A massive leak of documents exposes the offshore holdings of 12 current and former world leaders and reveals how associates of Russian President Vladimir Putin secretly shuffled as much as $2 billion through banks and shadow companies.

The leak also provides details of the hidden financial dealings of 128 more politicians and public officials around the world.

The cache of 11.5 million records shows how a global industry of law firms and big banks sells financial secrecy to politicians, fraudsters and drug traffickers as well as billionaires, celebrities and sports stars.

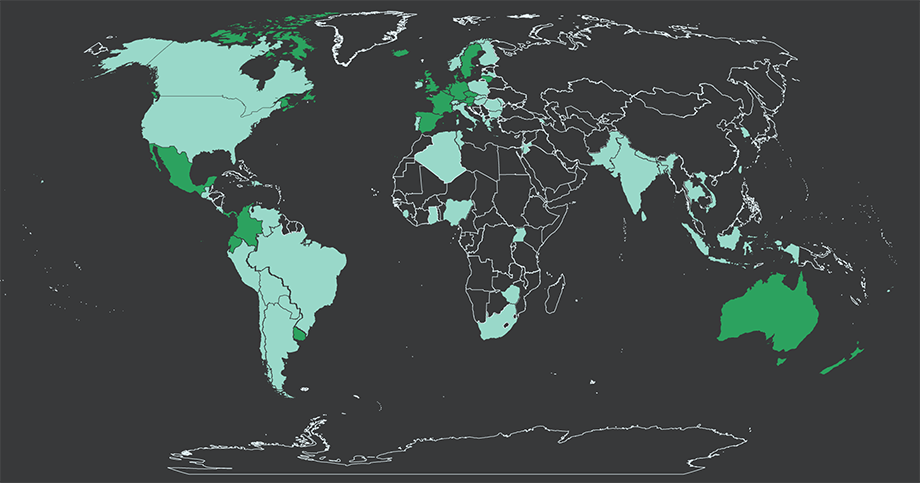

These are among the findings of a yearlong investigation by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung and more than 100 other news organizations.

The files expose offshore companies controlled by the prime minister of Iceland, the king of Saudi Arabia and the children of the president of Azerbaijan and the prime minister of Pakistan.

They also include at least 33 people and companies blacklisted by the U.S. government because of evidence that they’d been involved in wrongdoing, such as doing business with Mexican drug lords, terrorist organizations like Hezbollah or rogue nations like North Korea and Iran.

One of those companies supplied fuel for the aircraft that the Syrian government used to bomb and kill thousands of its own citizens, U.S. authorities have charged.

“These findings show how deeply ingrained harmful practices and criminality are in the offshore world,” said Gabriel Zucman, an economist at the University of California, Berkeley and author of “The Hidden Wealth of Nations: The Scourge of Tax Havens.” Zucman, who was briefed on the media partners’ investigation, said the release of the leaked documents should prompt governments to seek “concrete sanctions” against jurisdictions and institutions that peddle offshore secrecy.

World leaders who have embraced anti-corruption platforms feature in the leaked documents. The files reveal offshore companies linked to the family of China’s top leader, Xi Jinping, who has vowed to fight “armies of corruption,” as well as Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko, who has positioned himself as a reformer in a country shaken by corruption scandals. The files also contain new details of offshore dealings by the late father of British Prime Minister David Cameron, a leader in the push for tax-haven reform.

The leaked data covers nearly 40 years, from 1977 through the end of 2015. It allows a never-before-seen view inside the offshore world — providing a day-to-day, decade-by-decade look at how dark money flows through the global financial system, breeding crime and stripping national treasuries of tax revenues.

Most of the services the offshore industry provides are legal if used by the law abiding. But the documents show that banks, law firms and other offshore players have often failed to follow legal requirements that they make sure their clients are not involved in criminal enterprises, tax dodging or political corruption. In some instances, the files show, offshore middlemen have protected themselves and their clients by concealing suspect transactions or manipulating official records.

