Ten detainees wearing blue and yellow prison smocks sit in a basement cell, staring up at a TV that shows a speech by a local Xinjiang government official. Blue-clad guards, one holding a club about as big as a baseball bat, stand nearby.

Beneath Chinese flags, several officials stroll along a brightly lit detention center corridor, like visitors at a zoo, peering down through grates into basement cells whose inhabitants are out of view.

A third photograph shows what appears to be an interrogation. A young man, hands and feet shackled to what Chinese police call a “tiger chair,” faces an officer at a desk equipped with a computer, a camera and a microphone. A framed poster displaying the Chinese Communist Party’s hammer and sickle emblem leans against a wall, and a helmeted officer in full riot gear, visor down, holds a riot shield.

These photos are part of the Xinjiang Police Files, an unprecedented leak of thousands of images and documents from the public security bureaus of China’s Konasheher and Tekes counties. The two counties are in Xinjiang, the majority-Muslim region in northwestern China where the national government has held hundreds of thousands of Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities in mass-internment camps.

The leak contains the first photographs taken inside the camps and obtained by news organizations without official authorization. The photos serve as irrefutable evidence of the highly militarized nature of the camps and present a stark contrast with those, previously published, that were taken on government-organized press tours.

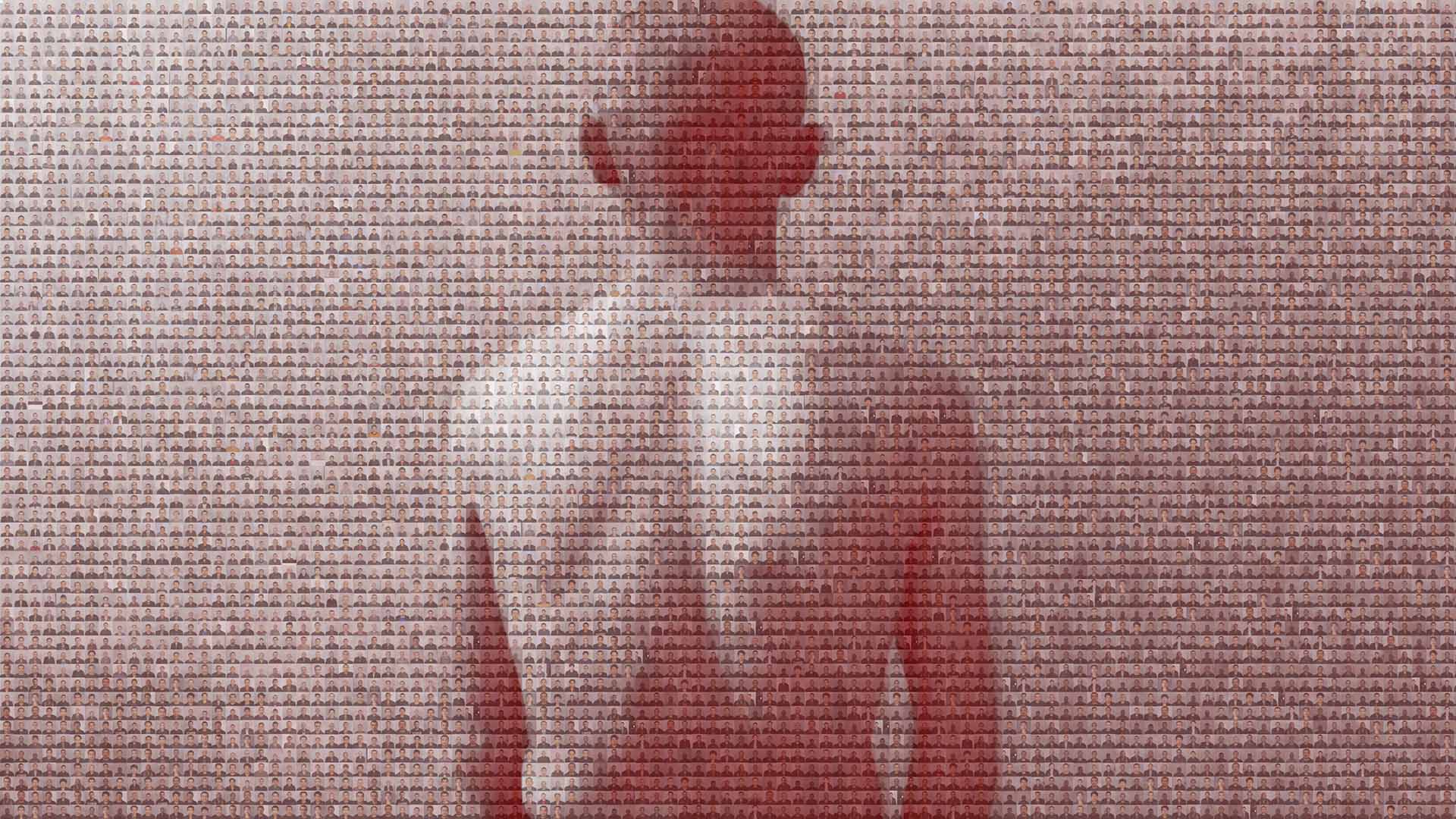

Also included are the mug shots of more than 2,800 detainees, dazed men, women and teenagers staring blankly into a camera. Xinjiang residents’ faces also occupy one column of a spreadsheet amid thousands of rows of personal data — age, profession, hometown and other personal information — in Chinese characters.

In addition to photos, the leak provides confidential government documents, including speeches by high-ranking Chinese officials outlining their plans to repress, “educate” and punish members of ethnic minority groups in Xinjiang. Among the files, too, are internal police presentations, some for training purposes, on how to search and arrest suspects, and how to use handcuffs and other equipment. One document marked “confidential” outlines surveillance measures to be put in place by Yili prefecture officers during a visit to Xinjiang by a group of European diplomats in the summer of 2018.

