ICIJ has hundreds of members across the world. Typically, these journalists are the best in the country and have won many national and global awards. Our monthly series, Meet the Investigators, highlights the work of these tireless journalists.

This month, we speak with one of the journalists who worked on West Africa Leaks, Maxime Domegni. He is one of ICIJ’s newest members. He is the editor of l’Alternative du Togo, the best-known investigative newspaper in Togo, but currently works from a neighboring country. Follow him on Twitter.

Tell us a little about yourself

I am the president of the Consortium of Investigative Journalists in Togo (Cojito), which we created in 2017. I’m also the former secretary general of the Union of Independent Togolese Journalists.

I studied journalism at the University of Lomé and started journalism in 2006. While I was studying, I was the editor of a university newspaper. It closed after I left. After that, I worked in the best-known newspaper in the country at the time Forum de la Semaine. I worked there until 2010, mainly on feature stories.

Then some of us felt the paper’s editorial direction was becoming a little too close to close to the government. So, in 2010 I left with a few friends and we joined l’Alternative.

It’s certainly not much fun to suddenly have to leave… In spite of that, it’s necessary to keep working and continue investigating. – Maxime Domegni

From 2010, we told ourselves, “We’re free now, we’ll start publishing l’Alternative regularly.”

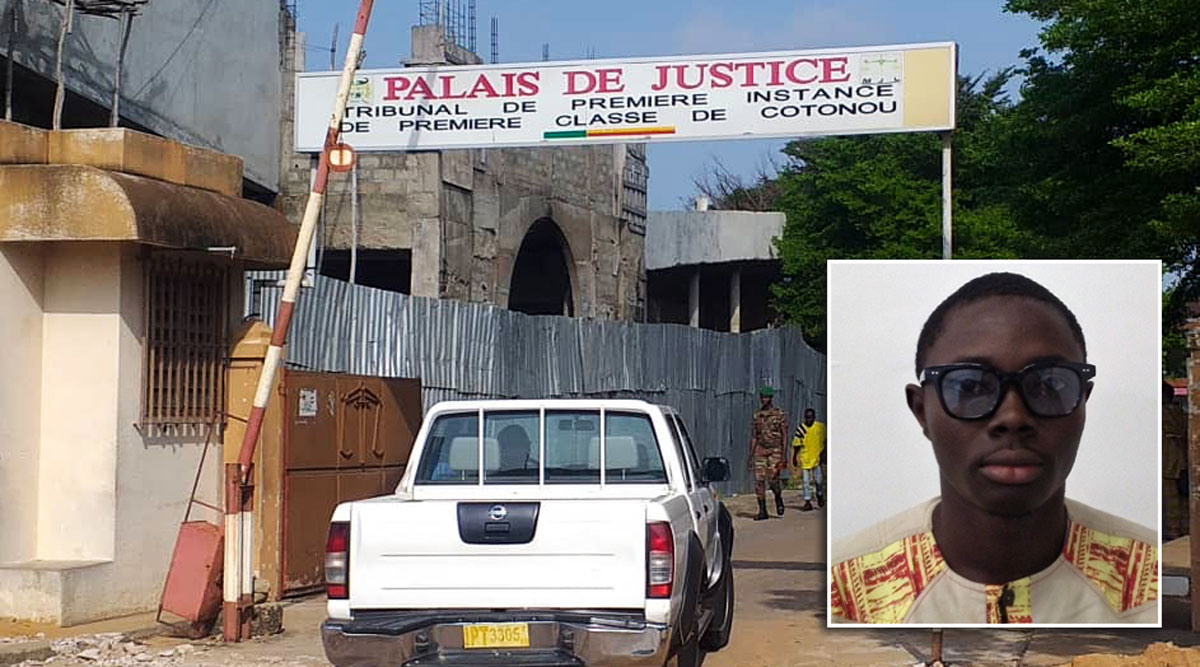

You left Togo last year. Why?

I left the country for a few reasons, including because of my work as a journalist.

The political situation had become unstable, and I was a potential target. I’d heard a few things through the grapevine about becoming a target.

I was part of a network created by journalists, artists and activists who saw the space for freedom of expression was shrinking. Anyone who resisted was suffocated. We were all experiencing that, so we told ourselves, “We can’t just wait through this until it kills us. We have to do something and gather our forces.”

For example, an anonymous person contacted me and tried to get me to work on a story about female trafficking. It was supposedly about a European who was in trouble in prostitution in Togo and Ghana. The person told me I couldn’t speak to anyone about it, but they were emailing and calling me openly. And they hadn’t even gone to the police. I think that whoever called probably wanted me to go to a particular place so they could pick me up. And then who knows what would have happened?

How do you work from outside the country?

It’s certainly not much fun to suddenly have to leave my family, colleagues and friends for security reasons and then move around other countries as a foreigner with all the restrictions that goes along with that.

In spite of that, it’s necessary to keep working and to continue investigating.

It is a situation that any journalist and advocate of democracy and good governance can never rule out. But when it happens, it’s an unpleasant surprise.

