MEET THE INVESTIGATORS

How to report on human trafficking: Inside Trafficking Inc.

In this month’s Meet the Investigators, journalists from our Trafficking Inc. project share what it was like to report on modern day slavery across the globe.

The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists collaborates with hundreds of members across the world. Each of these journalists is among the best in his or her country and many have won national and global awards. Our monthly series, Meet the Investigators, highlights the work of these tireless journalists.

For nearly a year, ICIJ’s Trafficking Inc. has uncovered webs of human trafficking across the globe, investigating underground networks that trap vulnerable people in coerced labor. The project has exposed hallmarks of labor trafficking on U.S. military bases in the Persian Gulf, suspected sex trafficking rings in Dubai and predatory loan operations that allegedly ensnare Filipina women seeking domestic work overseas.

This month’s episode brings together a panel of three journalists working on the project to share the unique challenges of their reporting, and what it takes to coordinate dozens of journalists and over three hundred interviews with workers across Africa, Asia and the Middle East.

TRANSCRIPT

Carmen: Hello and welcome back to Meet the Investigators from the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. I’m your host, Carmen Molina Acosta, and I’m a producer here at ICIJ.

If you’re joining us for the first time today, Meet the Investigators is a podcast where we hear from ICIJ journalists from across the globe.

Today, I’m sitting down with three of those who’ve been working on our latest investigation, Trafficking Inc. The projects uncovers human trafficking systems at work around the world, and how vulnerable people are being funneled into forced labor across Africa, Asia and the Middle East.

I’m going to let them introduce themselves:

Michael Hudson: Hi, I’m Michael Hudson, I’m a senior editor at ICIJ.

Hoda Osman: Hi. My name is Hoda Osman. And I work as executive editor for Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism, ARIJ.

Katie McQue: Hi, I’m Katie McQue and I’m a freelance reporter. I’m working with the ICIJ on the Trafficking Inc project, and I’ve been working on this project now for 18 months.

Carmen: Welcome everyone, thank you so much for being with us here today! We’re going to start with you, Michael, since you’ve sort of spearheaded this project from the very beginning. Tell us — where did it come from? What’s this project about?

You don’t need metal restraints to traffic a human being; you can manipulate employment contracts, immigration laws and labor laws to control and exploit them.

– Michael Hudson, senior editor at ICIJ

Michael: The beginning of it happened during our Pandora Papers investigation, which was a project that drew on a huge cache of records of offshore companies and who owns them, and we were reporting on the UAE as a center for dirty money, as a center for money laundering. And as part of that reporting, we looked at the money flows that come from human trafficking.

Carmen: When we say human trafficking, Michael, what are we talking about exactly?

Michael: There’s a lot of confusion and misinformation about this issue. I think it’s important to remember that when experts and activists say human trafficking or modern-day slavery, they’re usually not talking about people in shackles or locked in cages. Human trafficking frequently involves people being exploited by recruiters who use their poverty, isolation and immigration status against them. So you don’t need metal restraints to traffic a human being; you can manipulate employment contracts, immigration laws and labor laws to control and exploit them. In some countries in the Middle East, for instance, workers can be charged with the crime of absconding if they break an employment contract. And in many cases, local authorities don’t care if they left their job because they were being physically assaulted, or they were not being paid or being paid far less than what they promised.

Carmen: Right, so there’s a handful of stories that have come out as a result of this collaboration. You all have worked with all sorts of partners — ARIJ, like you mentioned, which is why we have the incredible Hoda Osman here with us today, but also places like the Washington Post, NBC, and most recently, Reuters. One of our latest stories delves into the thriving sex trafficking industry in the UAE. Michael, what can you tell us about this story?

