China’s mass detention of Uighurs and other ethnic minorities living in its western region of Xinjiang has sparked alarm and condemnation across the world. Now, for the first time, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists’ China Cables investigation has revealed classified Chinese government directives that provided operational plans for the internment camps and orders for carrying out mass detentions guided by sweeping data collection and artificial intelligence.

To better explain China’s actions in Xinjiang and the findings of the China Cables, we answer some key questions about who is involved, the crackdown’s origins, and the significance of the secret documents.

Who are the Uighurs?

The Uighurs are a Turkic ethnic group whose members are predominantly Muslim. Uighurs have a distinct culture and history, including the declaration of two short-lived independent republics, both known as East Turkestan, in the first half of the 20th century.

Nearly 11 million Uighurs live in Xinjiang in the far northwest of China, an arid region of mountains and expansive steppes. Smaller groups are found across Central Asia. Scholars say Uighur identity developed over centuries around oasis towns.

What is happening to the Uighurs?

In recent years, the Chinese government has launched a crackdown on Uighurs and other ethnic minorities in Xinjiang, including sweeping surveillance, mass detentions and forced assimilation. Video cameras and police checkpoints keep citizens under constant watch. The United States government has estimated that more than a million Uighurs – representing nearly 10 percent of the Uighur population in Xinjiang – have been locked up by Chinese authorities.

U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo has denounced China’s treatment of Uighurs as the “stain of the century.”

Why is the Chinese government persecuting Uighurs?

China says that the crackdown is necessary to prevent terrorism and root out Islamic extremism. The action is part of a larger campaign by Chinese leader Xi Jinping to promote Han nationalism as a unifying force – the Han are China’s ethnic majority – and to suppress any ethnic, cultural or religious identities that might compete for popular loyalty with the Chinese Communist Party.

In 2009, tensions fueled by decades of institutionalized discrimination and marginalization against Uighurs in their own homeland exploded into violence in the streets of Xinjiang’s capital, Urumqi. Clashes between Uighurs and Han Chinese killed some 200 people, who authorities said were mostly Han. China blamed Uighur separatists and has vowed to eliminate separatist and militant Islamic ideology among the Uighur population.

What are the Chinese government’s re-education camps?

Starting in 2017, many Uighur detainees have been sent to camps the government calls “Vocational Education and Training Centers.” There, detainees are forced to learn Mandarin, renounce “extremist” thoughts and undergo daily indoctrination in Chinese Communist Party propaganda. Some former detainees say they suffered torture and sexual abuse.

Detainees are also given vocational training, and after completing the indoctrination program, are assigned to factories to work under conditions widely considered to be forced labor.

How has the rest of the world responded?

The United States has provided the most forceful response, announcing sanctions in October against Chinese entities and officials linked to repression in Xinjiang. Among the 28 entities blacklisted were the giant Chinese video surveillance companies Hikvision and Dahua, as well as numerous Chinese state offices. The officials targeted with visa restrictions have not been publicly identified.

In a letter to the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights in July, nearly two dozen industrialized countries called on China to end the mass detention program.

Sweden announced that it will grant refugee status to China’s Uighurs in 2019.

However, a number of Western multinationals, including the German conglomerate Siemens AG, have maintained business ties with Chinese entities linked to the Xinjiang crackdown. In a statement to ICIJ’s partners at the German public broadcaster NDR, Siemens said its cooperation with the state-owned military contractor China Electronics Technology Group Corporation focused on “intelligent manufacturing solutions” and that it “does not supply any products that are used in the end products of our customer.”

What does China say about the camps?

In a statement to ICIJ’s media partner The Guardian, China said the camps are an effective tool in its fight against terrorism and do not infringe on religious liberty.

“Since the measures have been taken, there’s no single terrorist incident in the past three years. Xinjiang again turns into a prosperous, beautiful and peaceful region,” according to the statement, issued by the press office of China’s embassy to the United Kingdom. “The preventative measures have nothing to do with the eradication of religious groups. Religious freedom is fully respected in Xinjiang.”

China also disputed the authenticity of the leaked documents, calling them “pure fabrication and fake news.” It referred to an official White Paper in which the Chinese government describes the camps’ purpose as providing aid and rehabilitation for those involved in terrorist or extremist activities.