The documents make it clear that major banks are big drivers behind the creation of hard-to-trace companies in the British Virgin Islands, Panama and other offshore havens. The files list nearly 15,600 paper companies that banks set up for clients who want keep their finances under wraps, including thousands created by international giants UBS and HSBC.

The records reveal a pattern of covert maneuvers by banks, companies and people tied to Russian leader Putin. The records show offshore companies linked to this network moving money in transactions as large as $200 million at a time. Putin associates disguised payments, backdated documents and gained hidden influence within the country’s media and automotive industries, the leaked files show.

A Kremlin spokesman did not answer questions for this story, but instead went public March 28 with charges that ICIJ and its media partners were preparing a misleading “information attack” on Putin and people close to him.

The leaked records — which were reviewed by a team of more than 370 journalists from 76 countries — come from a little-known but powerful law firm based in Panama, Mossack Fonseca, that has branches in Hong Kong, Miami, Zurich and more than 35 other places around the globe.

The firm is one of the world’s top creators of shell companies, corporate structures that can be used to hide ownership of assets. The law firm’s leaked internal files contain information on 214,488 offshore entities connected to people in more than 200 countries and territories. ICIJ will release the full list of companies and people linked to them in early May.

The data includes emails, financial spreadsheets, passports and corporate records revealing the secret owners of bank accounts and companies in 21 offshore jurisdictions, from Nevada to Singapore to the British Virgin Islands.

Mossack Fonseca’s fingers are in Africa’s diamond trade, the international art market and other businesses that thrive on secrecy. The firm has serviced enough Middle East royalty to fill a palace. It’s helped two kings, Mohammed VI of Morocco and King Salman of Saudi Arabia, take to the sea on luxury yachts.

In Iceland, the leaked files show how Prime Minister Sigmundur David Gunnlaugsson and his wife secretly owned an offshore firm that held millions of dollars in Icelandic bank bonds during that country’s financial crisis.

The files include a convicted money launderer who claimed he’d arranged a $50,000 illegal campaign contribution used to pay the Watergate burglars, 29 billionaires featured in Forbes Magazine’s list of the world’s 500 richest people and movie star Jackie Chan, who has at least six companies managed through the law firm.

As with many of Mossack Fonseca’s clients, there is no evidence that Chan used his companies for improper purposes. Having an offshore company isn’t illegal. For some international business transactions, it’s a logical choice.

The Mossack Fonseca documents indicate, however, that the firm’s customers have included Ponzi schemers, drug kingpins, tax evaders and at least one jailed sex offender. A U.S. businessman convicted of traveling to Russia to have sex with underage orphans signed papers for an offshore company while he was serving his prison sentence in New Jersey, the records show.

The files contain new details about major scandals ranging from England’s most infamous gold heist to the bribery allegations convulsing FIFA, the body that rules international soccer.

The leaked documents reveal that the law firm of Juan Pedro Damiani, a member of FIFA’s ethics committee, had business relationships with three men who have been indicted in the FIFA scandal — former FIFA vice president Eugenio Figueredo and Hugo and Mariano Jinkis, the father-son team accused of paying bribes to win broadcast rights to Latin American soccer events. The records show that Damiani’s law firm in Uruguay represented an offshore company linked to the Jinkises and seven companies linked to Figueredo.

In response to the reporting by ICIJ and its media partners, FIFA’s ethics panel has launched a preliminary investigation into Damiani’s relationship to Figueredo. A spokesman for the committee said Damiani first informed the panel about his business ties to Figueredo on March 18. That was one day after the reporting team sent questions to Damiani about his law firm’s work for companies tied to the former FIFA vice president.

The world’s best soccer player, Lionel Messi, is also found in the documents. The records show Messi and his father were owners of a Panama company: Mega Star Enterprises Inc. This adds a new name to the list of shell companies known to be linked to Messi. His offshore dealings are currently the target of a tax evasion case in Spain.

Whether they’re famous or unknown, Mossack Fonseca works aggressively to protect its clients’ secrets. In Nevada, the records show, the law firm tried to shield itself and its clients from the fallout from a legal action in U.S. District Court by removing paper records from its Las Vegas branch and having its tech gurus wipe electronic records from phones and computers.

