In early 2010, U.S. lawmakers gave what was supposed to be a gift to IRS agents with the grueling job of ensuring the wealthiest people and largest corporations pay their fair share of taxes. Tucked inside President Barack Obama’s landmark Affordable Care Act was a new law that prohibited shifting money around for the sole purpose of avoiding taxes. This struck at the heart of the complex offshore tax maneuvers — the shell companies, sham trusts and dubious intercompany loans — that the affluent use to help keep billions of dollars from government coffers. Suddenly the notion that many of these schemes were technically legal was cast in doubt. Now it was up to the IRS to enforce the new law.

In an era of government cuts and starved social services, this new law — known as the economic substance doctrine — was supposed to help U.S. tax authorities fight the estimated $688 billion a year in unpaid taxes. But then nothing happened. The IRS hardly touched its new weapon against high-end tax evasion — leaving billions of dollars on the table and its agents with little experience in using the law. But why?

An investigation by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists shows how, after coming under pressure from the industries that help wealthy people and corporations avoid taxes, the IRS’s Large Business and International Division, or LB&I, issued a directive that blocked agents from using the economic substance doctrine.

“The IRS had this institutional view not to raise it,” Monte Jackel, a tax attorney who has served several stints as a high-ranking IRS lawyer, said of the economic substance doctrine. “For a decade or so, it was a dead letter — invisible.”

ICIJ found that this IRS directive not only echoed some of the key requests of powerful tax industry players, it also copied several sentences directly from an industry lobbying letter that had urged restrictions on the new law, turning the exact words of tax attorneys for the wealthiest people into official IRS policy. Among those who prepared the lobbying letter were at least four tax attorneys at the corporate law firm Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom, where the IRS official who issued the directive had recently worked. That official, Heather Maloy, has since risen to top brass at the IRS, overseeing all of its enforcement divisions.

A congressional committee estimated that the new tax law was supposed to raise billions in revenue, meaning that the directive may have quietly cost the government large sums.

The reporting adds to growing evidence that LB&I, the office tasked with policing the wealthiest taxpayers, often takes a deferential approach to these powerful players. It also sheds light on the prevalence in the leadership of the IRS and the Treasury Department of tax lawyers who have recently represented the sorts of wealthy taxpayers LB&I is supposed to regulate.

In response to ICIJ’s questions, the IRS emphasized that a recent inspector general report found that the agency did not give large multinational corporations preferential treatment. It also defended its handling of the economic substance doctrine and said that it values input from outside the government. “A cornerstone element of fair and balanced tax administration is allowing those affected by IRS policies to have an opportunity to offer input,” the agency said in an emailed statement to ICIJ. “The tax system cannot operate in a vacuum, and we have a responsibility to give taxpayers the opportunity to be heard as we implement policy.”

ICIJ recently revealed that LB&I applies different and friendlier rules when auditing the wealthy as opposed to small businesses, and that its upper management shies away from even considering egregious tax-dodging cases for criminal referrals. The tiny number of such referrals from LB&I — no more than 22 in a recent span of five years — has frustrated some officials within the IRS’s Criminal Investigation Division, who say they’re often unsupported in identifying cases involving the biggest taxpayers.

President Joe Biden’s administration vowed to tackle high-end tax evasion and secured a historic $80 billion from Congress in part to fulfill this pledge. Now, with this infusion of funding, LB&I is being put to the test. The agency recently made a dramatic reversal in how it regards the economic substance doctrine, touting it as a key tool to stand up to powerful tax cheats.

The IRS now has to play catch-up with its deployment of the doctrine, after letting it gather dust since 2010. At stake are not only billions in government revenue, but also the fate of a key Biden campaign promise to stand up to some of the world’s wealthiest taxpayers.

Fearful of the new law

At least for the richest Americans, avoiding huge amounts of tax often comes down to paying well-heeled accountants and tax attorneys to create complex arrangements that exploit legal loopholes. Corporate tax advisers, though, fear the economic substance doctrine because it can cut through the artificial complexity at the center of many of these schemes.

In the decades leading up to 2010, the economic substance doctrine lived informally in the court system. The government used the doctrine based on case law — i.e., the opinions of previous judges — to cobble together ad hoc and sometimes inconsistent ways of asserting it in tax cases.

Lawmakers saw formalizing the doctrine in federal legislation as a crucial step to strengthen it as a deterrent to high-end tax evasion. The issue united Democrats and Republicans in the belief that the growing tax shelter industry posed a threat to the country’s governance.

For a decade, a group of U.S. senators tried repeatedly to make the doctrine official law and consequently faced fierce opposition from the industry representing private tax advisers. In 2003, then-Sen. Joe Lieberman, D-Conn., said that legislating the doctrine would help fight the “systemic corruption that plagues the accounting, legal and financial communities in the pursuit of tax shelters.” Sen. Chuck Grassley, R-Iowa, a two-time chairman of the tax-writing Senate Finance Committee, declared in 2007 that it was the “right policy.”