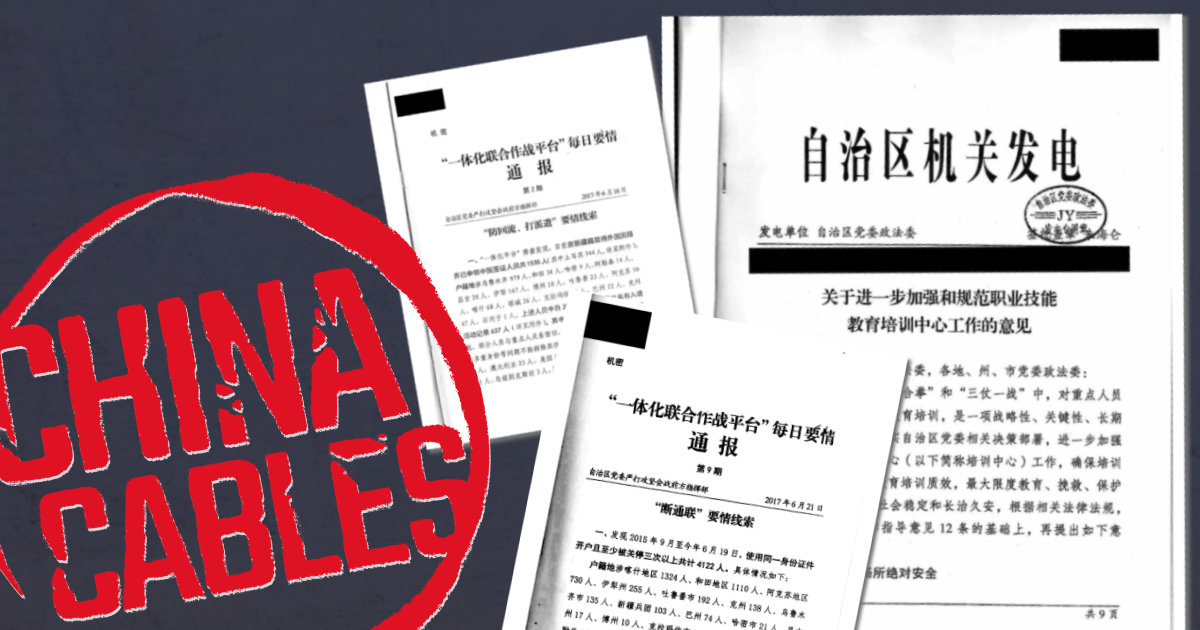

Telegram

This telegram is from the Communist Party commission in charge of Xinjiang’s security apparatus. The telegram, written in Chinese, is an operations manual for running the mass detention camps. It is marked “secret” and was approved by Zhu Hailun, then deputy secretary of Xinjiang’s Communist Party and the region’s top security official.

Telegram

This telegram is from the Communist Party commission in charge of Xinjiang’s security apparatus. The telegram, written in Chinese, is an operations manual for running the mass detention camps. It is marked “secret” and was approved by Zhu Hailun, then deputy secretary of Xinjiang’s Communist Party and the region’s top security official.