Taken together, the photographs and documents refute the Chinese government’s claims that the camps are merely “educational centers.”

The leaked records, most dating to 2017 or 2018, represent a major advance in public access to knowledge of China’s mass-detention policy and the implementation of that policy at the local level, in this case, the western prefectures of Kashgar and Yili.

It’s [one] thing to know it, and another thing to see it. — researcher Adrian Zenz

The Xinjiang Police Files were obtained by researcher Adrian Zenz, who shared the documents with a group of 14 news organizations, including the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists.

Zenz, a senior fellow at the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation, a Washington-based think tank, wrote a peer-reviewed academic paper based on the documents that analyzes the leaked data and compares it with publicly available information. He found, for instance, that about 23,000 people in Konasheher county, in Xinjiang’s southwestern Kashgar prefecture, or more than 12% of the adults there, were in some form of internment in 2018. The paper was published in the Journal of the European Association for Chinese Studies.

“The image material is stunning,” Zenz told ICIJ. “It’s really fortunate that this material can come out because it would blow away Chinese propaganda attempts” to whitewash what’s happening in Xinjiang.

“It’s very touching,” he added. “It’s one thing to know it, and another thing to see it.”

The leak comes as the U.N. high commissioner for human rights, Michelle Bachelet, prepares to make a long-delayed visit to Xinjiang this week.

A growing body of evidence documents the campaign of mass detention and forced assimilation in Xinjiang, begun under President Xi Jingping and his subordinates in 2017. The Chinese government has called the camps “vocational skills education and training centers,” but the Xinjiang Police Files and previous exposés by journalists, researchers and activists point to another conclusion. They reinforce allegations that the camps are part of a nationwide policy to promote conformity to Communist Party doctrine and majority Han cultural norms and crack down on expressions of cultural, political and religious diversity.

As many as 1 million Uyghurs and members of other Turkic minorities were held in the camps in 2018, according to estimates by U.N. and U.S. officials. There is no precise estimate of the number of detainees since 2017.

