ICIJ MEMBERS

ICIJ member’s new book explores unexamined but influential WWII spy

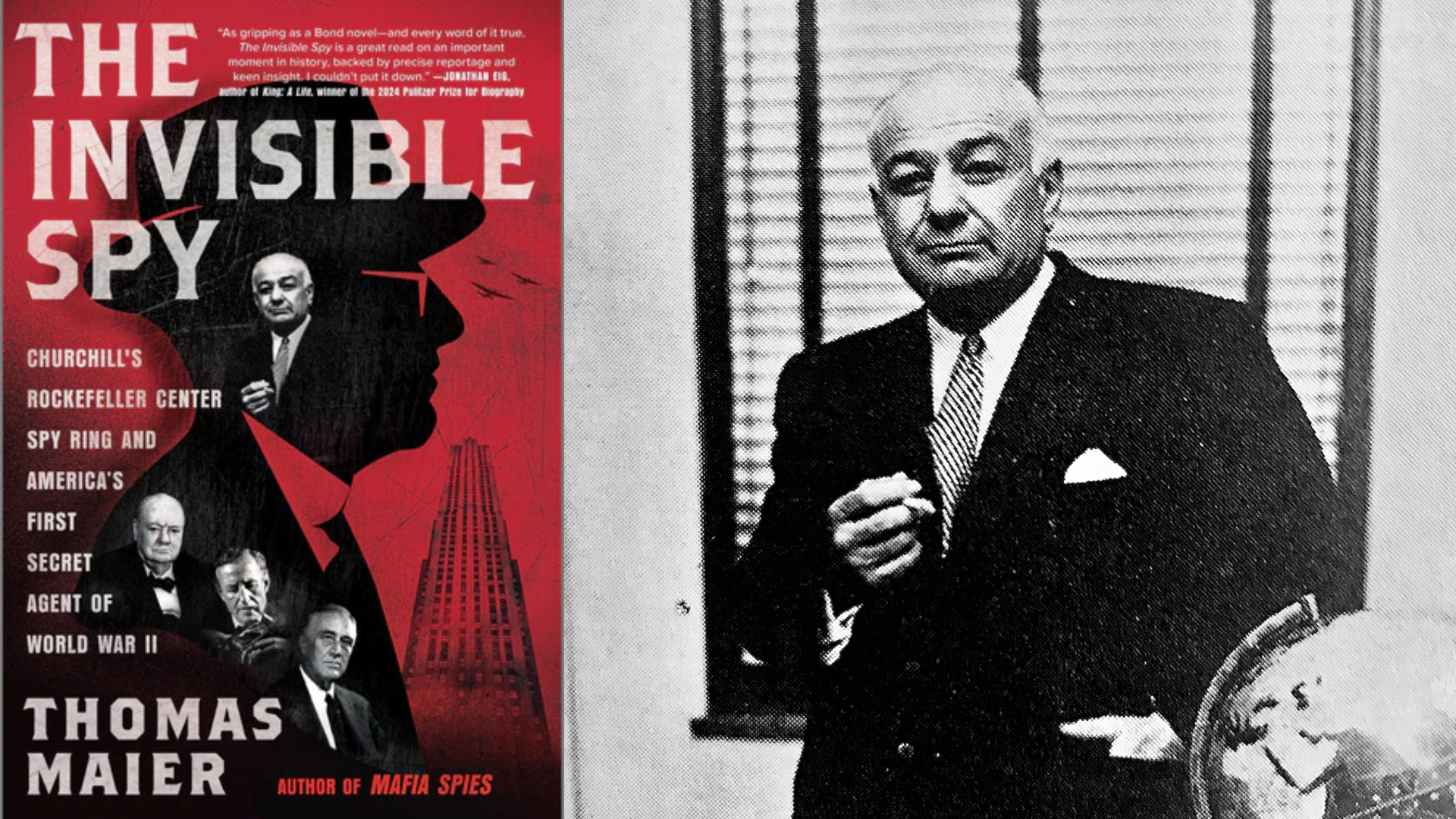

Thomas Maier’s latest release, “The Invisible Spy,” revisits the cinematic life of real-life U.S. intelligence officer Ernest Cuneo.

A National Football League player. A lawyer to 20th-century media celebrities. A Washington insider. And an American spy who helped orchestrate one of the largest foreign espionage operations ever conducted in the United States.

Ernest Cuneo — a figure in American history who has, until now, mostly flown under the radar — embodied all these personas.