The leaked files show the firm regularly offered to backdate documents to help its clients gain advantage in their financial affairs. It was so common that in 2007 an email exchange shows firm employees talking about establishing a price structure — clients would pay $8.75 for each month farther back in time that a corporate document would be backdated.

In a written response to questions from ICIJ and its media partners, the firm said it “does not foster or promote illegal acts. Your allegations that we provide shareholders with structures supposedly designed to hide the identity of the real owners are completely unsupported and false.”

The firm added that the backdating of documents “is a well-founded and accepted practice” that is “common in our industry and its aim is not to cover up or hide unlawful acts.”

The firm said it couldn’t answer questions about specific customers because of its obligation to maintain client confidentiality.

The law firm’s co-founder, Ramón Fonseca, said in a recent interview on Panamanian television that the firm has no responsibility for what clients do with the offshore companies that the firm sells. He compared the firm to a “car factory” whose liability ends once the car is produced. Blaming Mossack Fonseca for what people do with their companies would be like blaming a carmaker “if the car was used in a robbery,” he said.

Under scrutiny

Until recently, Mossack Fonseca has largely operated in the shadows. But it has come under growing scrutiny as governments have obtained partial leaks of the firm’s files and authorities in Germany and Brazil began probing its practices.

In February 2015, Süddeutsche Zeitung reported that German law-enforcement agencies had launched a series of raids targeting one of the country’s biggest banks, Commerzbank, in a tax-fraud investigation that authorities said could lead to criminal charges against Mossack Fonseca employees.

In Brazil, the law firm has become a target in a bribery and money laundering investigation dubbed “Operation Car Wash” (“Lava Jato,” in Portuguese), which has led to criminal charges against leading politicians and an investigation of popular former president Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva. The scandal threatens to unseat current President Dilma Rousseff.

In January, Brazilian prosecutors labeled Mossack Fonseca as a “big money launderer” and announced they had filed criminal charges against five employees of the firm’s Brazilian office for their role in the scandal.

Mossack Fonseca denies any wrongdoing in Brazil.

The disclosures found inside the law firm’s leaked files dramatically expand on previous leaks of offshore records that ICIJ and its reporting partners have revealed in the past four years.

In the largest media collaboration ever undertaken, journalists working in more than 25 languages dug into Mossack Fonseca’s inner workings and traced the secret dealings of the law firm’s customers around the world. They shared information and hunted down leads generated by the leaked files using corporate filings, property records, financial disclosures, court documents and interviews with money laundering experts and law-enforcement officials.

Reporters at Süddeutsche Zeitung obtained millions of records from a confidential source and shared them with ICIJ and other media partners. The news outlets involved in the collaboration did not pay for the documents.

Before Süddeutsche Zeitung obtained the leak, German tax authorities bought a smaller set of Mossack Fonseca documents from a whistleblower, a move that triggered the raids in Germany in early 2015. This smaller set of files has since been offered to tax authorities in the United Kingdom, the United States and other countries, according to sources with knowledge of the matter.

The larger set of files obtained by the news organizations offers more than a snapshot of one law firm’s business methods or a catalog of its more unsavory customers. It allows a far-reaching view into an industry that has worked to keep its practices hidden — and offers clues as to why efforts to reform the system have faltered.

The story of Mossack Fonseca is, in many ways, the story of the offshore system itself.

Crime of the century

Before dawn on Nov. 26, 1983, six robbers slipped into the Brink’s-Mat warehouse at London’s Heathrow Airport. The thugs tied up the security guards, doused them in gasoline, lit a match and threatened to set them afire unless they opened the warehouse’s vault. Inside, the thieves found nearly 7,000 gold bars, diamonds and cash.

“Thanks ever so much for your help. Have a nice Christmas,” one of the crooks said as they departed.

British media dubbed the heist the “Crime of the Century.” Much of the loot — including the cash reaped by melting the gold and selling it — was never recovered. Where the missing money went is a mystery that continues to fascinate students of England’s underworld.

