The United States has fallen behind other developed countries in curbing financial secrecy, surpassing Switzerland as the “international banking center of choice for corrupt transactions,” according to a new report from the University of Sussex.

The findings, based on data that spans four decades and more than 70 jurisdictions, provide “an unprecedented view of how the structure of different types of illicit global financial networks have evolved” in response to changing regulations, the report said.

The researchers identified several long-term trends, including the U.S.’s transformation into a financial transparency scold — and scourge.

Over the past two decades, Washington has successfully lobbied its peers to reform their financial systems while failing to implement similar measures at home, the researchers said.

The U.S. has “been very aggressive at imposing unilateral financial transparency in other places, especially Switzerland, but it really hasn’t reciprocated in banking information exchange,” Daniel Haberly, a professor of human geography at the university who led the research, told ICIJ. “It’s got fairly high financial secrecy, but it also seems to have pretty lax anti-money laundering compliance on top of that.”

Starting around 2013, the researchers said, there was a notable uptick in the use of U.S. bank accounts in bribery cases recorded under the U.S. Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, a law meant to prevent corrupt payments to foreign officials. By comparison, the use of Swiss bank accounts in FCPA cases declined, the report said.

In addition to becoming a more popular conduit for the proceeds of corruption, the U.S. has also become a hub for shell companies, Haberly added, citing states such as Delaware and Florida that have made it easy to set up corporate entities without disclosing the true owners.

As a result, the U.S. in 2022 climbed to the top of advocacy group the Tax Justice Network’s global ranking of “countries most complicit in helping individuals to hide their wealth from the rule of law, earning the worst rating ever recorded since the ranking began in 2009.”

Haberly said another factor in the U.S.’s poor scores on financial secrecy and anti-money laundering compliance was the country’s failure to adopt the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Common Reporting Standard for the automatic exchange of information about financial accounts between jurisdictions. Switzerland is one of more than 100 countries that have adopted the standard since it was developed by the OECD in 2014. Haberly said the subsequent discrepancy in standards is “the most important/relevant factor in the apparent shift in corruption-linked banking from Switzerland to the USA.”

The data used by the University of Sussex researchers goes up to 2023, before the U.S. began implementing its long-awaited registry of company owners this year. But Haberly said the U.S. registry compares poorly to that of other countries because access to the database is restricted to law enforcement agencies, government authorities and financial institutions.

Meanwhile, the United Kingdom has ceased to be a leading destination globally for financial networks in countries looking to avoid sanctions, as a result of years of reforms, the report said. But its network of former colonies, including Hong Kong and Dubai, and overseas territories, such as the British Virgin Islands and Gibraltar, have become more important as offshore tax havens, thanks to their legal systems and close connections to emerging markets that generate significant amounts of illicit funds in addition to the wealth created by their burgeoning legal economies.

“These jurisdictions offer access to English common law and leading Western financial centers and service providers, while falling outside of Western political jurisdiction,” the report said.

