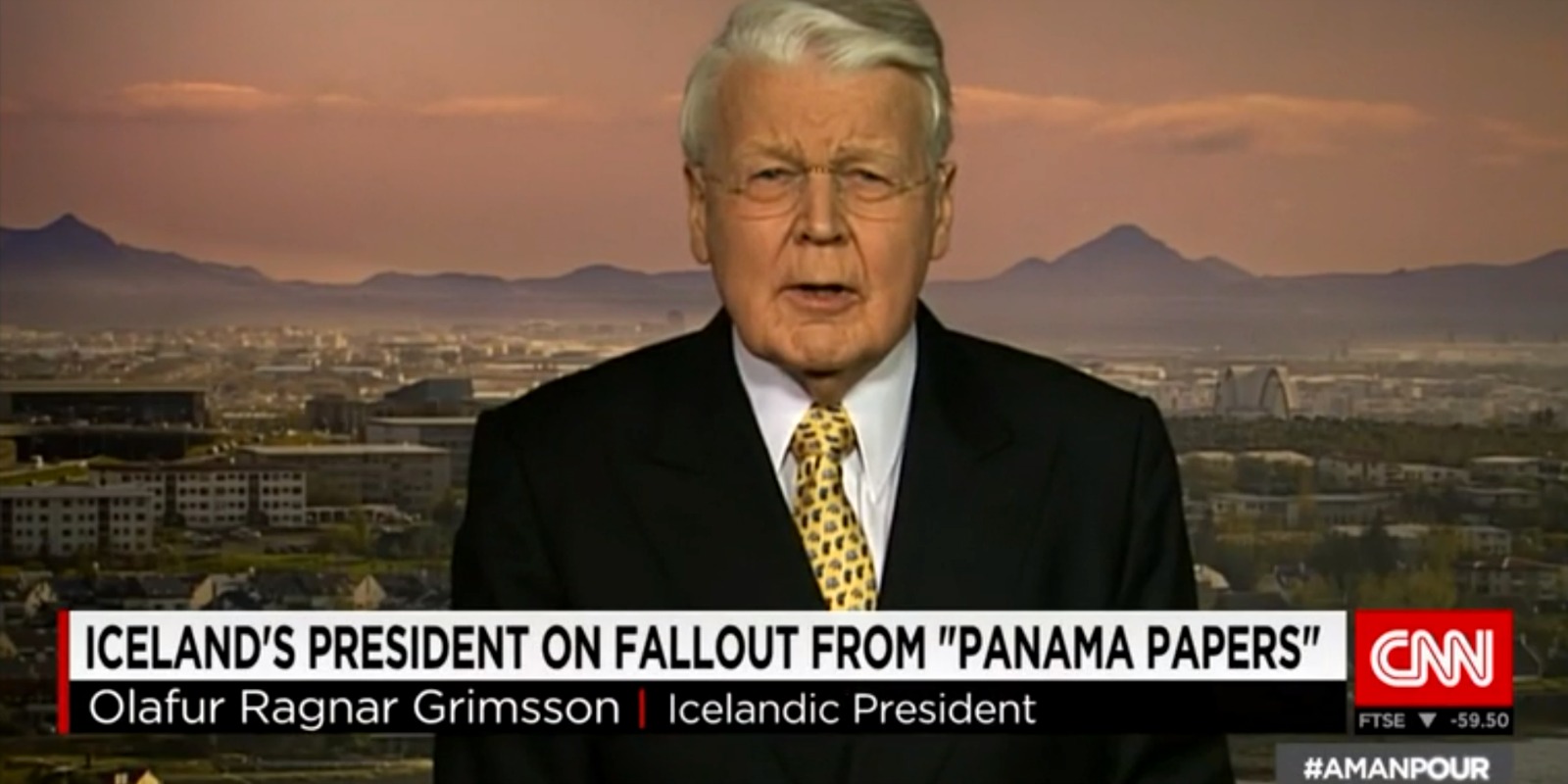

On April 22, CNN’s Christiane Amanpour asked Iceland President Ólafur Grímsson: “Do you have any offshore accounts? Does your wife have any offshore accounts? Is there anything that’s going to be discovered about you and your family?”