Of course, my work with the newspaper in Togo has been seriously affected by my current situation. I hope everything will go back to normal soon. Until then, you’ve got to stay professional and be as productive as possible.

What are you best known for in Togo?

Probably the Panama Papers investigation.

In that story, we first saw some Indian names [of shareholders of a prominent mining company in Togo]. The company in question was accused of violating workers’ rights in Togo for a long-time. It was very powerful. There was even a big explosion that had killed some people. [Editor’s note: Maxime’s story revealed that powerful Togolese politicians held shares in the company]

We all wanted to know who was behind this company. That’s when I decided to look for the shareholders. That information wasn’t online or in the Panama Papers. A source gave it to me, and that’s when I realized that a former prime minister other ministers were shareholders of the Togo company.

Previously, I often worked on mining company stories about phosphate and iron. I chose this sector because, although Togo is a small country with only 7 million people, it has a lot of natural resources.

And like we say for many African countries, instead of creating wealth, this wealth is instead wasted, and local people do not benefit from it. For example, the phosphate company I wrote about, Wacem, fired 700 workers and at the same time I was working on the Panama Papers investigation. And landowners were complaining, too.

Tell us a little about how you work

What I do often is search on online company registers to verify information.

As I’m interested in data, it allows me to do some more advanced online research, to trace information. I think that’s probably something I do that might be a little different from what other Togolese journalists do.

A source I consult very often is the website of Togo’s business registry, the Centre de Formalites des Entreprises du Togo (CFE).

This is a site that has information on companies – when the company was created, the person who signed for it, the people who are linked to it, the director. This is basic information but can sometimes reveal many things. For example, you can find that the real owner of the company isn’t the person whose name is on the documents. They might just have put their daughter on the document, for example.

Or you might see that the date the company was created shows it was created for a particular reason or a specific event.

I also have access to a list of Togolese company taxpayers. [In it] you see the name, the company’s tax number, the company boss. And from that you can to find out what other companies he or she is also involved in. I use it a lot to cross-check with the CFE.

That’s useful because often companies you know about are not listed under that name in the business registry. But if you have the owner’s name, you have a better chance of finding something.

You can spend hours looking for the name of a company as it appears on the street and it won’t be in the company registry.

When doing cross-border investigations, we try to speak to journalists around the world. The use of the internet these days means that some information can be hidden inside Togo but can be available in another country. For example, the amount of material that a company exports from Togo might not be available inside my country, but information on how much material is imported into another country from Togo might be available.

The fact that more and more data is available is a gift for investigative journalists.

What do you think are necessary characteristics of an investigative journalist?

Doubt, doubt, doubt.

You must be curious to get to the bottom of things every time. Fundamentally, you must be willing to question everything.

You need to remember that whatever anyone tells you, they tell it to you from their perspective, with their own interests.

For example, I focus more on people in public life whose affairs and business dealings have public interest. I focus on people who exploit public contracts or public goods, for example.

Daily journalism is about reproducing news as it happens. The need to verify facts isn’t the same as it is for investigative journalism. But with investigative journalism, you can be led to make mistakes. Someone can decide to deliberately mislead you or even mislead you unwittingly by thinking that they are saying something true.

So investigative journalists must verify everything and have documentation.

What is the one thing you could change to improve the lives of investigative journalists in Togo?

Access to information.

The law says public officials have the duty to be transparent. Even our press code says anyone who prevents the work of journalists can be punished.

But that’s exactly what they do, and we as journalists get nothing or only very little.

You’re facing a wall. Information that should be legally available, isn’t.

As someone who was president of the journalists union, I understand the life of journalists.

Unfortunately, the life of a journalist doesn’t really lend itself to long investigations. The conditions they work in, their salaries and their limited travel options means they often use their own resources to cover the news.

If you’re doing a report two or three kilometers away, you can pay your own way. But don’t even think about doing something 200 or 300 kilometers away! We must improve the salary of journalists.

Nationwide, the average salary of a Togolese journalist isn’t even the minimum monthly wage. [Editor’s note: the minimum wage in Togo is about $70 per month]

So it’s already hard to be a journalist. Let alone to be an investigative journalist.

What was it like working on ICIJ’s most recent project, West Africa Leaks?

It was an opportunity to have access to all the data. [Ed’s note: West Africa Leaks drew on documents from Offshore Leaks, Panama Papers, Swiss Leaks and Paradise Papers]

This is information that is very, very difficult to find anywhere else. It’s an opportunity, even if it’s only a start, and there’s a whole lot of info to find out on the ground.

To know that other people are working on the investigation as you are, is stimulating. You say to yourself, “Alright, I‘m not alone.” It’s healthy competition. I want to do it just as well as the others.

There’s the experience you share with others: learning how one person faced a problem and how they overcame it or how we can help them overcome it.

A community of investigative journalists was born through this investigation. It’s like a family of investigators.

You’re in Togo but you know you have a brother or sister in Burkina, the Ivory Coast, Niger, Chad. There is this friendship that is born, even beyond journalism – a family that is united by the motivation to investigate.