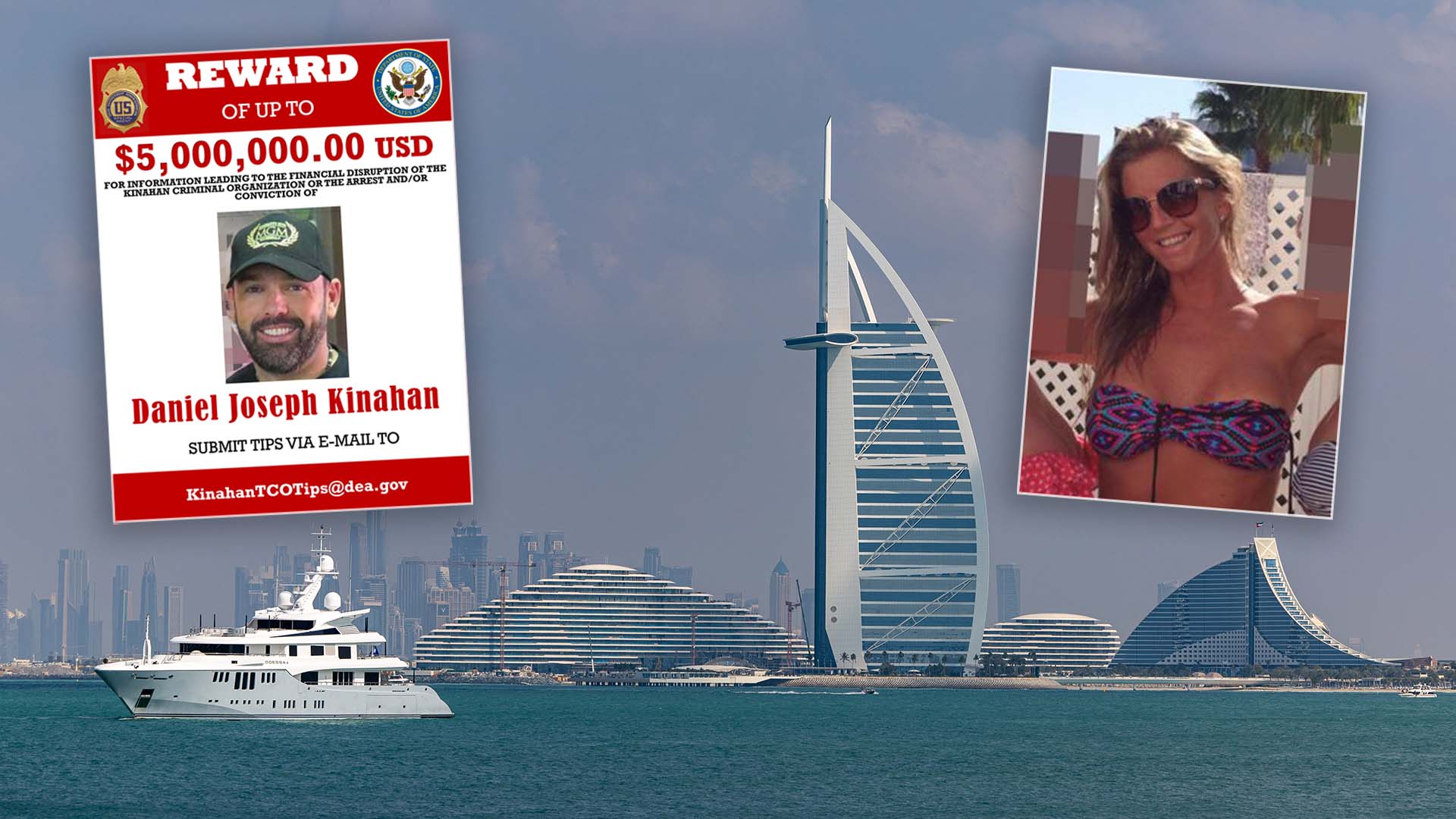

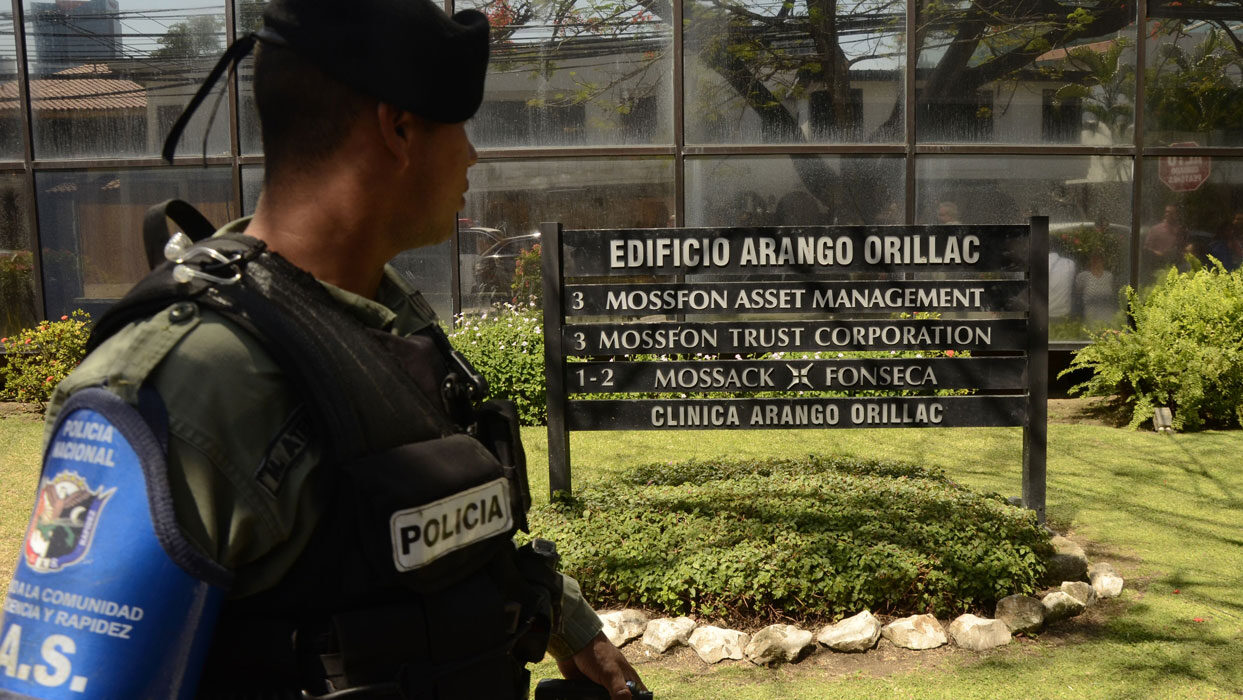

At the same time, the researchers found evidence suggesting organized crime networks increasingly move their money through Hong Kong and Dubai, instead of Panama. Panama’s role as an illicit finance hub has decreased since the publication of ICIJ’s Panama Papers investigation in 2016, replaced by what the researchers dubbed the “Dubai-Kong axis.”

Haberly said that researchers also found “a split” between different types of illicit finance “which seems to be largely based on politics.” Funds linked to corruption and organized crime continue to have connections to the West, chiefly the U.K.’s overseas territories and the U.S., he said, while Russian and Iranian-linked money has found a home in places that have not adopted sanctions, such as Dubai and Hong Kong, which themselves have channels into the global financial system.

The conclusions presented by the academics are based on their analysis of three datasets, containing regulatory data from 70 jurisdictions between 1990 and 2020, information on bank accounts, shell companies and professional middlemen from 262 U.S. foreign bribery cases between 1978 and 2023, and the location of more than 10,000 entities placed under U.S. sanctions, cross-referenced with additional information from other sources.

The researchers also relied in part on leaked data made publicly available by ICIJ following its global investigations, Haberly said, as well as samples from the Tax Justice Network. The paper found that “anti-corruption initiatives” across the jurisdictions tended to be led not by governments but by NGOs and journalists. Haberly said official institutions should collaborate more with investigative media and grant wider access to data for journalists.