Now documents within Mossack Fonseca’s files reveal that the law firm and its co-founder, Jürgen Mossack, may have helped the conspirators keep the spoils out of the hands of authorities by protecting a company tied to Gordon Parry, a London wheeler-dealer who laundered money for the Brink’s-Mat plotters.

Sixteen months after the robbery, the records show, Mossack Fonseca set up a Panama shell company called Feberion Inc. Jürgen Mossack was one the company’s three “nominee” directors, a term used in the business for stand-ins who control a company on paper but exercise no real authority over its activities.

An internal memo written by Mossack shows he was aware in 1986 that the company was “apparently involved in the management of money from the famous theft from Brink’s-Mat in London. The company itself has not been used illegally, but it could be that the company invested money through bank accounts and properties that was illegitimately sourced.”

Mossack Fonseca records from 1987 make it clear that Parry was behind Feberion. Rather than help authorities gain access to Feberion’s assets, the law firm took steps that prevented U.K. police from gaining control of the company, the records show.

After police obtained the two certificates that controlled the company’s ownership, Mossack Fonseca arranged for Feberion to issue 98 new shares, a move that appears to have effectively wrested control away from investigators, the leaked records show.

It was not until 1995 — three years after Parry was sent to prison for his role in the gold caper — that Mossack Fonseca ended its business relationship with Feberion.

A spokesman for the law firm said any allegations the firm helped shield the proceeds of the Brink’s-Mat robbery “are entirely false.” The spokesman said Jürgen Mossack “never had any dealings” with Parry and was never contacted by police about the case.

Mossack Fonseca’s defense of the dodgy company illustrates how far many offshore operatives will go to serve their customers’ interests.

The offshore system relies on a sprawling global industry of bankers, lawyers, accountants and go-betweens who work together to protect their clients’ secrets. These secrecy experts use anonymous companies, trusts and other paper entities to create complex structures that can be used to disguise the origins of dirty money.

“They are the gasoline that runs the engine,” says Robert Mazur, a former U.S. drug agent and author of The Infiltrator: My Secret Life Inside the Dirty Banks Behind Pablo Escobar’s Medellín Cartel. “They’re an extraordinarily important piece of the formula of success for criminal organizations.”

Mossack Fonseca told ICIJ that it follows “both the letter and spirit of the law. Because we do, we have not once in nearly 40 years of operation been charged with criminal wrongdoing.”

The men who founded the firm decades ago — and continue today as its main partners — are well-known figures in Panamanian society and politics.

Jürgen Mossack is a German immigrant whose father sought a new life in Panama for his family after serving in Hitler’s Waffen-SS during World War II. Ramón Fonseca is an award-winning novelist who has worked in recent years as an adviser to Panama’s president. He took a leave of absence as presidential adviser in March after his firm was implicated in the Brazil scandal and ICIJ and its partners began to ask questions about the law firm’s practices.

From its base in Panama, one of the world’s top financial secrecy zones, Mossack Fonseca seeds anonymous companies in Panama, the British Virgin Islands and other financial havens.

The law firm has worked closely with big banks and big law firms in places like The Netherlands, Mexico, the United States and Switzerland, helping clients move money or slash their tax bills, the secret records show.

An ICIJ analysis of the leaked files found that more than 500 banks, their subsidiaries and branches have worked with Mossack Fonseca since the 1970s to help clients manage offshore companies. UBS set up more than 1,100 offshore companies through Mossack Fonseca. HSBC and its affiliates created more than 2,300.

In all, the files indicate Mossack Fonseca worked with more than 14,000 banks, law firms, company incorporators and other middlemen to set up companies, foundations and trusts for customers, the records show.

Mossack Fonseca says these middlemen are its true clients, not the eventual customers who use offshore companies. The firm says these middlemen provide additional layers of oversight for reviewing new customers. As for its own procedures, Mossack Fonseca says they often exceed “the existing rules and standards to which we and others are bound.”