“No, no, no, no, no,” Grímsson replied. “That’s not going to be the case.”

But secret records obtained by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and other media partners show that Grímsson’s spouse, First Lady Dorrit Moussaieff, has had extensive links to the offshore world.

While Grímsson himself doesn't have an offshore account in the records, First Lady Moussaieff was listed as a beneficiary of five companies and trusts that have held Swiss banks accounts, according to documents obtained from whistleblowers by Le Monde, Suddeutsche Zeitung and ICIJ in the Swiss Leaks and Panama Papers investigations. Her family, including her two sisters, had accounts that together held as much as $80 million in HSBC’s Swiss Private Bank in 2006 and 2007. Dorrit Moussaieff herself appears not to have played a role in most of the holdings.

The documents don’t show any wrongdoing by Dorrit Moussaieff, and it is not necessarily illegal to have offshore companies or Swiss bank accounts. But the documents raise questions about whether Iceland’s first lady benefited from the offshore tax strategies of her parents and whether her interests have been fully disclosed.

Earlier revelations about the offshore holdings of Prime Minister Sigmundur David Gunnlaugsson had forced the prime minister’s resignation. Grímsson explained his about-face on running for his sixth term as president by saying he wanted to bring some stability to a country that suffered a financial collapse in 2008 and is now going through a political crisis.

Later in the CNN interview, Grímsson called the Panama Papers “a great public service” and “a wakeup call” about problems in the global economy that need to be addressed.

In a statement to ICIJ, a spokesman for Grímsson said: “President Grímsson does not have, nor has he at any time had, any information about the financial affairs of his wife or other members of the Moussaieff family. He and his wife lead independent lives.”

In a statement to The Guardian, another ICIJ media partner, Grímsson noted that he has “always been very critical of tax-driven offshore structures and for decades advocated a fair and balanced tax system.”

In a letter to ICIJ, the first lady’s law firm wrote: “Ms. Moussaieff and her husband have always and continue to conduct their financial affairs entirely separately from each other and neither has knowledge of the other’s financial circumstances. Ms. Moussaieff’s private financial affairs are conducted in compliance with all relevant tax and legal regimes. Any insinuation to the contrary would be defamatory.”

“There is no public interest in the disclosure of private financial information,” the letter said.

Several of the structures set up through HSBC and Mossack Fonseca by members of her family are trusts. For instance, HSBC listed the first lady as the both the settlor and beneficiary, along with her two sisters, of Jaywick Properties Inc. and the Moussaieff Sharon Trust. The first lady was also a secondary beneficiary of Elyakeen Limited, the Moussaieff Life Interest Trust and Easton Investments Inc.

