PRESS FREEDOM

‘Many journalists have left’: How post-election repression compounded press freedom fears in Venezuela

Since the presidential campaigns started, at least eight journalists were imprisoned in Venezuela — an intimidation tactic that makes investigative reporting harder for independent news outlets such as Armando.Info, an ICIJ partner.

On July 20, Joseph Poliszuk and his colleagues celebrated the 10th anniversary of Armando.Info, a Venezuelan investigative news outlet he co-founded. The ICIJ partner had survived threats and censorship and was preparing to cover the Latin American country’s presidential election eight days later. Like other journalists there, Poliszuk and his team were worried repression could become more intense and hoped their jobs would not become even harder.

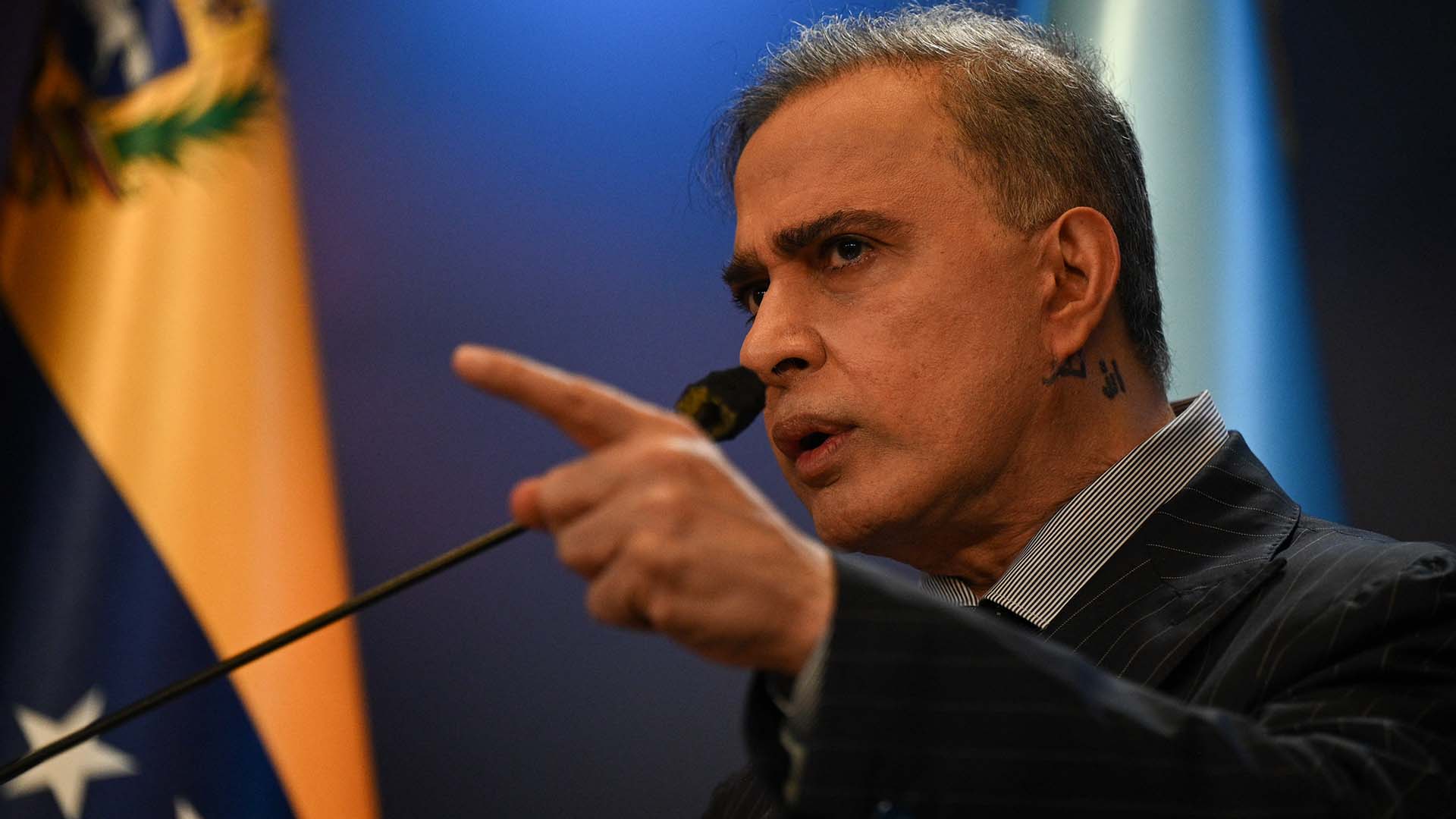

President Nicolás Maduro was reelected, but the results were disputed by Venezuela’s opposition party, which claimed to have proof their candidate won. This sparked protests against Maduro’s victory across the country which the government reacted to with the “harshest and most violent” repression tools, according to a report published by the U.N.-backed Human Rights Council. The report said that a fact-finding mission had found rights violations including arbitrary detentions, torture, and sexual and gender-based violence by law enforcement. Venezuela’s National Electoral Council said in a press release that the report was “illegal, contrary to the principles of the UN, violating the Terms of Reference agreed with this Constitutional Power and, above all, riddled with lies and contradictions.”

Journalists faced their own set of targeted threats, Poliszuk told ICIJ. “After the elections, the government canceled passports, not only of journalists, but of activists and political leaders as well,” he said. “It was a pressure and censorship tactic that sent the message ‘you are on the list, you better watch yourself.’”

As a precaution, Poliszuk said his team helped two Armando.Info reporters based in Caracas, the capital city, temporarily leave the country. This made reporting harder. Armando.Info has operated a hybrid newsroom since early 2018, when a handful of its journalists had to flee the country after they were sued by a business executive they exposed as having ties to Maduro’s political party. Currently, half of the team works remotely from outside Venezuela.

“Some are referring to it as ‘journalism in exile’ and I think it has been romanticized a lot,” Poliszuk said. “Of course, it is great that technology has allowed us to come up with methodologies to continue this work from the outside — something that was not an option during past dictatorships in the 20th century. But it is not ideal. We lose timing, we lose reporting from the streets, we lose sources.”