In its efforts to protect Feberion Inc., the shell company linked to the Brink’s-Mat gold heist, Mossack Fonseca used the services of a Panama-based firm, Chartered Management Company, run by Gilbert R.J. Straub, an American expatriate who played a cameo role in the Watergate scandal.

In 1987, as U.K. police were investigating the shell company, Jürgen Mossack and Feberion’s other paper directors resigned, with the understanding they’d be replaced by new directors appointed by Straub’s Chartered Management, the secret files show.

Straub was eventually caught in a U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration sting that was unrelated to the Brink’s-Mat case, according to Mazur, the former undercover agent. During one of his deep-cover stints, Mazur built the case that led Straub to plead guilty to money laundering in 1995. Believing Mazur was a well-connected money launderer, Straub tried to establish his own criminal bona fides, Mazur says, by describing how he’d illegally channeled cash to President Nixon’s 1972 re-election campaign.

Secrets and victims

Nick Kgopa’s father died when Nick was 14. His father’s workmates at a gold mine in northern South Africa said Nick’s dad had been killed by chemical exposure.

Nick and his mother and his younger brother, who is deaf, survived thanks to monthly checks from a fund for widows and orphans of mineworkers.

One day the payments stopped.

His family was one of many that lost out because of a $60 million investment fraud pulled off by South African businessmen. Prosecutors alleged that a group of individuals connected to an asset management company, Fidentia, had schemed to loot millions from investment funds — including the mineworkers’ death benefits pool that was supporting some 46,000 widows and orphans.

Mossack Fonseca’s leaked documents show that at least two of the men involved in the fraud used the Panama-based law firm to create offshore companies — and that Mossack Fonseca was willing to help one of the fraudsters protect his money even after authorities publicly linked him to the scandal.

Ponzi schemers and other fraudsters who bilk large numbers of victims often use offshore structures to pull of their schemes or hide the proceeds. The Fidentia case isn’t the only big-ticket fraud that appears in the files of Mossack Fonseca’s clients.

In Indonesia, for example, small investors claim a company incorporated by Mossack Fonseca in the British Virgin Islands was used to scam 3,500 people out of at least $150 million.

“We really need that money for our son’s education fee this April,” one Indonesian investor emailed Mossack Fonseca in April 2007 after payouts had stopped.

“You can give us any suggestion something we can do,” the investor asked in broken English after seeing Mossack Fonseca’s name on the investment fund’s advertising leaflet.

In the Fidentia case, Mossack Fonseca’s records show that one of the men later jailed in South Africa for his role in the fraud, Graham Maddock, paid Mossack Fonseca $59,000 in 2005 and 2006 to create two sets of offshore companies, including one called Fidentia North America. The law firm’s records say it gave him “the VIP service.”

Mossack Fonseca also created offshore structures for Steven Goodwin, a man that prosecutors later claimed had played an “instrumental role” within the Fidentia swindle. As the scandal broke in 2007, Goodwin flew to Australia, then to the U.S., where a Mossack Fonseca lawyer met with him at a luxury hotel in Manhattan to discuss his offshore holdings, the firm’s internal records show.

The firm official later wrote that he and Goodwin “spoke deeply” about the Fidentia scandal and that he had “convinced Goodwin to better protect” his offshore company’s assets by passing them to a third party.

In his memo, the firm official told colleagues that Goodwin wasn’t involved in the scandal “in any way whatsoever” — he was just “a victim of the circumstances.”

In April 2008, the FBI arrested Goodwin in Los Angeles and sent him back to South Africa, where he pleaded guilty to fraud and money laundering. He was sentenced to 10 years in prison.

A month after Goodwin’s sentencing, an employee at Mossack Fonseca suggested a plan for frustrating South African prosecutors who were expected to start digging into assets linked to Goodwin’s offshore company, Hamlyn Property LLP, which had been set up to buy real estate in South Africa.

The employee proposed having an accountant “prepare” audits for 2006 and 2007 “to try to prevent the prosecutor from taking actions against the entities behind Hamlyn.” He set off “prepare” in quote marks in his email.

It’s unclear whether the proposal was adopted.