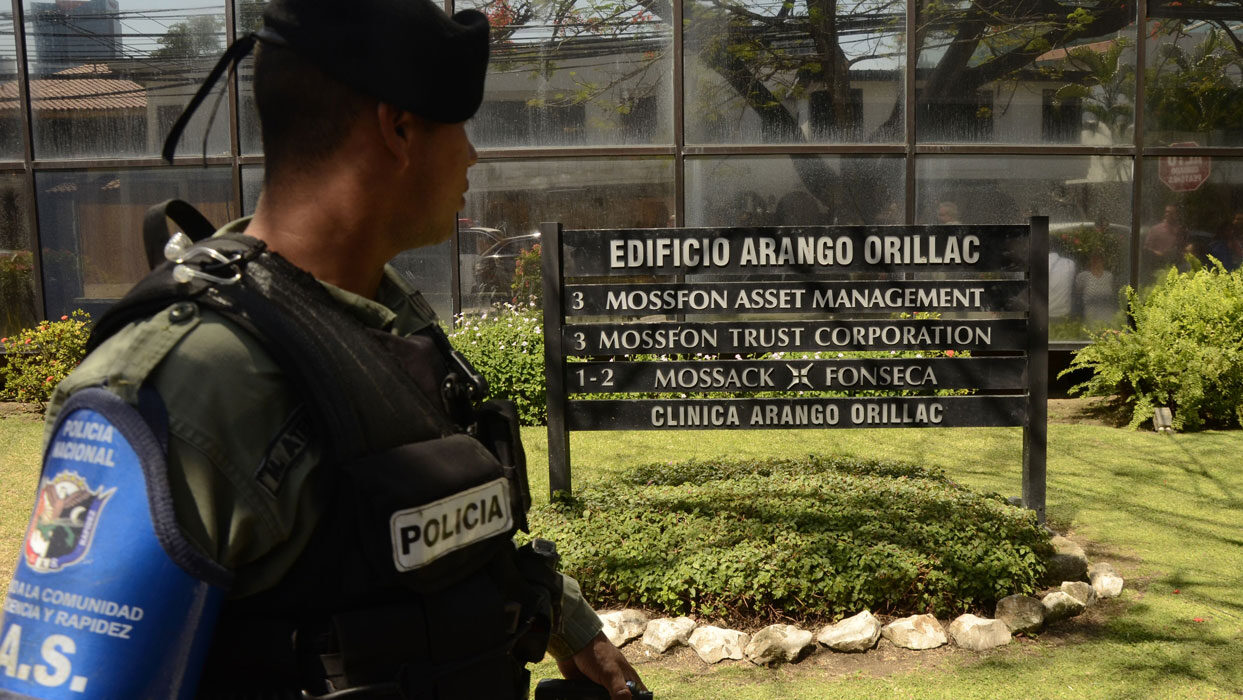

Elyakeen Limited was registered with Mossack Fonseca in the British Virgin Islands in 1995. Its stock was in bearer shares, certificates that allow whoever holds the paper to anonymously transfer or claim their value. Today they are banned in many countries because of their usefulness in aiding money laundering and tax evasion.

A settlor is the person who transfers control of assets to a trustee, who manages them on behalf of the beneficiaries, which, in some trusts, may include the settlor. Trusts can make it easier to transfer assets after death, eliminate probate costs and reduce estate taxes.

Both of Dorrit Moussaieff’s sisters — but not the first lady — had large trusts in their names at HSBC’s Swiss bank. The Tamara Moussaieff Trust held $29.5 million at one point in 2006 and 2007, while one owned by Sharon Levontin, called Levontin 2002 Discret Sett, held $27.6 million in the same period. HSBC documents also include the Mrs S Levontin Trust, which at one point in 2006 and 2007 held $2 million in six accounts at the bank.

The Elyakeen bearer shares were held for the Moussaieffs by a Zurich trust management company. In 1999, the directors opened bank accounts in Elyakeen’s name at Deutsche Bank and at the Royal Bank of Scotland. Elyakeen was dissolved in 2003. Elyakeen’s HSBC profile was created in 1997.

It is unclear how much money was in Elyakeen’s accounts, but one Mossack Fonseca document dated April 4, 2002, shows significant sums. “The Directors had been approached by the trustees to consider waiving the loan of ($18.8 million) repayable by them, following tax advice from KPMG,” according to the minutes of the board meeting. Elyakeen also paid out a $1.6 million dividend at that meeting.

Reykjavik Grapevine reported on April 25 that the Moussaieff family had another company registered with Mossack Fonseca in the British Virgin Islands. That company, Lasca Finance Limited, was disclosed in public filings of Moussaieff Jewellers Limited, the family firm.

“Neither the President nor his wife, Dorrit Moussaieff, has any knowledge of this company or had heard about it before,” Grímsson’s spokesman said in a statement. “Dorrit's father is no longer alive, and her mother, who is 86, has no recollection of this company.”

Alisa and Tamara Moussaieff and Sharon Levontin did not respond to requests for comment.