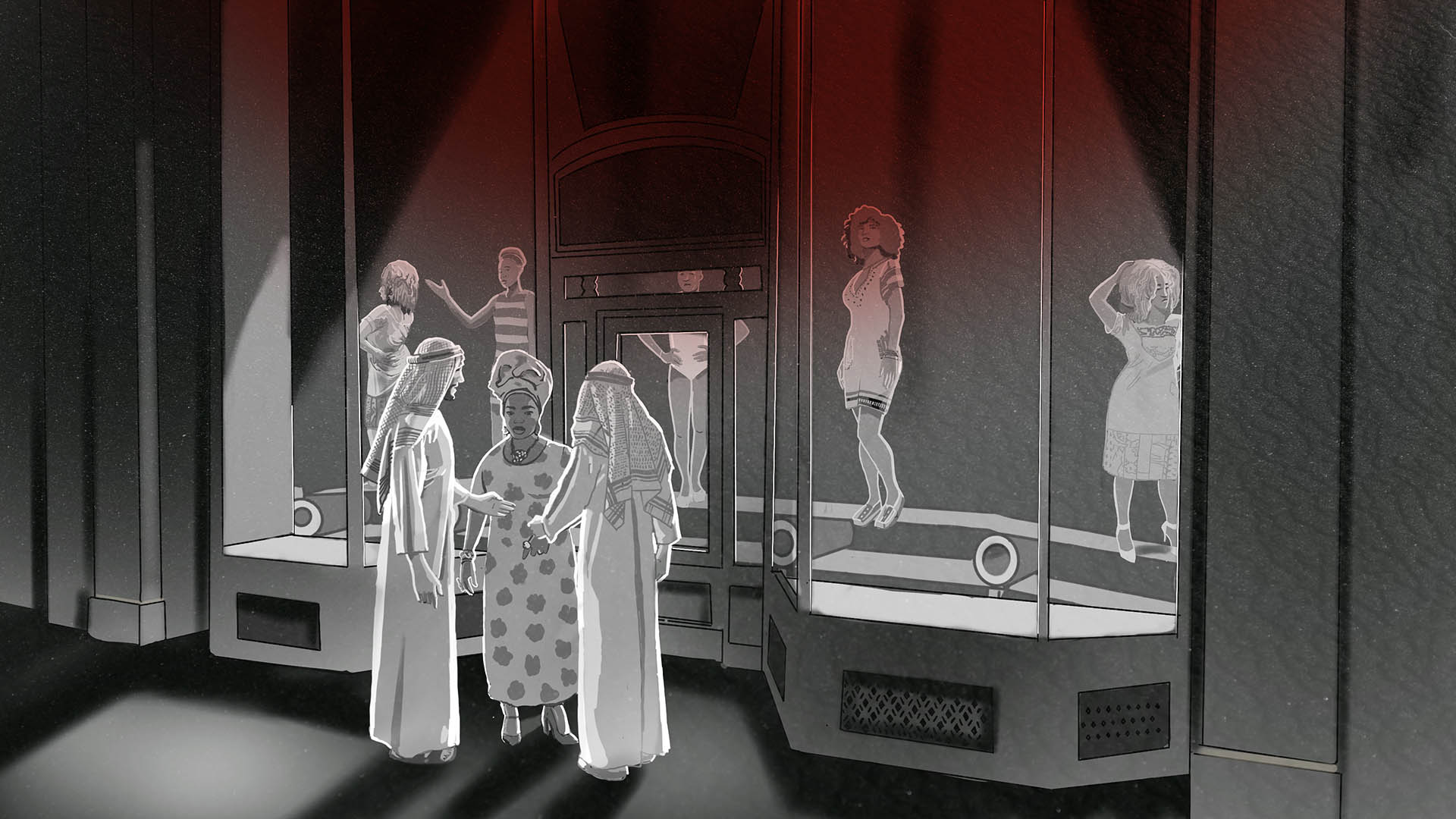

Michael: Yeah, this is a story that was reported by Maggie Michael, who was an ICIJ investigative reporter based in Cairo up until just recently. Now, she’s at Reuters and so, we’re co-publishing it. It’s about how human traffickers keep women from Nigeria and other African nations in sexual slavery by playing on their financial desperation and creating webs of manipulation and coercion. It’s mainly about a pipeline of sex trafficking between Nigeria and the United Arab Emirates.

Carmen: You can read that story on ICIJ.org and at Reuters.

This has been a long running investigation, it’s gone on for well over a year. I’m going to take us back to 2022, when you all collaborated with a number of partners on a piece about labor trafficking on U.S. bases in the Gulf.

[CLIP from NBC: “Now to our NBC news investigation, disturbing allegations that foreign workers at some US military bases overseas are the victims of human trafficking. Our report, produced in collaboration with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, The Washington Post and Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism.”]

Carmen: Hoda, as part of ARIJ, you were a big part of that story. Could you tell us a little bit about that reporting process and what that partnership was like?

Hoda: Sure, so as you know, there were several stories that came out of this project and the main story that we were working on was a collaboration with NBC News and The Washington Post about migrant workers who are hired to work on U.S. Army bases that are in the Gulf countries, and where the contracting companies would commit a lot of these violations, labor trafficking violations. And, in spite of internal investigations by the U.S. government showing that this was happening, these companies were still being given lots of money, in spite of the abuses that were going on. So our task, of course, our name — Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism — we focus on investigations in Arab countries. This is where our experience is and where our contacts are, so we were tasked with the on-the-ground reporting. So, finding the workers, meeting them face to face, going to the areas where they live, just, you know, field work.

Carmen: Reporters on the project interviewed dozens of workers who were brought in to these US bases from Africa and Asia to provide food services, mechanical support and unskilled labor. Several said they went into debt for the recruiting fees, and were paid far less than what was promised. Many reported their documents were withheld, and they were unable to leave even if they wanted to — all hallmarks of labor trafficking.

They were telling us that they desperately wanted to leave, find better jobs, but they absolutely couldn’t and they were — a lot of them were very scared.

-Katie McQue, freelance reporter for ICIJ

Hoda: We worked closely with an organization called Migrant Forum in Asia. They found one, a Nepali man, who had complained, and through them — he was in Nepal already living in a village — and through them, we organized the Zoom interview

Carmen: What was it like to talk to people who had been through this sort of thing?