Mossack Fonseca did not answer questions from ICIJ about its relationship with Goodwin. A representative for Goodwin told ICIJ that Goodwin “had nothing whatsoever” to do Fidentia’s collapse “or anything directly or indirectly to do with the 46,000 widows and orphans.”

Politically exposed

On Feb. 10, 2011, an anonymous company in the British Virgin Islands named Sandalwood Continental Ltd. loaned $200 million to an equally shadowy firm based in Cyprus called Horwich Trading Ltd.

The following day, Sandalwood assigned the rights to collect payments on the loan — including interest — to Ove Financial Corp., a mysterious company in the British Virgin Islands.

For those rights, Ove paid $1.

But the money trail didn’t end there.

The same day, Ove reassigned its rights to collect on the loan to a Panama company called International Media Overseas.

It too paid $1.

In the space of 24 hours the loan had, on paper, traversed three countries, two banks and four companies, making the money all but untraceable in the process.

There were plenty of reasons why the men behind the transaction might want it disguised, not least of all because the money trail came uncomfortably close to Russian leader Vladimir Putin.

St. Petersburg-based Bank Rossiya, an institution whose majority owner and chairman has been called one of Putin’s “cashiers,” established Sandalwood Continental and directed the money flow.

International Media Overseas, where rights to the interest payments from the $200 million appear to have landed, was controlled, on paper, by one of Putin’s oldest friends, Sergey Roldugin, a classical cellist who is godfather to Putin’s eldest daughter.

The $200 million loan was one of dozens of transactions totaling at least $2 billion found in the Mossack Fonseca files involving people or companies linked to Putin. They formed part of a Bank Rossiya enterprise that gained indirect influence over a major shareholder in Russia’s biggest truck maker and amassed secret stakes in a key Russian media property.

Suspicious payments made by Putin’s cronies may have in some cases been designed as payoffs, possibly in exchange for Russian government aid or contracts. The secret documents suggest that much of the loan money originally came from a bank in Cyprus that at the time was majority owned by the Russian state-controlled VTB Bank.

In a media conference call last week, Putin spokesman Dmitry Peskov said the government wouldn’t reply to “honey-worded queries” from ICIJ or its reporting partners, because they contain questions that “have been asked hundreds of times and answered hundreds of times.”

Peskov added that Russia has “available the full arsenal of legal means in the national and international arena to protect the honor and dignity of our president.”

Under national laws and international agreements, firms like Mossack Fonseca that help create companies and bank accounts are supposed to be on the lookout for clients who may be involved in money laundering, tax evasion or other wrongdoing. They are required to pay special attention to “politically exposed persons” — government officials or their family members or associates. If someone is a “PEP,” the middlemen creating their companies are expected to review their activities carefully to make sure they are not engaging in corruption.

Mossack Fonseca told ICIJ that it has “duly established policies and procedures to identify and handle those cases where individuals” qualify as PEPs.

Often, Mossack Fonseca appeared not to realize who its customers were. A 2015 internal audit found that the law firm knew the identities of the real owners of just 204 of 14,086 companies it had incorporated in Seychelles, a tax haven in the Indian Ocean.

British Virgin Islands authorities fined Mossack Fonseca $37,500 for violating anti-money-laundering rules because the firm incorporated a company for the son of former Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak but failed to identify the connection, even after the father and son were charged with corruption in Egypt. An internal review by the law firm concluded, “our risk assessment formula is seriously flawed.”

In all, an ICIJ analysis of the Mossack Fonseca files identified 61 family members and associates of prime ministers, presidents or kings.

The records show, for example, that the family of Azerbaijan President Ilham Aliyev used foundations and companies in Panama to hold secret stakes in gold mines and London real estate. The children of Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif also owned London real estate through companies created by Mossack Fonseca, the law firm’s records show.

Family members of at least eight current or former members of China’s Politburo Standing Committee, the country’s main ruling body, have offshore companies arranged though Mossack Fonseca. They include President Xi’s brother-in-law, who set up two British Virgin Islands companies in 2009.

Representatives for the Azeri, Pakistani and Chinese leaders did not respond to requests for comment.