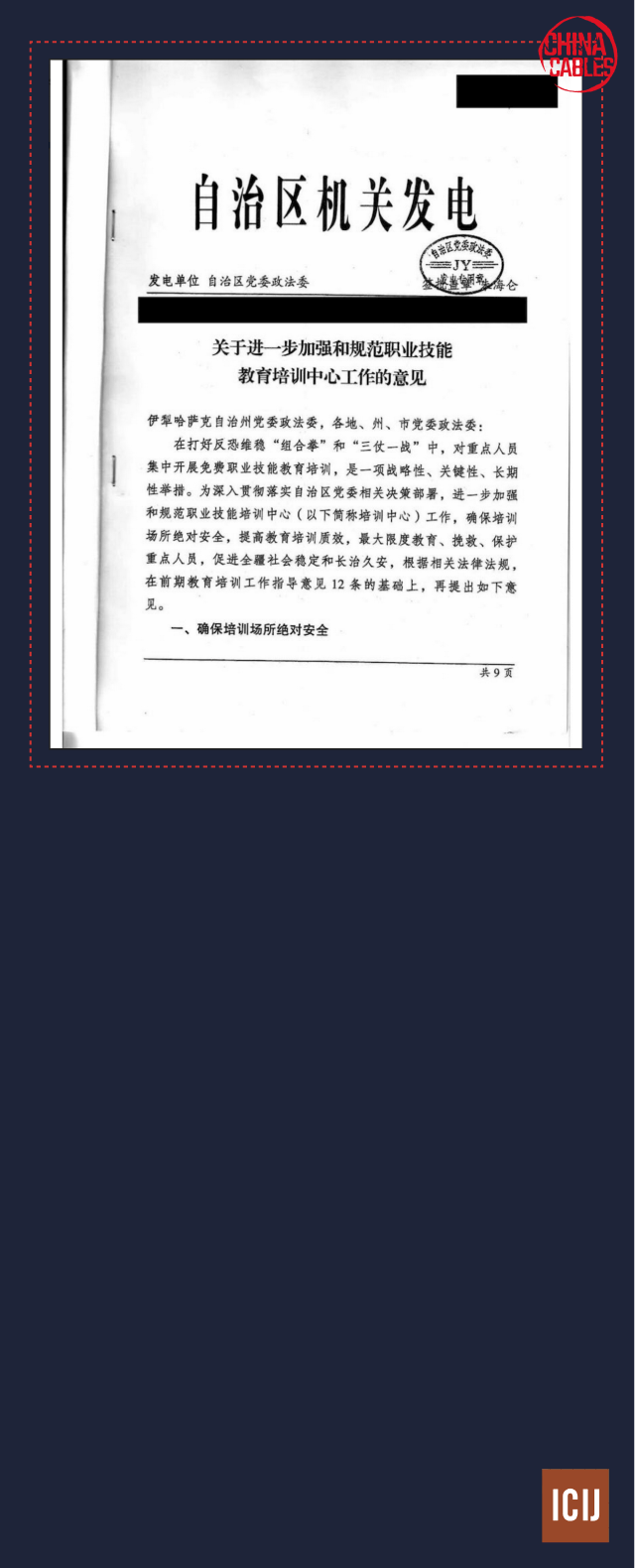

Telegram

This telegram is from the Communist Party commission in charge of Xinjiang’s security apparatus. The telegram, written in Chinese, is an operations manual for running the mass detention camps. It is marked “secret” and was approved by Zhu Hailun, then deputy secretary of Xinjiang’s Communist Party and the region’s top security official.

Telegram

This telegram is from the Communist Party commission in charge of Xinjiang’s security apparatus. The telegram, written in Chinese, is an operations manual for running the mass detention camps. It is marked “secret” and was approved by Zhu Hailun, then deputy secretary of Xinjiang’s Communist Party and the region’s top security official.

What documents were obtained for the China Files investigation?

The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists has obtained highly confidential Chinese government documents detailing the official policies behind the Xinjiang camps.

The China Cables documents include a detailed 2017 manual setting out guidelines for personnel running the camps, including security protocols, methods of monitoring and controlling detainees, camp curriculum and criteria for release. They also include four intelligence briefings, known as “bulletins,” setting out policies for identifying and rounding up Xinjiang citizens targeted for detention.

The manual was issued by Xinjiang’s Political and Legal Affairs Commission, the Chinese Communist Party body in charge of the region’s security apparatus, and the bulletins by the Xinjiang Communist Party’s “Forward Command for the Strike Hard Assault Battle” Committee, which helped implement the security crackdown. All of the documents are signed by Zhu Hailun, who at the time was Xinjiang’s top security official and deputy Communist party chief.

The documents also include the judgment from a court case in Xinjiang in which a Muslim man was sentenced to ten years in prison for advocating Islamic religious practices. Among the actions he was punished for were telling co-workers not to use profanity or watch pornography.

Linguists and experts who reviewed the documents have expressed a high degree of confidence in their authenticity. Former detainees have also corroborated their contents.

