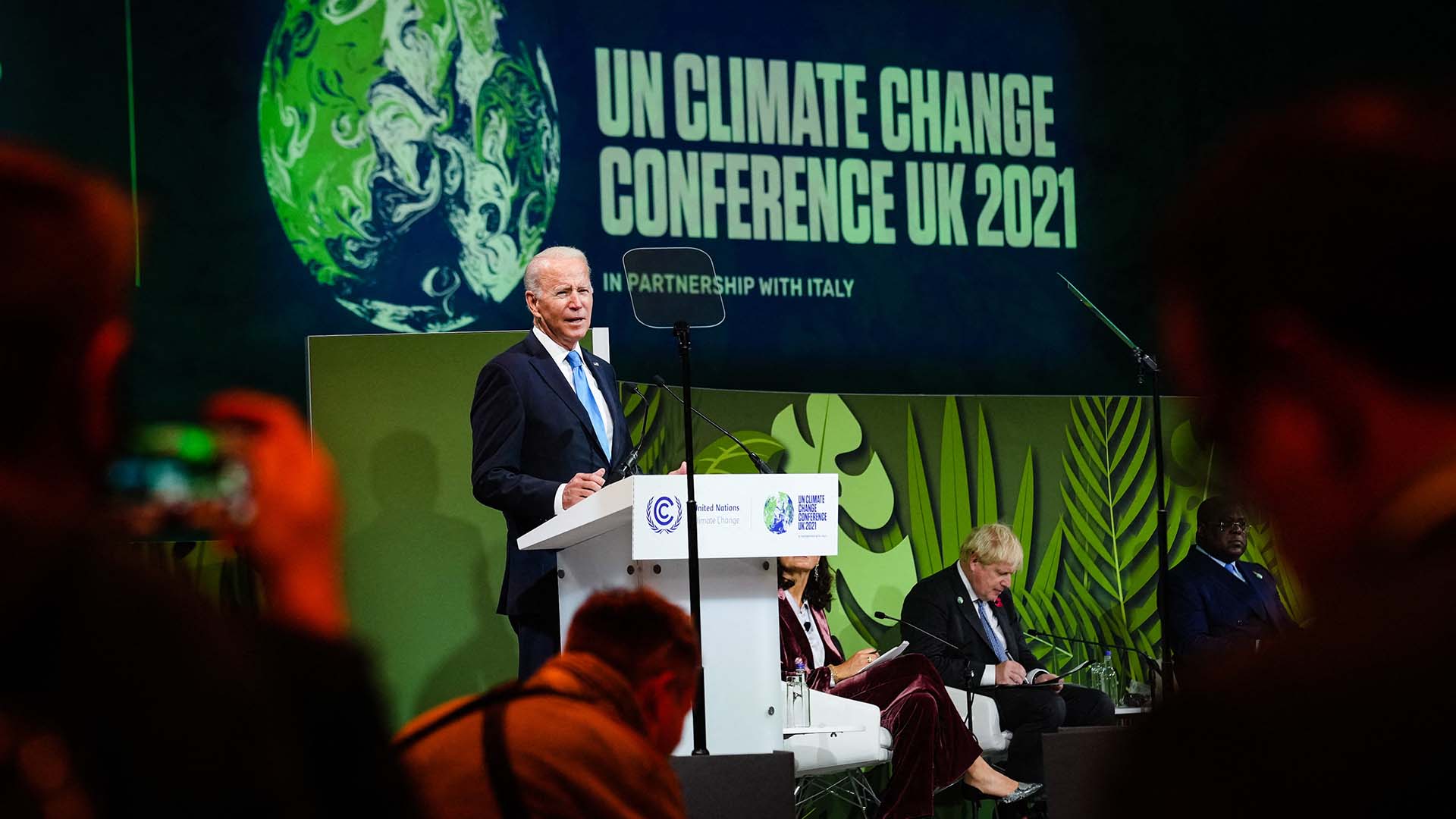

In late 2021 nearly 140 world leaders gathering at the United Nations climate talks in Glasgow pledged to end forest loss and land degradation by 2030. With the exception of notable abstainers such as India ー one of the world’s most forest-rich countries ー the politicians acknowledged crucial measures to combat the climate crisis: forest conservation, policies that promote sustainable development, and the empowerment of communities that are the stewards of forestlands worldwide.

This month, 140 reporters from 28 countries took part in Deforestation Inc., a cross-border investigation led by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. They found that some nations are falling well short of achieving those stated ambitions. According to a 2022 study by a coalition of civil society organizations under the name of Forest Declaration Assessment, “[d]espite encouraging signs, not a single global indicator is on track to meet these 2030 goals.”