Although its enactment into law in 2010 was eclipsed in the news by the larger health-care reform bill, high-end tax advisers quickly took notice.

In public pronouncements, the industry warned that the legislation had ushered in a new world where the codified economic substance doctrine could “dramatically change the tax enforcement landscape.” Just hours after the law passed, the corporate law giant Skadden, which has represented some of the country’s highest-profile tax evaders, warned that it “will have an immediate effect on transactions in the planning stage” and said “taxpayers will need to proceed cautiously.”

The Big Four accounting firms — known to design highly complex structures of offshore shell companies for clients seeking to avoid taxes — also recoiled.

Tax advisers should have difficult conversations with clients and take “a back-to-basics, prudent course,” warned an article in an industry publication co-authored by two tax accountants at accounting giant PwC.

The Big Four firms began trying to shield themselves from the law’s impact, according to documents leaked to ICIJ as part of the Paradise and Pandora Papers. In an agreement to provide tax services to a hedge fund using an entity in the British Virgin Islands, PwC stated it would not be liable for “penalties imposed on you if any portion of a transaction is determined to lack economic substance,” citing the 2010 law. In another tax services contract for a major private equity firm using shell companies in the Cayman Islands, Deloitte said it assumed no “responsibility for any penalties resulting from client’s failure to meet the requirements of the economic substance doctrine.”

Deloitte and PwC did not comment for this story.

The law appeared to be changing the behavior of some of the largest firms. But would this last?