The list of world leaders who used Mossack Fonseca to set up offshore entities includes the current president of Argentina, Mauricio Macri, who was director and vice president of a Bahamas company managed by Mossack Fonseca when he was a businessman and the mayor of Argentina’s capital, Buenos Aires. A spokesman for Macri said the president never personally owned shares in the firm, which was part of his family’s business.

During the bloodiest days of Russia’s 2014 invasion of the Ukraine’s Donbas region, the documents show, representatives of Ukrainian leader Petro Poroshenko scrambled to find a copy of a home utility bill for him to complete the paperwork to create a holding company in the British Virgin Islands.

A spokesperson for Poroshenko said the creation of the company had nothing to do with “any political and military events in Ukraine.” Poroshenko’s financial advisers said the president didn’t include the BVI firm in his 2014 financial disclosures because neither the holding company nor two related companies in Cyprus and the Netherlands have any assets. They said that the companies were part of a corporate restructuring to help sell Poroshenko’s confectionery business.

When Sigmundur David Gunnlaugsson became Iceland’s prime minister in 2013 he concealed a secret that could have damaged his political career. He and his wife shared ownership in an offshore company in the British Virgin Islands when he entered parliament in 2009. He sold his stake in the company months later to his wife for $1.

The company held bonds originally worth millions of dollars in three giant Icelandic banks that failed during the 2008 global financial crash, making it a creditor in their bankruptcies. Gunnlaugsson’s government negotiated a deal with creditors last year without disclosing his family’s financial stake in the outcome.

Gunnlaugsson has denied in recent days that his family’s financial interests influenced his stances. The leaked records do not make it clear whether Gunnlaugsson’s political positions benefited or hurt the value of the bonds held through the offshore company.

In an interview with an ICIJ media partners, Reykjavik Media and SVT, Gunnlaugsson denied hiding assets. When he was confronted with the name of the offshore company linked to him — Wintris Inc. — the prime minister said “I’m starting to feel a bit strange about these questions because it’s like you are accusing me of something.”

In an interview with an ICIJ media partners, Reykjavik Media and SVT, Gunnlaugsson denied hiding assets. When he was confronted with the name of the offshore company linked to him — Wintris Inc. — the prime minister said “I’m starting to feel a bit strange about these questions because it’s like you are accusing me of something.”

Soon after, he ended the interview.

Four days later, his wife took the matter public, posting a note on Facebook asserting that the company was hers, not his, and that she had paid all taxes on it.

Since then, members of Iceland’s parliament have questioned why Gunnlaugsson never disclosed the offshore company, with one lawmaker calling for the prime minister and his government to resign.

The prime minister has fought back, putting out an eight-page statement arguing he wasn’t required to publicly report his connection to Wintris because it was really owned by his wife and because it was “merely a holding company, not a company engaged in commercial activities.”

Offshore cover-ups

In 2005, a tour boat called the Ethan Allen sank in New York’s Lake George, drowning 20 elderly tourists. After the survivors and families of the dead sued, they learned the tour company had no insurance because fraudsters had sold it a fake policy.

Malchus Irvin Boncamper, an accountant on the Caribbean island of St. Kitts, pleaded guilty in a U.S. court in 2011 to helping the con artists launder proceeds of their frauds.

This created a problem for Mossack Fonseca, because Boncamper had served as the front man — a “nominee” director — for 30 companies created by the law firm.

Once it learned of Boncamper’s criminal conviction, Mossack Fonseca took quick action. It told its offices to replace Boncamper as director of the companies — and to backdate the records in a way that made it appear the changes had taken place, in some cases, a decade earlier.

The Boncamper case is one of the examples in the leaked files showing the law firm using questionable tactics to hide its own methods or its customers’ activities from legal authorities.

In the “Operation Car Wash” case in Brazil, prosecutors allege that Mossack Fonseca employees destroyed and hid documents to mask the law firm’s involvement in money laundering. A police document says that, in one instance, an employee of the firm’s Brazil branch sent an email instructing co-workers to hide records involving a client who may have been the target of a police investigation: “Do not leave anything. I will save them in my car or at my house.”