The Chinese government dismisses accusations of human rights violations as “fabricated lies and disinformation,” asserting that the so-called training centers are intended to improve labor skills and to alleviate poverty. The government also says that some of the measures deployed in Xinjiang are part of a campaign to combat what it calls acts of terrorism by Uyghur extremists.

“Xinjiang has taken a host of decisive, robust and effective deradicalization measures,” Liu Pengyu, a spokesperson with the Chinese embassy in Washington D.C., told ICIJ and its media partners in an email.

“The region now enjoys social stability and harmony, as well as economic development and prosperity. The local people are living a safe, happy and fulfilling life,” Liu said.

“These facts,” he added, “speak volumes about the effectiveness of China’s Xinjiang policy” and “are the most powerful response to all sorts of lies and disinformation on Xinjiang.”

Liu did not respond to the reporters’ specific questions about the Xinjiang Police Files.

The camps’ punitive function stands out in photographs and other information in the leak.

“The people in them are being treated very much as criminalized elements,” said Michael Clarke, an adjunct professor at the Australia-China Relations Institute in Sydney, who reviewed Zenz’s report and underlying documents.

In an interview with USA Today, an ICIJ media partner, Clarke said that “dribs and drabs” of visual evidence of the camps’ prison-like conditions had emerged previously. “But nothing like this,” he said.

The camps’ existence and an extrajudicial program for the mass detention of minorities in Xinjiang first emerged in satellite photos and sporadic firsthand accounts of Uyghur refugees and former detainees. Witnesses also told of widespread torture, rape and forced sterilization. In 2019, the China Cables investigation by ICIJ and 17 media partners, based on classified Chinese government documents, exposed the operations manual for Xinjiang detention camps and the region’s system of mass surveillance.

The revelations have prompted the United States, members of the European Union, and other Western nations to sanction Chinese officials and companies deemed to have enabled human rights violations in Xinjiang.

The U.S. and other governments now officially refer to Beijing’s targeting of Uyghurs and other Muslim minorities as a form of “genocide.” In 2021, the U.S. enacted a law to stop the import of goods suspected of being made using Uyghurs’ forced labor.

Beijing, in turn, has levied sanctions against Zenz and others who, the government claims, “severely harm China’s sovereignty and interests and maliciously spread lies and disinformation.”

The Xinjiang Police Files

The leaked documents were created or collected when the Chinese government’s mass-detention program was at the height of its intensity.

The data set’s 5,074 mug shots appear to be of area residents photographed by law enforcement authorities from January to July 2018, possibly as part of an effort to collect biometric data, according to Zenz’s review of timestamps accompanying the images.

About 2,900 of those in the mug shots had been detained before their pictures were taken, and their ages ranged from 15 to 73, according to Zenz’s analysis of text files. The detainees included 15 minors.

Some photos show detainees being photographed under close watch, women by female staffers in civilian clothes, men by male guards in full tactical gear.

Others are just mug shots. In one, an older man, unshaved and wearing a stained sweater, looks shyly at the camera. In another, a female staffer in glasses towers over an older woman who sits in front of a light gray background and stares blankly at the camera.

Other images in the cache show an interior space that may have been used for so-called re-education purposes in Xinjiang’s Tekes county, Zenz’s report says.

The pictures of detainees watching the televised speech by the politician and of the young man in restraints are from this batch.

Some photos present chilling images of training programs. In one, three guards in full combat gear point assault rifles at a prisoner held to the ground by eight guards taking part in an anti-escape drill.

In another, at least six guards in riot gear — helmets, visors, and clubs, and one with a shield — surround two prisoners who are shackled hands-to-feet and forced to squat with their hooded heads bent toward the floor. An officer bends over one prisoner and speaks into a walkie-talkie; another holds a camera beneath his flipped-up visor and takes a photograph.

There are photos in which small groups of male and female detainees in prison uniforms stand in a row, either singing or reciting something, as guards watch.