Like Santa Claus

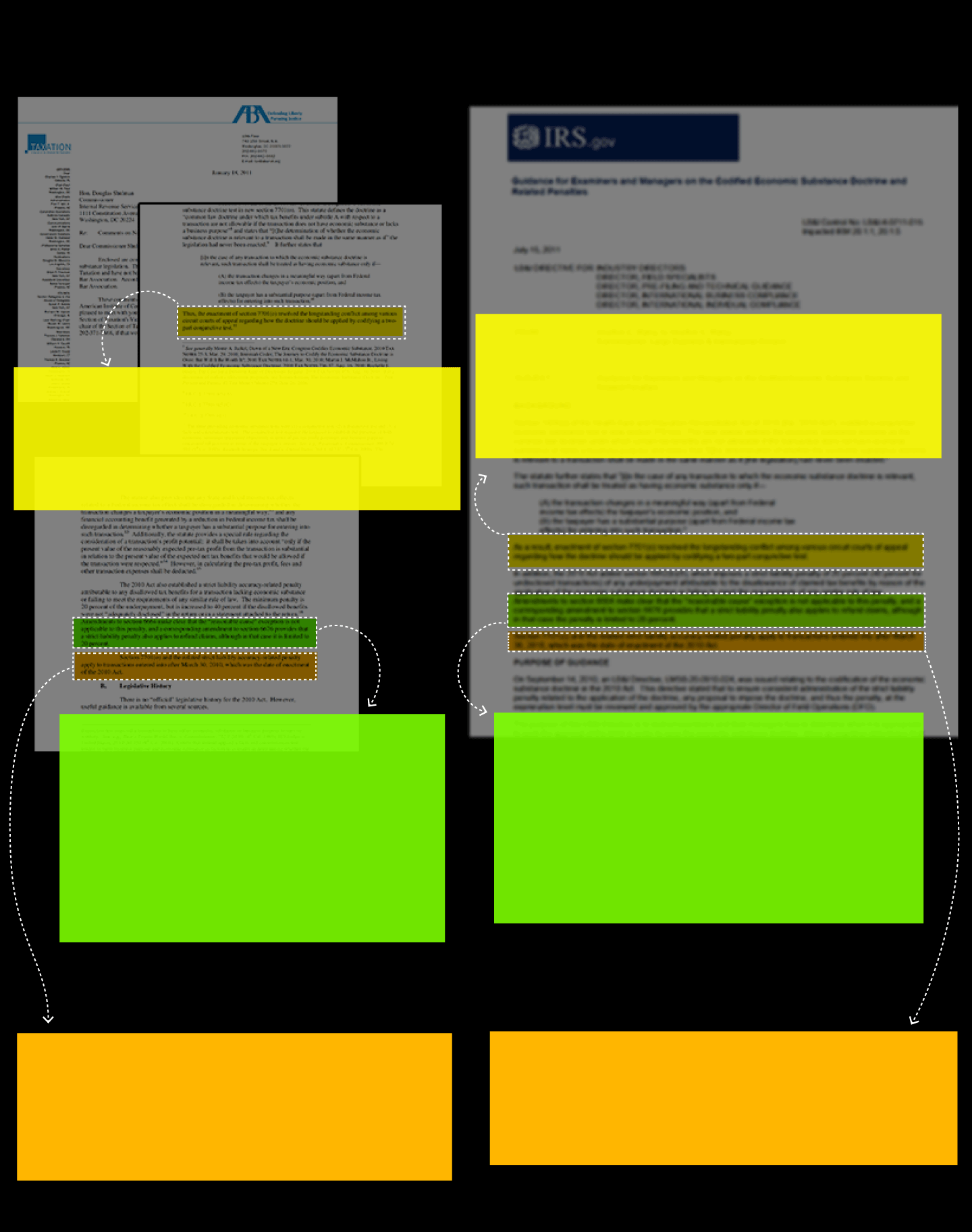

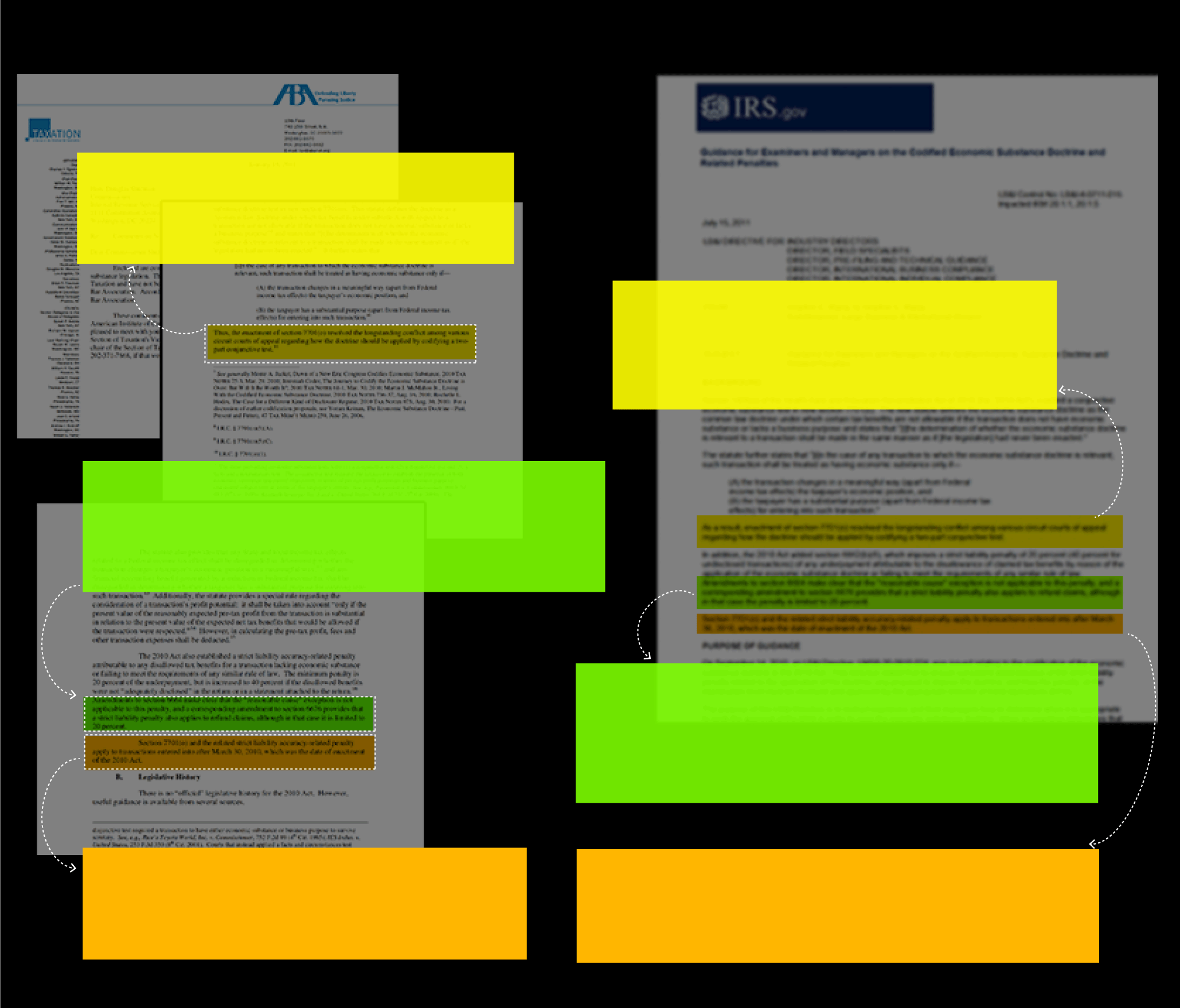

Back in the U.S., the powerful tax law firms that work closely with the Big Four pressed the IRS to restrain its new powers. On Jan. 18, 2011, a group of eminent corporate tax lawyers sent a 66-page letter to then-LB&I Commissioner Maloy and other IRS executives. It urged the IRS to place extensive restrictions on the law that would, in practice, widely obstruct agents’ ability to use it. The letter called the law’s civil fines “a significant stick” and urged the IRS “to be measured in how it swings this stick.”

