented rules requiring tissue banks to track their tissues from donor to distributor. But banks and hospitals maintained different tracking systems. And the government verified compliance through sporadic on-site inspections. Only about 40 percent of banks in operation today have any associated federal inspection record, according to an ICIJ analysis of the FDA’s inspection data.

Companies were also required to report at least the worst adverse events — but the company was given broad discretion to draw the final determination. For example, between September 2010 and October 2011, RTI received 758 complaints or reports of adverse reaction to their tissue, FDA inspectors noted in the company’s 2011 inspection. During that time RTI reported four adverse events to the FDA. The company declined requests for comment.

The AATB refused repeated requests over four months for on-record interviews. But during a background interview representatives said most often an infection following transplant cannot be directly linked to the tissue graft used. “A tiny, tiny, tiny minority when there is an infection ascribed to a specific graft,” an AATB offical said. “Tissue is safe. It’s incredibly safe.”

In 2007, the FDA, CDC and United Network for Organ Sharing implemented a pilot traceability system with a clunky name — the Transplant Transmission Sentinel Network. Companies volunteered to take part in the three-year barcode-based program.

The model was a success insofar as products could be tracked efficiently. But the effort also highlighted gaps in the reporting requirements, a lack of understanding the risks of disease transmission, and a lack of coordination among stakeholders.

“Concerns were also voiced about possible liability, impacting the willingness of participants to report adverse events,” researchers later noted. “The prototype proved that a system can be built, but to be quickly implemented nationally will require impetus from legislation or regulation.”

The program wasn’t renewed at the end of its three-year lifespan. The CDC’s Kuehnert is optimistic, but the outlook isn’t good.

“All I can say is that we recommend it. But there has to be the momentum to make it happen,” the CDC’s Kuehnert told ICIJ. “I think we take it for granted that cereal you buy at the store has a barcode on it and it can be tracked back if there is some sort of a problem. You can’t do that with tissue right now.”