Hoda: I have a particular moment related to that Zoom that we did with the Nepali man. I was, I was really impressed and touched that he agreed to do the interview over Zoom — he had to borrow the cell phone of his neighbor to be able to do it. And it was after he had finished a long day of work. It seemed like it was just like one room where it wasn’t very well lit or there was no electricity.

And he was speaking in Nepali and we had someone do the translation, but even when he was speaking in the language that I didn’t understand, I could feel his pain. One of the things that he said was that when he would go to the bathroom, he would be followed, basically, so he doesn’t waste a lot of time and get back to work and just keep on, continue to work. And at some point he took the phone, he kind of wanted to show us his two kids who were in the room. And I just always remember this interview and I’m very appreciative that he had agreed to do it.

Katie: Can I just add, because I was the other reporter on the project — I was focusing on Kuwait and Qatar. For four months, I interviewed almost forty workers and I was just speaking to them daily or quite frequently and just about their day-to-day lives but also about their concerns. They were telling us that they desperately wanted to leave, find better jobs, but they absolutely couldn’t and they were — a lot of them were very scared.

Carmen: Something all three of you have really touched on in this conversation so far is how vulnerable these people are, how complicated their situations are. How do you guys find them? How do you reach out, and how do you get them to trust you and to open up to you as a journalist?

Katie: In this project so far we’ve interviewed more than 300 human trafficking victims and most of them we’ve got in contact with them ourselves — myself and other reporters — through on the ground reporting, but also reaching out to people online, etcetera, as well.

I used to live in the Gulf, I used to live in the UAE and I’ve been doing this reporting for seven years or so. So I’ve built up a source network of migrant workers on the ground that I speak with and I kind of also reach out to new people all the time. Generally online, in different spaces. I can see what people are talking about and sometimes, just in Facebook groups, and you can kind of identify who is a human trafficking victim. And then I just kind of reach out to them and explain exactly who I am, that I’m a journalist and I’d like to talk to them about their situation and then just take it from there.

But what is really something that is very, very important is just making sure that they know exactly who you are. Because so many of these people are vulnerable and they’re just looking for help, that you need to make sure that they’re not — that they don’t have any false hopes you can help rescue them, or help or alleviate their situations in any way. So I just try and get to know them, have conversations with them, sometimes like I said, over months, without disturbing them too much. Because I don’t want to raise their hopes. And so that takes a lot of explaining, and usually people understand, but sometimes they don’t. And I’ll just kind of have to kill the conversations because, again, somebody that’s had that happen to them already, you just don’t want to be manipulating them inadvertently or messing with them in any way.

Carmen: As reporters, you’ve been really immersed in this world and in this topic for a while — what are some of the things that stick with you?

Katie: I think speaking with these trafficking victims throughout this project, the thing that strikes me is just the vastness of the amount of people that fall prey to human trafficking through no fault of their own. The amount of times I’ve had human trafficking victims say “We’re treated like animals. We’re not, we’re not human,” is very common and it’s true. This process absolutely dehumanizes these people and they, in terms of labor trafficking, are just seen as tools to get a job done.

Conversely, the other point that I’m taking away from this project is about human traffickers: they are human. They’re not monsters hiding in the shadows. A lot of these people have been trafficked by their uncles, family friends that have been caught up in recruitment schemes. Often what we would regard as human traffickers are heroes in their local communities because they’re sending people away to foreign countries to earn money. If it goes right, they are seen as pillars of their communities. So I think hopefully readers will understand that human traffickers aren’t some boogeyman far away. They walk among us as well. And they have families themselves and they’re also human. And they’re also part of this process. And I think that those are the two aspects I’m taking away from this project, with relation to the humanity of these people.

Michael: I mean, one thing that sticks with me from, you know, editing, talking about and reading the work of Katie and other reporters who worked on the projects, ARIJ, people at NBC News and Maggie Michael, is just the ingenuity basically of companies and individuals who are traffickers, who are trafficking people, who are exploiting people. The different ways, very complex ways, that they are able to manipulate laws. And really, you know, manipulate the hopes and dreams of people who are just trying to get to another place so they can get a better job, and have a better life and help their family.

Carmen: Over the next few days and weeks, a few more project-related stories are coming out. One is about domestic workers from the Philippines falling victim to predatory loans and recruitment scams as they try to seek work abroad. And there’s another one also coming down the pipe. Can you give us a sneak peak?

Katie: We’ve seen through our reporting that there are some powerful players politically involved in the trafficking systems and networks that we’ve been investigating.

Michael: Right, politically and economically. So stories down the road, people may, in some countries and maybe in many countries, may recognize the names of the people and the entities that we’re going to be reporting on. I think that’s all we kind of want to say about what’s coming up.

Carmen: Alrighty. That’s an excellent cliffhanger, we’ll leave it at that. Thank you guys so much.

That’s it for this month’s Meet the Investigators — again, that was Michael Hudson, Hoda Osman and Katie McQue. The Trafficking Inc. stories we mentioned here today are live on ICIJ.org. Keep an eye out for the next ones. I’m Carmen Molina Acosta. Thanks for tuning in. We’ll see you next month.