“The Invisible Spy,” a new book by investigative journalist and ICIJ member Thomas Maier, tells Cuneo’s story for the first time, revealing the life of one of the most powerful spies of the World War II era.

A longtime reporter for Newsday, Maier twice won the National Society of Professional Journalists’ Sigma Award — once for his work on Skin & Bone, an ICIJ investigation examining the lucrative international market for recycling corpses into medical implants. He also won ICIJ’s Daniel Pearl Award in 2002 for his investigative work on immigrant workplace deaths. Since then, Maier has produced the Emmy-winning TV series “Masters of Sex” and the 2024 docuseries “Mafia Spies,” both adapted from his nonfiction books.

ICIJ spoke with Maier about his latest book — set to release on March 25 — on some of the power players of World War II, and why audiences and researchers alike continue to gravitate toward the subject of espionage.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Can you tell me a bit about the genesis of this new book? Where did your interests in Cuneo and this portion of history begin?

Ten years ago, I wrote a book about the Churchills and the Kennedys called “When Lions Roar,” and in doing that book, I became aware that there had been a group of spies that had been put up on the 36th floor of Rockefeller Center by Churchill, virtually right after he took power as prime minister. On a personal note, Rockefeller Center is a place where a lot of good things have happened to me both personally and career wise. I actually proposed to my wife, Joyce, in 1983 underneath the Christmas tree of the Rockefeller Center.

It wasn’t until I knew about Ernest Cuneo that I saw a thread, if you will, that went through a number of different spy cases in which Cuneo was either directly involved or indirectly involved by virtue of his very influential position within the government. And so I realized that Cuneo was, in today’s parlance, a “Deep State figure.” I mean, he was a person who was very much involved in the intelligence services as they were in the early days of espionage for the United States. But he was also involved politically. He was also the counsel, the lawyer for two of the top media personalities, in particular, Walter Winchell.

This is not like my other biographies that have been focused on “great men” like Winston Churchill. This was somebody that nobody really knew about, and Cuneo deliberately tried to keep his anonymity. So that challenge of doing a book, not about a great man, but a person who wanted to be an anonymous man — an invisible spy — to try to tell that biography was, to me, a really intriguing challenge.

What were you able to glean throughout the process of your research on Cuneo’s personality?

Well, he was an Italian American fellow from New Jersey who went to Columbia University. [He] was very aware, back a hundred years ago in the 1930s, of being an Italian American and realizing that the upper rungs of power in this country, it was still essentially the realm of white Anglo Saxon Protestants. So I thought that was interesting, his outsider perspective.

There were articles in the New York Times about him being a prominent wrestler, and he was also a football player at Columbia, and then he played in the NFL. For a while, he was very much enchanted with the idea of fame. But as he matured, he realized that he was much more effective being anonymous or by being invisible, by being in the background.

Why do you think Cuneo has eluded more extensive retrospection of his life before now?

Like several people of his generation or people that were involved in spying, it was a point of honor, but it was also a point of the law not to speak about espionage. If you were a British spy, there was the Official Secrets Act. Even within the United States, where there was a little bit more freedom, it was a point of honor that you didn’t talk about these things. For Ian Fleming, the way for him to kind of recreate and relive his experiences as a spy in World War II was the creation of James Bond. He did it fictionally. In fact, Casino Royale, as I describe in my book, has a couple of scenes that came right out of Fleming’s own experiences that were changed around for matters of fiction.

You were telling me a bit about Fleming turning his own experiences into the Bond novels. I’m wondering if you can tell me a bit about Cuneo and Fleming’s relationship, and more broadly, share your thoughts on our enduring fascination with espionage as a subject matter.

They were kind of opposites. Cuneo was an Italian American from the New York area. Cuneo was a very different man than Fleming. Fleming was more acerbic. He had a sardonic sense of humor, but they both liked women. They both liked to go out for drinks. They both were intrigued by this thrilling experience of being spies during the most formative time period of their whole generation: World War II.

The second question, why are we so fascinated with espionage? Well, human beings have always been intrigued by secrets, by heroics in the shadows. The idea that there are deep state figures who may actually be people who help save us from dangers that we’re not aware of.

This book was an opportunity to kind of explore the origins of American espionage, and do it through the realm, not of some well known politician, but through the eyes and the experiences of a man in the middle of all of this. A man who was a fixer, who was a lawyer, who was an advocate, a man who would place plant stories in some of the top media outlets of his time to give his spin on stories.

He was invisible, and he realized that the key to his effectiveness, his influence with people, was that anonymity.