This letter was written and reviewed by various prominent lawyers, including at least four tax attorneys at Skadden, the firm where Maloy had recently worked as a tax attorney. Two of those were partners at Skadden.

It didn’t take long for the private sector to get what it wanted from LB&I.

On July 15, 2011, Maloy issued a directive that required agents take a series of steps and analyze more than two dozen factors before even asking for approval from a high-ranking IRS executive to use the new law. Agents had to notify the taxpayer as soon as they even considered asking for approval to pursue the economic substance doctrine, and then an IRS executive had to offer the taxpayer a chance to explain their position before the agent could receive approval to use the doctrine. The directive narrowed the scope of penalties agents could seek and defined how agents were generally supposed to analyze transactions — provisions sought by industry.

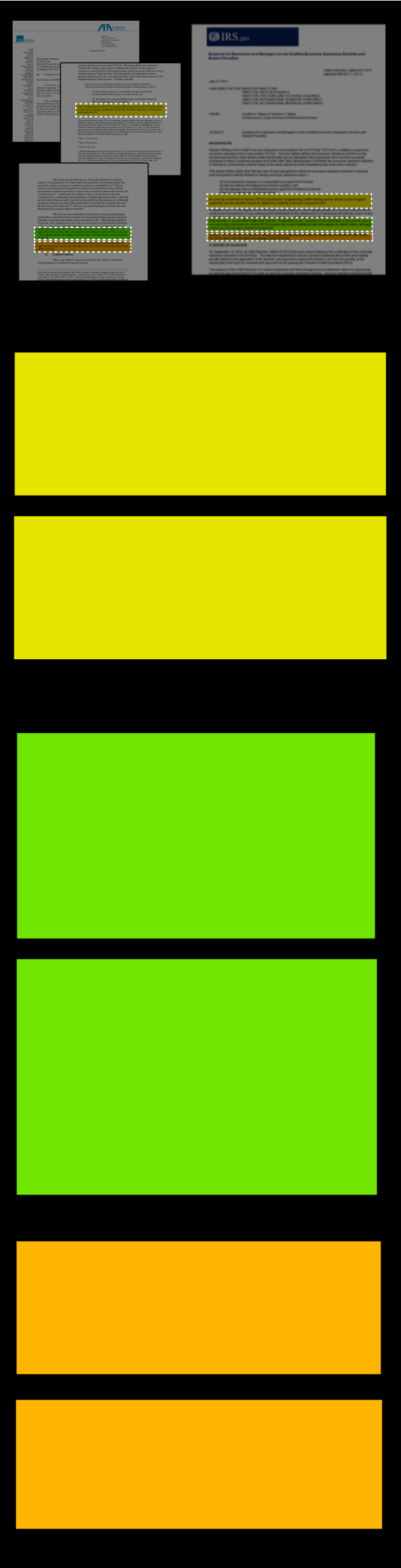

By placing procedural hurdles in the way of using the doctrine, the directive effectively torpedoed a tax law that legislators had fought for a decade to pass. In addition to fulfilling key requests of industry players, the directive copied three sentences directly from the 66-page lobbying letter into official government policy.

Jul. 15, 2011

Jan. 18, 2011

1

1

2

2

3

3

1

... the enactment of section 7701(o) resolved the longstanding conflict among various circuit courts of appeal regarding how the doctrine should be applied by codifying a twopart conjunctive test.

... enactment of section 7701(o) resolved the longstanding conflict among various circuit courts of appeal regarding how the doctrine should be applied by codifying a two-part conjunctive test.

2

Amendments to section 6664 make clear that the “reasonable cause” exception is not applicable to this penalty, and a corresponding amendment to section 6676 provides that a strict liability penalty also applies to refund claims, although in that case it is limited to 20 percent.

Amendments to section 6664 make clear that the “reasonable cause” exception is not applicable to this penalty, and a corresponding amendment to section 6676 provides that a strict liability penalty also applies to refund claims, although in that case the penalty is limited to 20 percent.

3

Section 7701(o) and the related strict liability accuracy-related penalty apply to transactions entered into after March 30, 2010, which was the date of enactment of the 2010 Act.

Section 7701(o) and the related strict liability accuracy-related penalty apply to transactions entered into after March 30, 2010, which was the date of enactment of the 2010 Act.