The trade-off is security, he said. Poliszuck found a home in Mexico, an unlikely refuge as one of the most dangerous places in the world for journalists, according to the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. “It appears that the modus operandi in Venezuela is to jail journalists, while here they are murdered,” Poliszuk said. “We all follow some basic security measures. I feel much safer here than even in Colombia. Not because Mexico is safer, but because the interests I touch are not here.”

Meanwhile, in Venezuela, at least 10 journalists have been arrested since the recent electoral campaigns began, and eight remain in prison “under false charges and in worrying conditions,” according to Reporters Without Borders, which advocates for freedom of information. Half of those were arrested during the post-election protests. State-orchestrated censorship and disinformation campaigns, which reportedly intensified around the elections, have compounded the challenges faced by reporters and citizens in Venezuela. Rolling blackouts, intermittent water supply and limited internet bandwidth already made reporting hard, Poliszuk said. The Committee to Protect Journalists found that since the election, reporters had self-censored, not appeared on camera and avoided attending or covering opposition rallies. Some radio news programs went off the air, the press freedom organization reported.

Armando.Info, a long-term ICIJ partner that has worked on investigations such as the Panama Papers and Paradise Papers, also stopped publishing bylines for months after the election to protect their identities. Journalists’ identities became especially sensitive during the post-electoral unrest as the Government brought back a repression tactic first introduced in 2017 dubbed “Operación Tun Tun,” or “Operation Knock Knock,” as has been reported by Armando.Info and several international outlets.

The “operation,” as it was described in at least one social media post by an account run by the military, consists of identifying those who speak negatively about the government, knocking on their door and detaining them. Armando.Info has labeled the tactic “lynching 2.0 of opponents.”

The Venezuelan non-governmental organization Foro Penal published a report last week that counted 1,848 political detainees since election day on July 28. Twenty-four people have been murdered in the same period amid social unrest, according to Human Rights Watch.

“Many journalists have left, others are afraid, and for others, their outlets do not have the resources to pay them,” said Poliszuk. “The effort we make goes beyond the news-making process.”