Ominous speeches

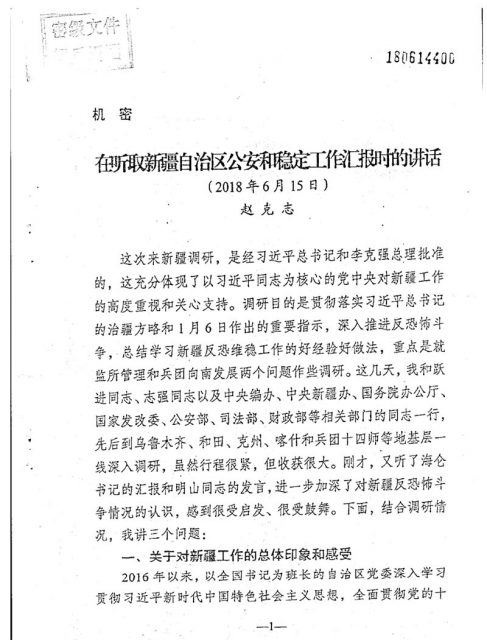

The leaked records contain new insights into the thinking of top security officials. Two documents, from June 2018, are transcripts of speeches given to a gathering of regional cadres by Zhao Kezhi, the head of China’s Ministry of Public Security, and Chen Quanguo, a member of the Politburo who is considered one of the architects of the security crackdowns in Xinjiang and Tibet.

According to the leaked transcripts, described as “classified,” Zhao and Chen outlined the government’s five-year strategy to eradicate “extremism” and bring “long-term peace” to Xinjiang.

In his remarks, Zhao indicated that in the first year, 2017, the goal was to “stabilize” the region; in the second, to “consolidate” gains and achieve “basic normalization.” The ultimate objective was “comprehensive stability” by the end of the fifth year.

Chen’s speech, echoing Zhao’s, urged officials to be on the alert, continue the fight against separatists and strengthen the security of camps and prisons. He encouraged them to shoot anyone trying to attack a detention center, an aggressive approach consistent with his advice in a previous speech that guards must fire on escapees.

“These separatist forces and two-faced people must be broken into pieces,” Chen told the cadres. “They do not know the power of our party.”

According to Zenz, “two-faced people” refers to officials who show leniency and may not always follow the government’s orders.

In 2020, the U.S. sanctioned Chen for his connection to “serious human rights abuse.”

In 2021, Beijing removed Chen from the post of Communist Party secretary of Xinjiang and replaced him with Ma Xingrui, an aerospace scientist-turned-politician who pledged to maintain the government’s hard-line policies.

Early this year, Beijing’s five-year program to eradicate “extremist forces” in Xinjiang came to an official end, according to the government. China’s foreign minister, Wang Yi, announced that the goal of bringing “stability” to the region had been achieved. The terrorism scare “is now a thing of the past,” an expert on the region told Global Times, a party newspaper.

However, experts interviewed by ICIJ and its media partners said there is little evidence that the camps have been closed.

Darren Byler, author of “Terror Capitalism”, a book about China’s mass detention of Uyghurs, said many people are still missing in Xinjiang. If they are not in the camps, Byler said, they may have been shifted to high-security detention facilities or prisons, or to factories where they are required to report for unpaid, forced labor.

“The ‘war on terror’ is ongoing,” said Byler, an anthropologist at Simon Fraser University’s campus in Vancouver, British Columbia. “And with the shift to the prisons, there’s a kind of warehousing of the people that they think are most dangerous and cannot be released.”

Mechanics of mass detention

Among the most striking documents in the leak are spreadsheets containing information on about 8,000 detainees and their internment at two vocational skills education and training centers in Konasheher county. Zenz estimates that the figure would represent nearly all those held at the two camps.

At least one of the camps, near Konasheher’s industrial zone, had cells for holding detainees in solitary confinement, a document indicates.

Another document details security procedures that officers are told to follow when transferring detainees from a camp to a “party school training center.”

According to the Student Transfer Security Plan, “students” were to be shackled and hooded, and at least two security officers were to guard each detainee. The bus convoy transporting them would be escorted to its destination by armed police.