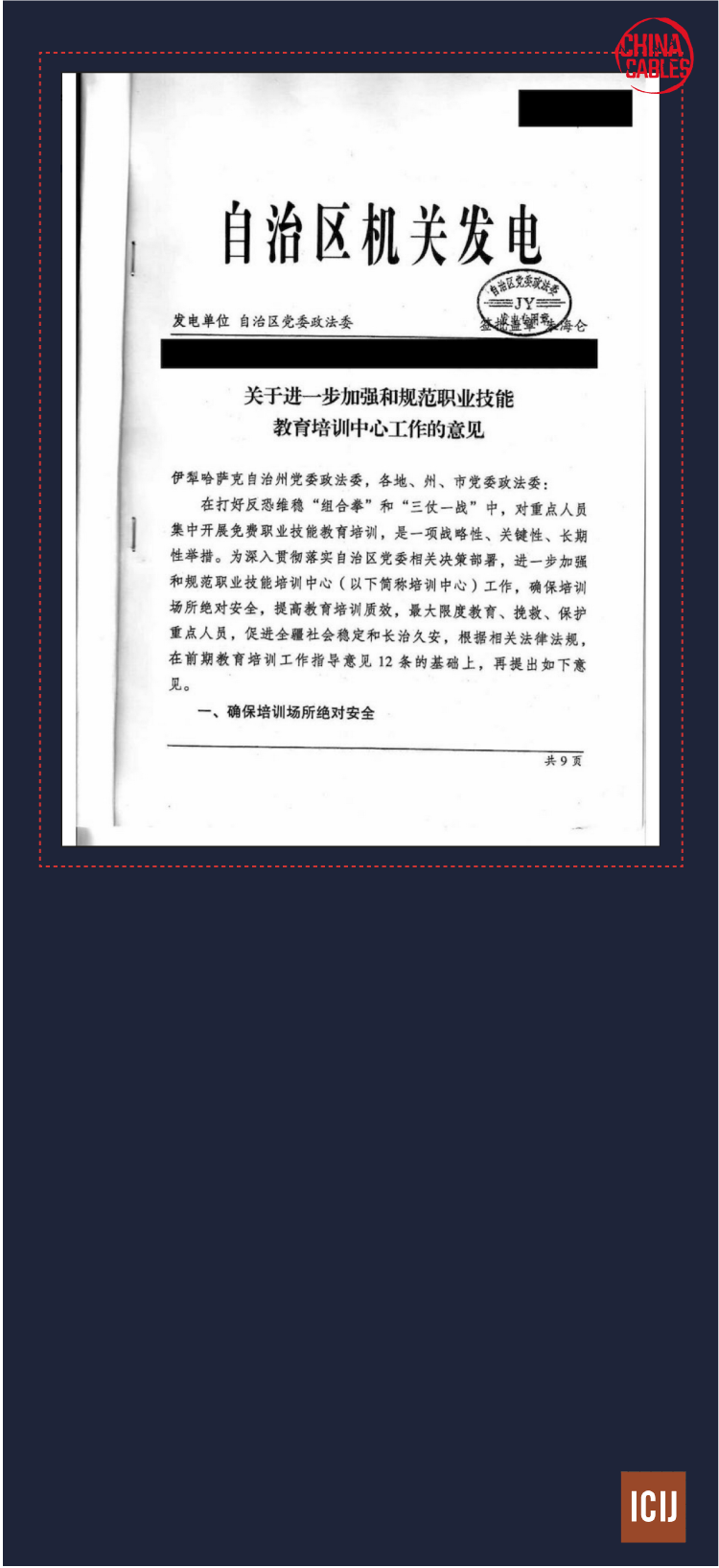

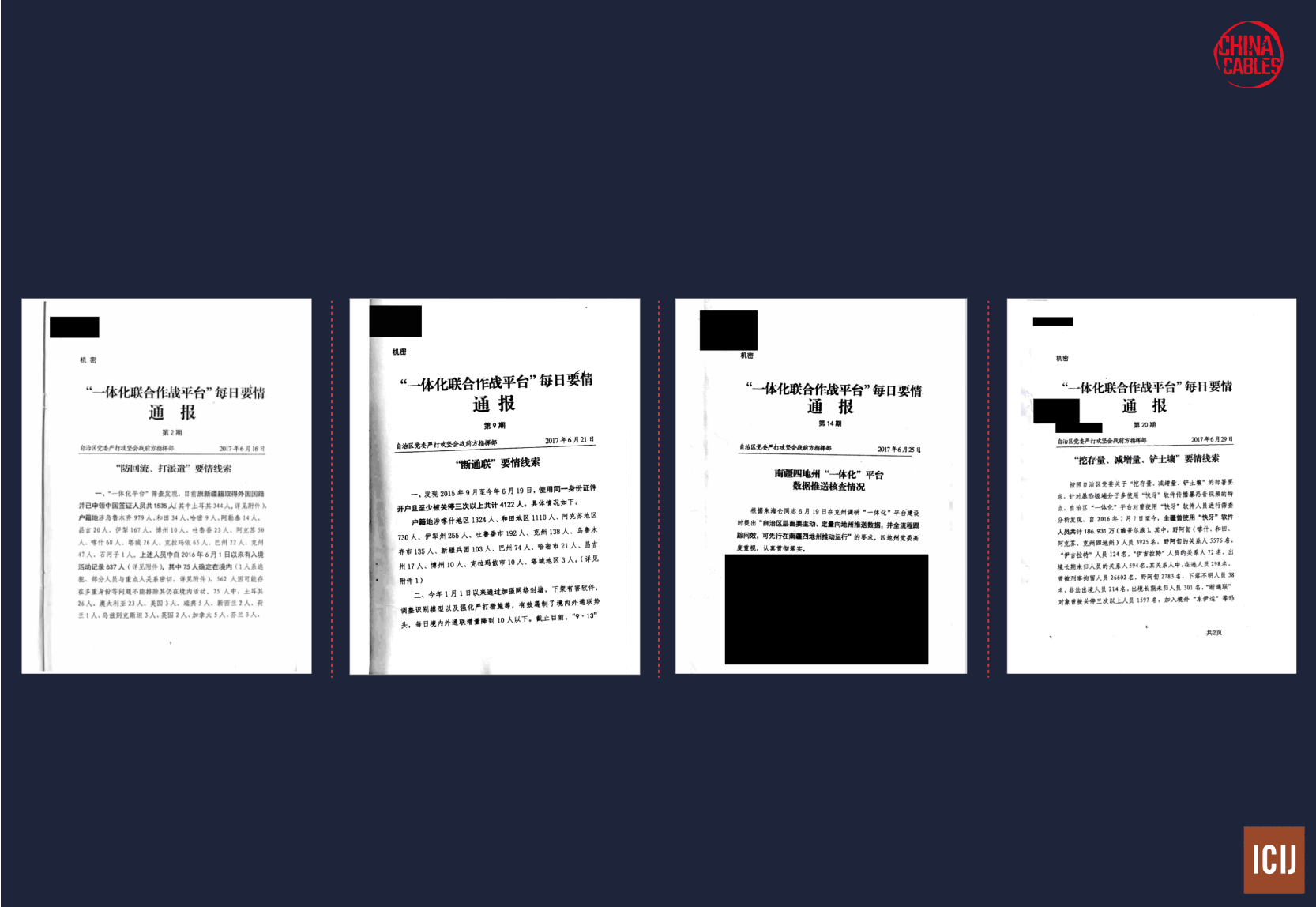

Four “bulletins”

These four “bulletins,” written in Chinese, are secret government intelligence briefings from the Integrated Joint Operation Platform, a centralized data collection system. The bulletins – for the first time – lay out the connection between mass surveillance and the Xinjiang camps.

Bulletin #2

Bulletin #9

Bulletin #14

Bulletin #20

Four “bulletins”

These four “bulletins,” written in Chinese, are secret government intelligence briefings from the Integrated Joint Operation Platform, a centralized data collection system. The bulletins – for the first time – lay out the connection between mass surveillance and the Xinjiang camps.

Bulletin #2

Bulletin #9

Bulletin #14

Bulletin #20

Four “bulletins”

These four “bulletins,” written in Chinese, are secret government intelligence briefings from the Integrated Joint Operation Platform, a centralized data collection system. The bulletins – for the first time – lay out the connection between mass surveillance and the Xinjiang camps.

Bulletin #2

Bulletin #9

Bulletin #14

Bulletin #20

Four “bulletins”

These four “bulletins,” written in Chinese, are secret government intelligence briefings from the Integrated Joint Operation Platform, a centralized data collection system. The bulletins – for the first time – lay out the connection between mass surveillance and the Xinjiang camps.

Bulletin #2

Bulletin #9

Bulletin #14

Bulletin #20

How did ICIJ obtain the China Cables?

The secret documents came to ICIJ via a chain of exiled Uighurs.

What is new in China Cables?

The China Cables investigation provides authoritative confirmation, in the Chinese government’s own documents and words, of the operational plans underpinning the internment centers in Xinjiang and the mechanics of the region’s Orwellian mass surveillance and “predictive policing” system.

The documents provide a wealth of detail on the comprehensive system of social control within the camps, including strict measures to prevent escape, that bely official claims that they are humane educational facilities.

The documents also reveal the workings of a Chinese program to monitor citizens and collect information in a database called the Integrated Joint Operations Platform. They show that Chinese police are making mass arrests based on orders from this massive data collection and analysis system that uses artificial intelligence to select huge swaths of the Xinjiang community as candidates for detention.

The bulletins for the first time reveal that authorities flag citizens as suspicious solely for using a popular communications app known as Zapya. The app allows users to share content offline and authorities deemed that it could be used to spread materials with “violent terroristic characteristics.” According to one of the leaked bulletins, as of June 2017, more than 1.8 million Uighurs in Xinjiang were using Zapya.

News organizations have previously reported that camp inmate populations included some foreign nationals. Now the bulletins show that their presence in the camps was not accidental but rather an explicit policy objective. The bulletins also provide official confirmation that thousands of others are targeted solely for having traveled abroad. People who fall under suspicion may be detained without judicial orders or trials.