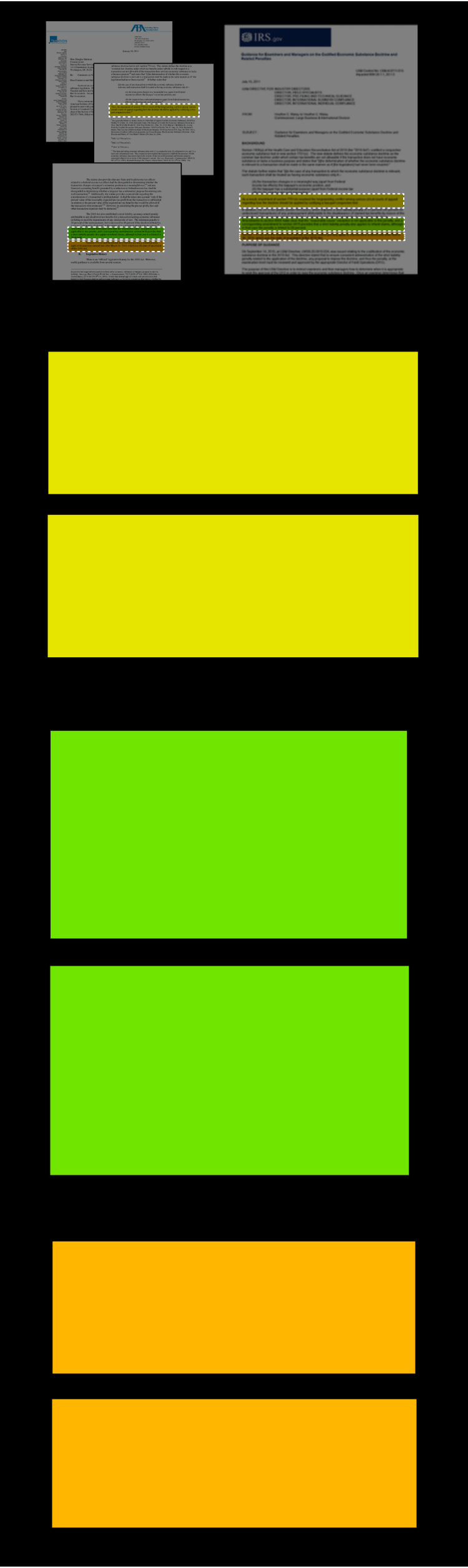

Jul. 15, 2011

Jan. 18, 2011

1

1

2

2

3

3

1

... the enactment of section 7701(o) resolved the longstanding conflict among various circuit courts of appeal regarding how the doctrine should be applied by codifying a twopart conjunctive test.

... enactment of section 7701(o) resolved the longstanding conflict among various circuit courts of appeal regarding how the doctrine should be applied by codifying a two-part conjunctive test.

2

Amendments to section 6664 make clear that the “reasonable cause” exception is not applicable to this penalty, and a corresponding amendment to section 6676 provides that a strict liability penalty also applies to refund claims, although in that case it is limited to 20 percent.

Amendments to section 6664 make clear that the “reasonable cause” exception is not applicable to this penalty, and a corresponding amendment to section 6676 provides that a strict liability penalty also applies to refund claims, although in that case the penalty is limited to 20 percent.

3

Section 7701(o) and the related strict liability accuracy-related penalty apply to transactions entered into after March 30, 2010, which was the date of enactment of the 2010 Act.

Section 7701(o) and the related strict liability accuracy-related penalty apply to transactions entered into after March 30, 2010, which was the date of enactment of the 2010 Act.

Jan. 18, 2011

Jul. 15, 2011

... enactment of section 7701(o) resolved the longstanding conflict among various circuit courts of appeal regarding how the doctrine should be applied by codifying a two-part conjunctive test.

... the enactment of section 7701(o) resolved the longstanding conflict among various circuit courts of appeal regarding how the doctrine should be applied by codifying a twopart conjunctive test.

Amendments to section 6664 make clear that the “reasonable cause” exception is not applicable to this penalty, and a corresponding amendment to section 6676 provides that a strict liability penalty also applies to refund claims, although in that case it is limited to 20 percent.

Amendments to section 6664 make clear that the “reasonable cause” exception is not applicable to this penalty, and a corresponding amendment to section 6676 provides that a strict liability penalty also applies to refund claims, although in that case the penalty is limited to 20 percent.

Section 7701(o) and the related strict liability accuracy-related penalty apply to transactions entered into after March 30, 2010, which was the date of enactment of the 2010 Act.

Section 7701(o) and the related strict liability accuracy-related penalty apply to transactions entered into after March 30, 2010, which was the date of enactment of the 2010 Act.