Details from the leaked photographs and documents match accounts of former Uyghur detainees interviewed by ICIJ and other news organizations and aid groups, as well as information from public records.

In a document describing intake guidelines, for instance, authorities in Konasheher county divided detainees into 21 categories. Among them were people who allegedly posed a danger to China’s national security; those suspected of “religious extremism;” those returning from abroad or having some connection to a foreign country; and “husbands of women who are currently pregnant” in violation of China’s family-planning policy.

The Xinjiang Police Files indicate that at least 10,000 people in Konasheher county were recommended for detention or closer examination by police using a sophisticated mass-surveillance and so-called predictive-policing program known as the Integrated Joint Operations Platform, or IJOP.

A 2019 Human Rights Watch report declared that IJOP aggregates data about individuals — often without their knowledge — and flags those deemed potentially threatening or otherwise “suspicious.” According to the report, the Chinese government uses the platform to compile a massive database of intimate personal information from a range of sources. Human Rights Watch calls IJOP “China’s algorithms of repression.”

One of the leaked documents indicates that among the reasons cited for detaining people from Konasheher in 2017 and 2018 was the use of a mobile file-sharing application called Zapya, or “Kuaiya” in Chinese. The document says some Zapya users were sent to a conversion-through-education program or put in prison. Other users were placed “under review,” the document says.

ICIJ’s China Cables probe revealed that, since at least July 2016, officials closely monitored the use of the Zapya app on the phones of some Uyghurs and flagged them for further investigation. Officials suspected the app was used to exchange content of a religious or “extremist” nature.

The Xinjiang Police Files confirm the importance of IJOP to Beijing’s strategy to control the Uyghur population. In his 2018 speech, Chen told the cadres that top party officials and government ministries “continue to support Xinjiang in upgrading the national integrated platform [IJOP] for anti-terrorism and stability maintenance to a world-class level.”

Surveilling EU diplomats

Included in the Xinjiang Police Files is a four-page confidential Chinese government document, from July 2018, outlining strict security measures to be followed during a visit by a small group of European diplomats to Xinjiang.

Issued by the Yili prefecture’s public security bureau, the document orders security officers to “strictly” monitor the visitors, their contacts and “conduct at work” and to report any problems in a timely manner.

ICIJ media partner Der Spiegel, a German weekly news magazine, obtained a confidential report filed by the EU delegation to China. The undated report describes the diplomats’ “unofficial visit” to the cities of Korla, Kashgar and Hotan, which took place over five days in late June and early July 2018.

The purpose of the visit, the report says, was to understand “the human rights situation in Xinjiang” at a time when China was trying to control the narrative about the camps and the country’s broader counter-terrrorism policy.

The report criticized what it called the “heightened degree of surveillance and intrusive checks by local authorities.” It also said one of the diplomats had been stopped by police during a morning jog, taken to an army barracks and ordered to delete a photo of what the report described as “a nondescript building.”

Despite the surveillance, the report said, the diplomats were able to confirm human rights violations, including instances of racial discrimination against the Uyghur population and restrictions on its freedom of religion and thought. The report also said the diplomats were “struck” by an overwhelming presence of police, cameras and Chinese flags and the absence of Uyghur-language merchandise and public announcements.

Their report said that what China describes as its “counter-terrorism policy … will continue to be extremely problematic,” adding that “the manner in which detainees are treated will and should continue to be a preoccupation.”

U.N. human rights chief Bachelet, who is expected to visit two prefectures in Xinjiang this week, is preparing a much-anticipated report on the treatment of Muslim minorities in the region.

Clarke, the Australian scholar, said it’s very difficult to be optimistic about any easing of China’s repression of Uyghurs.

“This architecture of repression is going to be bedded down in Xinjiang for the foreseeable future,” Clarke said.

ICIJ reported this story in partnership with BBC News, Der Spiegel, USA Today, Le Monde, NHK World, YLE, Bayerischer Rundfunk, El Pais, Dagens Nyheter, Aftenposten, Mainichi Newspaper, Politiken, L’Espresso.