New laws, old problems in Europe

As one of the world’s largest consumers of wood, palm oil and other commodities associated with forest loss, the European Union is responsible for about 10% of global forest destruction. Last year, the bloc passed a new regulation to combat deforestation. Starting from 2024, it will require every company trading, exporting or importing timber and six other commodities to check and prove that the products are not linked to harmful forest practices.

Environmental advocates and scientists agree that the new law is a step forward in the fight against climate change. Businesses operating in the bloc will have to improve their due-diligence process and verify the origin of the products they deal with, relying on new tools like geolocation technology. This means that the law can also affect the practices of companies in forest-rich countries such as Brazil, Canada, Indonesia and Cameroon, which export to Europe.

The new deforestation regulation will further require authorities in European countries to increase the number of checks on companies trading and using products linked to forest destruction.

But an ICIJ analysis of member states’ enforcement data raises questions on authorities’ ability to comply with the new requirements.

ICIJ analyzed data on the implementation of the current European timber regulation, which since 2013 bans the import and trade of wood products linked to illegal harvesting. The analysis is based on reports that member states submitted to the European Commission from 2019 to 2021. Almost half of the EU countries have not made their reports publicly available.

From 2019 to 2021, ICIJ found, officials in EU member states checked only a small fraction ー less than 1% per year ー of the estimated number of companies that imported and traded forest-products in their respective countries.

The results match findings by ICIJ and partners who investigated the trade of Myanmar teak into the European market. The reporters found that, despite 2021 sanctions on key Myanmar timber-industry players and trade restrictions recommended by European regulators since 2017, last year EU-based companies imported a total $32 million worth of timber products from Myanmar. This included teak, a precious natural resource whose trade finances the military regime. Myanmar also has one of Asia’s fastest deforestation rates.

“The implementation of the law is simply not treated with the seriousness it deserves,” said Sam Lawson, who heads Earthsight, a nonprofit environmental group. “With the EU Timber Regulation, penalties are too low, and authorities charged with enforcement are under-resourced and do not have the powers they need.”

An Earthsight investigation recently found that the loopholes in the European control system, identified by ICIJ, apply also to the trade of timber products from Belarus, an authoritarian regime and a key Russia ally. Lawson said the new deforestation regulation includes “a number of improvements aimed at making implementation and enforcement more effective,” but because it has yet to take effect, “it is not yet possible to know whether it will be more effective than its predecessor.”

In response to questions from ICIJ and its partners, a spokesperson for the European Commission acknowledged that “there is a wide variation in the coverage of operators [or companies] checked across Member States.” The spokesperson also said the Commission has “observed attempts to import timber from high-risk sources via specific Member States,” as companies “see a variation in the stringency” with which countries enforce trade rules.

India’s forest failures

India is the world’s third-biggest emitter of greenhouse gasses after China and the U.S. The Indian government did not sign the global pledge to halt forest loss and land degradation proposed at the Glasgow summit. An official told the Indian Express at the time that the government did not agree with including reference to possible reforms in countries’ trade and infrastructure development policies in the text of the declaration. But in 2021, Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced several commitments to stop and prevent land gradation in the country, including increasing India’s forest cover by more than 60 million acres by 2030.

One of the solutions touted by the government is the so-called compensatory afforestation program, a national initiative designed to compensate for forests cleared to make space for infrastructure development and industrial projects. An investigation by the Indian Express, ICIJ’s media partner in India, identified shortcomings in the program that cast doubts on the successes trumpeted by the administration and its supporters.

According to the Express’s findings, India’s definition of forest cover is so broad that it includes “all patches of land with a tree canopy density of more than 10%,” a variation from the definition accepted by the United Nations’ Food Agriculture Organization, which does not include areas predominantly under agriculture and urban land use.

Reporters with the Indian daily accessed and analyzed part of India’s forest cover data, which the government had refused to share with the media since the 1980s. They found that even roadside trees, bungalows of ministers and senior officers, the Reserve Bank of India building and parts of the campuses of the All India Institute of Medical Sciences and the Indian Institute of Technology in New Delhi are classified as “forests” in official maps.

In addition to a lack of transparency on forest-cover data collected and released by the government, the Indian Express also found that 60% of the funds allocated for the afforestation initiative ー aimed at planting trees to compensate for forest diverted for industrial activities that don’t include forest use ー remain unused. What’s more, the program focuses on developing plantations, which don’t have the same biodiversity as the natural forests and are spread out in discontinuous patches.