Jan. 18, 2011

Jul. 15, 2011

the enactment of section 7701(o) resolved the longstanding conflict among various circuit courts of appeal regarding how the doctrine should be applied by codifying a twopart conjunctive test.

... enactment of section 7701(o) resolved the longstanding conflict among various circuit courts of appeal regarding how the doctrine should be applied by codifying a two-part conjunctive test.

Amendments to section 6664 make clear that the “reasonable cause” exception is not applicable to this penalty, and a corresponding amendment to section 6676 provides that a strict liability penalty also applies to refund claims, although in that case it is limited to 20 percent.

Amendments to section 6664 make clear that the “reasonable cause” exception is not applicable to this penalty, and a corresponding amendment to section 6676 provides that a strict liability penalty also applies to refund claims, although in that case the penalty is limited to 20 percent.

Section 7701(o) and the related strict liability accuracy-related penalty apply to transactions entered into after March 30, 2010, which was the date of enactment of the 2010 Act.

Section 7701(o) and the related strict liability accuracy-related penalty apply to transactions entered into after March 30, 2010, which was the date of enactment of the 2010 Act.

High-end tax attorneys celebrated the directive. A news bulletin on one tax law firm’s website trumpeted: “LB&I directive softens economic substance doctrine.” Another firm declared that the steps imposed on agents will likely place “a damper on the number” of cases in which the doctrine could be used.

Industry players themselves “could not have written a more favorable set of audit guidelines than those in the new LB&I Directive,” observed Jasper Cummings, a tax attorney with the law firm Alston & Bird LLP who co-authored the 66-page lobbying letter, in a memo posted to the firm’s website.

“As a result of the Directive recently issued,” Cummings added, “the Economic Substance Doctrine will begin to share a key attribute of Santa Claus: to be more talked about than seen.”

In a memo posted to its website, Skadden described the directive as fulfilling hopes of the industry and said it provided a “welcome assurance” that the new law “will not be asserted without considered review.”

Counsel said the approval process was too burdensome, so they didn’t want to pursue it … They made it administratively impossible to use.

One industry contributor to the 66-page lobbying letter said in a 2018 academic article that as a result of the Maloy directive, the “economic substance doctrine arguably loses any deterrent effect … because taxpayers know that the IRS is unlikely to raise the economic substance issue.”

An LB&I agent who spoke on the condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to speak with the press said he worked on an audit several years ago in which a wealthy individual had dodged millions in taxes through a series of maneuvers that the agent believed could be challenged under the economic substance doctrine. But, the agent said, the July 2011 directive stopped him from using it, partly because of hesitance from the IRS attorneys he worked with.

“Counsel said the approval process was too burdensome, so they didn’t want to pursue it,” the agent told ICIJ.

After this instance, the agent said that he did not try to use the doctrine again: “They made it administratively impossible to use.”

‘A revolving door influence’

For years, watchdogs and lawmakers have expressed concern about the potentially corrupting effects of individuals from the private tax industry ending up in high ranks of the IRS and its parent agency, the Treasury Department. Prominent tax attorneys from Big Four accounting firms or corporate law firms sometimes help implement favorable policies for their former clients. These officials often rejoin the private firms with rapid promotions.

Earlier this year, ICIJ reporting showed that top executives in LB&I commonly switch hats from regulating the wealthiest taxpayers to working for them. A review of LB&I executive lists from the past 13 years shows that out of 114 top executives named, at least a quarter either had worked for a major accounting firm, a tax consulting firm or a major tax law firm shortly before joining the IRS, or left the IRS for such private sector roles.

The IRS’s watchdog, the Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration (TIGTA), warned last year that the movement of employees between the IRS and accounting firms and big companies raised “impartiality concerns.”

As the IRS embarks on a major hiring spree with its new billions, the questions around guarding against industry influence have gained new urgency.

“People from the private sector provide important viewpoints and unique expertise needed to help the IRS run the tax system,” IRS spokesperson Robyn Walker told ICIJ in a statement for a previous story. “This takes on even more importance as the agency works to build compliance work in high-risk corporate and high-wealth areas.”

The agency also told ICIJ that safeguards are in place to prevent conflicts of interest. These rules forbid officials from working on matters too closely related to their work for a former employer in the private sector. Yet these safeguards generally rely on these officials to proactively identify and declare such conflicts to the agency.

In January 2022, TIGTA received an eight-page complaint from an agent alleging that Maloy’s directive had been influenced by the private sector. The complaint alleged that “we at the IRS are not enforcing our tax laws on multinational taxpayers using tax structures lacking economic substance.”

The complaint emphasized that the 66-page letter urging LB&I to restrict the new law was co-authored by attorneys at Skadden, Maloy’s former employer, and alleged that the government was not enforcing its own rules around conflicts of interest.

“There’s clearly a revolving door influence in play within the IRS,” the complaint stated.

“Private sector attorneys from numerous firms known to be involved in promoting, opining, and defending abusive tax structures seized the opportunity to use revolving door colleagues in the executive ranks of the IRS to request, influence and craft guidance,” the complaint also said. The complaint urged the inspector general to assist the IRS in reviewing and revoking the directive.

One of the world’s largest corporate law firms, Skadden has a tax practice that employs a former IRS commissioner and a former executive of LB&I. One of the authors of the 66-page letter, Brendan O’Dell, left Skadden in 2016 to spend six years in high-ranking positions within LB&I and Treasury before becoming the director of tax controversy for Amazon. Another of the letter’s authors, Cary Douglas Pugh, left Skadden in 2014 to become a judge in federal tax court in Washington, D.C., making her among the most powerful people in tax law.

The IRS agent’s complaint to TIGTA has not been previously reported. Michael Welu, a former IRS agent who has been outspoken on the issues he saw within LB&I during his more than three decades at the IRS, provided a copy of the complaint to ICIJ. The complaint’s author, Brian Visalli, is a special agent in the Criminal Investigation Division.

“While I’ll confirm I’m a government whistleblower, I will not confirm or deny any specific complaints or documents I’ve provided to TIGTA,” Visalli told ICIJ in a LinkedIn message. Visalli added that, due to concerns over retaliation, he would not comment further.

In 2015, after almost six years of running LB&I, Maloy left the IRS to become the US Tax Controversy Leader at the Big Four accounting firm EY. EY’s website from that time lists Maloy as a contact in relation to its services around a highly technical practice known as “transfer pricing” that is at the heart of some of the largest tax avoidance schemes.

After five years at EY, Maloy returned to the IRS as a top executive in charge of the entire agency’s compliance efforts. The heads of LB&I, Criminal Investigation and other major compliance divisions now report to her.

ICIJ found that Maloy was not the only government official receiving policy requests from former private-sector colleagues related to the 2010 law. In January 2011, Lisa Zarlenga, then a tax partner at Steptoe & Johnson LLP — a corporate law firm that had opposed to the new law — was named as an author on the 66-page letter requesting restrictions on the IRS’s use of the doctrine. Two of Zarlenga’s colleagues at Steptoe, Mark Silverman and Amanda Varma, were also co-authors of the letter.

But a similar letter co-authored by Silverman and Varma and sent just 3½ months later listed Zarlenga as a recipient. This was because Zarlenga had switched hats to become a high-ranking tax policy official at Treasury.

In an interview with ICIJ, Zarlenga said she had nothing to do with Maloy’s directive. “Treasury would have had no involvement in that directive. I saw it when it was published in Tax Notes along with everyone else.”

In an interview after the the 2011 directive, Silverman — who had helped lead Steptoe’s opposition to the doctrine — called the directive “thoughtful” and “extremely well done.”

Zarlenga, who now heads Steptoe’s Tax Policy Practice, said that it’s both common and important for the industry to weigh in on what the IRS is working on. “Government officials interact pretty regularly with practitioners,” she said. “It’s all part of the flow of information. Otherwise, the government attorneys are sort of sitting in an ivory tower and they don’t know what is going on.”

New life for an old law

Several months after TIGTA received the complaint in 2022, the IRS quietly rolled back the LB&I directive at issue, replacing it with a set of rules that stripped away a number of restrictions on agents’ use of the economic substance doctrine. This was more than a decade after Congress passed the doctrine into law.

The IRS did not respond to requests to comment on this story or answer questions about why it changed its rules around the doctrine in 2022.

Suddenly the industry that had once applauded the directive sounded the alarm once more. In the wake of the new guidance, EY told its clients that “taxpayers should focus on penalty protection” and should consult tax professionals “before entering into transactions with related parties” — a technical term that generally means shifting assets or liabilities between entities all owned by a single person or business.

In a post on its website, corporate law giant Baker McKenzie said the updated directive exemplifies what it called “the IRS’s increasingly offensive posture.”

The law firm was right. In August 2022, Biden signed the Inflation Reduction Act, which included the $80 billion for the IRS to help fulfill his promise to make the wealthiest people and corporations pay their fair share of taxes.

Despite its languid existence after being passed, the 2010 law has become a critical part of this effort. In June, the IRS announced an initiative to tackle tax abuse in the highly complex realm of investment partnerships, which have become a key means for the richest people on Earth to increase their wealth while minimizing the U.S. government’s slice of the pie. In announcing the move, U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen raised eyebrows by stating that “many of these transactions violate the codified economic substance doctrine” — a clear shot at the tax planners serving the ultrawealthy.