Reporters traveled to several sites designated as part of the afforestation program and found “barren and rocky land where new saplings are surviving precariously.” Local environmentalists have also said the government program doesn’t take into account the rights of Indigenous communities who for generations inhabited the forestlands replaced by the plantations or other projects. According to the report, “The new green tracts are a far cry from the dense forests they are meant to replace.”

Opposing forces in the U.S.

In an April 2022 executive order U.S. President Joe Biden acknowledged the “irreplaceable role” of forests in reaching net-zero greenhouse gas emissions. “We can and must take action to conserve, restore, reforest, and manage our magnificent forests here at home,” Biden wrote. He then directed the agency that administers America’s 154 national forests to conduct its first ever census of mature and old-growth stands across the country, with an eye to creating new policies to protect them. But an investigation by ICIJ partner InsideClimate News found that while the inventory is expected to be completed by the end of next month, the agency, the U.S. Forest Service, has already planned or started more than 20 logging projects on 370,000 acres of older forest around the U.S.

Climate advocates interviewed by InsideClimate News warn that logging mature forests is problematic because they store an outsized amount of carbon dioxide and are vital in the fight against global warming. They also mitigate risks of landslides in case of heavy rains.

According to research by Wild Heritage, a California-based conservation group, 76% of the 54 million acres of mature and old-growth forests that the Forest Service manages in the lower 48 states is vulnerable to logging. A Forest Service spokesperson told InsideClimate News that the information it is now gathering on old-growth is “a critical first step to informing further science questions and future management actions.” The agency added that its “top priority is to maintain and improve the health, diversity, and productivity of the nation’s forests and grasslands to meet the needs of current and future generations.”

Canada’s harmful lobbying strategy

Canada ranks third globally for old-growth forest loss, behind Russia and Brazil. The country is also home to a $34 billion forestry industry. And yet, according to an investigation by CBC News, ICIJ’s media partner, Canadian politicians have lobbied lawmakers in New York State to amend a bill aimed to prevent the state from buying products that are linked to deforestation or forest degradation. The bill, originally called New York Deforestation-Free Procurement Act, was introduced in early 2021. CBC News obtained confidential correspondence between officials from the Canadian province of Alberta and Elijah Reichlin-Melnick, a former New York state senator and co-sponsor of the bill. In a May 2022 letter sent by the Alberta premier at the time and also the province’s agriculture and forestry minister to Reichlin-Melnick, the Canadian politicians wrote that if the bill passed, it would harm the business interests of Canada’s forestry sector “and threaten jobs and supply chains of sustainably sourced products.”

The Canadian lawmakers’ efforts turned out to be successful. When it was reintroduced into the New York Senate last month, the bill was renamed the New York Tropical Deforestation-Free Procurement Act. It made no mention of boreal forests, which are typical of Canada, allowing Canadian forestry companies to export their products without further restrictions.

In California, where the California Deforestation-Free Procurement Act was introduced in early 2021, the Canadians’ playbook was similar. The California assembly passed a version of the bill mentioning the word “boreal” in April 2021. About two months later, the Canadian provincial governments of Quebec, Ontario, Alberta and British Columbia wrote to the chair of California’s Senate standing committee on governmental organization, asking to amend the bill and remove references to “boreal,” according to CBC News. The bill mentioning only “tropical forests” was eventually approved with bipartisan support but later vetoed by California governor Gavin Newsom.

Climate advocates at the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) have called the Canadian government “an antagonist to global efforts to protect our forests.” They say Canada uses its “tree planting program to hold up against its continued destruction of irreplaceable primary forests, broken forest carbon accounting system, and longstanding record of obstructionism to international efforts to protect northern forests.”

Even as it clear-cuts hundreds of thousands of hectares of boreal annually, “Canada has been positioning itself as a world leader on sustainability, and that’s really very much been a green veneer on top of what is really devastating practices on the ground,” Jennifer Skene, NRDC’s natural climate solutions policy manager, told CBC news.

Last year representatives of the Canadian government also lobbied European lawmakers to water down language in the text of the EU deforestation regulation, which was eventually approved last year. In a leaked letter to the European Commission, the Canadian ambassador asked regulators to make several amendments, including delaying references to “forest degradation” and reconsidering “burdensome traceability requirements” introduced to prevent unsustainably sourced forest products from entering the European market.

The next U.N. climate summit, or Conference of the Parties (COP) 28, is scheduled to start in November in the United Arab Emirates. The government appointed Sultan Ahmed al-Jaber, the head of the national oil company, as the president of this year’s U.N. climate conference ー a decision that sparked controversies. In a recent speech, al-Jaber urged every sector of society to be involved in the fight against climate change. “Every government, every industry, every business and every individual has a role to play,” he said at a conference in Houston, Texas. “No one can be on the sidelines.”