Following through on this tougher rhetoric may be difficult, though. Recent ICIJ reporting showed that LB&I often takes an accommodating approach toward the largest taxpayers. Over the past five years, the division flagged no more than 22 instances of possible tax crimes for criminal investigators to review further — out of trillions of dollars in annual income from large corporations and ultrawealthy people that the office oversees. The IRS office that covers small businesses and self-employed people flagged roughly 40 times more possible crimes.

In the agency’s own comments to ICIJ for earlier stories, the IRS suggested that large corporations break the law less often than other types of businesses, saying their checks and balances and their use of independent accountants “generally limit the opportunity for criminal activity.” ICIJ found that the agency treats these powerful taxpayers accordingly.

On Wednesday, TIGTA released an extensive report on the IRS’s challenges to stand up to tax evasion by multinational corporations and addressed frustrations of agents around the difficulty of using the economic substance doctrine. The report also said that the IRS’s 2022 change to the directive was “a result of gaining experience and a level of comfort in the application of the doctrine.” It added that “the IRS could not provide us with the number of cases where examination teams considered the Economic Substance Doctrine.”

The report, which was premised on determining whether the IRS gives multinational corporations preferential treatment, said it found no instances of such treatment. It did, however, recommend that LB&I review its procedures around enforcement of multinational taxpayers, including around its use of the economic substance doctrine.

Experts say that the decade when the doctrine lay dormant may put the office at a disadvantage for a number of reasons. One is that the IRS’s agents and attorneys have little experience using it and could be forced into a trial-and-error approach. Some commentators say that, despite all of the commotion around the law, it may be vulnerable to legal challenges. The previous dearth of cases involving the new law also means that judges are just now getting the chance to issue significant rulings on it. The way judges interpret any tax law sends important signals to the IRS about how to pursue winning legal arguments in court — where they face tax attorneys for large corporations and the ultrawealthy known to spend massively to defeat the IRS.

“They haven’t had a lot of experience in actually applying it in real-world cases or seriously thinking about it,” Jackel, the tax attorney, said of the 2010 law. “It will be a slow process for them to get up to speed on it and be confident in their ability to assert the doctrine.”

Engineering a $2.4 billion deduction

Some of the IRS’s cases using the 2010 law are beginning to make their way through the courts. Most significant of these is the agency’s attempt to invalidate a $2.4 billion tax deduction claimed by Liberty Global, the multinational telecommunications firm led by billionaire John C. Malone. With a net worth of roughly $9.8 billion, Malone is the largest voting shareholder in Liberty Global and is listed by Bloomberg as the second largest private landowner in the U.S., holding some 2 million acres across the country.

In 2020, Liberty Global asked the IRS for a $110 million refund for overpaying its 2018 taxes. The massive refund request was based on a complex series of maneuvers — involving shuffling assets between subsidiaries in places like Belgium, the Netherlands and Slovakia — that had been created by Liberty Global’s tax department with help from Deloitte. In challenging the refund request, Justice Department lawyers alleged that the entire point of the transactions was to improperly exploit a new loophole in federal tax law.

Liberty Global’s tactics did not emerge out of thin air. In one filing, the Justice Department noted that the “situation arises because tax litigators have been developing strategies” like Liberty Global’s. In emails contained in court records, Liberty Global’s tax department discussed paying Deloitte and another Big Four firm, KPMG, hundreds of thousands of dollars for their work on the complex international tax structures. The Justice Department attorneys noted that Skadden had publicly endorsed a refund tactic similar to that of Liberty Global.

Skadden did not respond to a request for comment.

In October 2023, the IRS won its case against Liberty Global, with a federal judge in Colorado ruling that the company’s use of a loophole was not permitted under the 2010 law.

That ruling was “the worst nightmare for tax planners who rely on ‘catching’ Congress in a glitch in the law,” wrote Jasper Cummings, the tax attorney at Alston & Bird. “This Liberty Global opinion is by far the scariest [economic substance doctrine] opinion of recent times and shows a Justice Department unleashed from the historic norms of the income tax.”

Liberty Global maintains that its tax reporting in connection with the case was correct. Although Liberty Global had acknowledged that the maneuvers did not have any true business purpose apart from avoiding taxes, according to court documents, it appealed the ruling in April on technical grounds around applying the doctrine. The firm’s lawyers said “the court fundamentally misunderstood” the case and asserted that the IRS “wrongly wields the economic substance doctrine to rewrite, rather than interpret, the law.”

If Liberty Global prevails in its appeal, it could create a precedent, perhaps as high as with the U.S. Supreme Court, that would weaken the IRS’s use of the doctrine moving forward.

The law firm representing Liberty Global in this quest: Skadden.

Delphine Reuter and Rick Sia contributed to reporting