In Nevada, the leaked files show, Mossack Fonseca employees worked in late 2014 to obscure the links between the law firm’s Las Vegas branch and its headquarters in Panama in anticipation of a U.S. court order requiring it to turn over information on 123 companies incorporated by the law firm. Argentine prosecutors had linked those Nevada-based companies to a corruption scandal involving an associate of former presidents Néstor Kirchner and Cristina Fernández de Kirchner.

In an effort to free itself from the American court’s jurisdiction, Mossack Fonseca claimed that its Las Vegas office, MF Nevada, wasn’t in fact a branch office at all. It said it had no control over the office.

The firm’s internal records show the opposite. They indicate that the firm controlled MF Nevada’s bank account and the firm’s co-founders and another Mossack Fonseca official owned 100 percent of MF Nevada.

To erase evidence of the connection, the law firm arranged to remove paper documents from the branch and worked to delete computer traces of the link between the Nevada and the Panama operations, internal emails show. One big worry, an internal email said, was that the branch’s manager might be too “nervous” to carry out the effort, making it easy for investigators to discover “that we are hiding something.”

Mossack Fonseca declined to answer questions about the Brazil and Nevada affairs, but denied generally that it had obstructed investigations or covered up improper activities.

“It is not our policy to hide or destroy documentation that may be of use in any ongoing investigation or proceeding,” the firm said.

Reforming the secret world

In 2013, U.K. leader David Cameron urged his country’s overseas territories — including the British Virgin Islands — to work with him to “get our own houses in order” and join the fight against tax evasion and offshore secrecy.

He could have looked no further than his late father to see how challenging that would be.

Ian Cameron, a stockbroker and multimillionaire, was a Mossack Fonseca client who used the law firm to shield his investment fund, Blairmore Holdings, Inc., from U.K. taxes.

The fund’s name came from Blairmore House, his family’s ancestral country estate. Mossack Fonseca registered the investment fund in Panama even though many of its key investors were British. Ian Cameron controlled the fund from its birth in 1982 until his death in 2010.

A prospectus for investors said the fund “should be managed and conducted so that it does not become resident in the United Kingdom for United Kingdom taxation purposes.”

The fund did this by using untraceable certificates of ownership known as “bearer shares” and by employing “nominee” company officers based in the Bahamas, the law firm’s leaked records show.

Ian Cameron’s tax-haven history is an example of how deeply offshore secrecy is woven into the lives of political and financial elites around the world. It’s also an important economic engine for many countries. The weight of that self-interest has made reform difficult.

In the U.S., for example, states like Delaware and Nevada, which have allowed company owners to remain anonymous, continue to fight against efforts to require greater corporate transparency.

Mossack Fonseca’s home country, Panama, has refused to embrace a plan for worldwide exchange of information about bank accounts — out of concern that its offshore industry could be left at a competitive disadvantage. Panama officials say they will exchange information, but on a more modest scale.

The challenge that reformers and law enforcers face is how to find and stop criminal behavior when it’s buried beneath layers of secrecy. The most effective tool for breaking through this secrecy has been leaks of offshore documents that have dragged hidden dealings into the open.

Document leaks uncovered by ICIJ and its media partners have prompted legislation and official investigations in dozens of countries — and fanned fears among offshore customers who worry their secrets will be revealed.

In April 2013, after ICIJ released its “Offshore Leaks” stories based on confidential documents from the British Virgin Islands and Singapore, some Mossack Fonseca customers emailed the firm looking for reassurance that their offshore holdings were safe from scrutiny.

Mossack Fonseca told customers not to worry. It said its commitment to its clients’ privacy “has always been paramount, and in this regard your confidential information is stored in our state-of-the-art data center, and any communication within our global network is handled through an encryption algorithm that complies with the highest world-class standards.”

This story was reported and written by Bastian Obermayer , Gerard Ryle, Marina Walker Guevara, Michael Hudson, Jake Bernstein, Will Fitzgibbon, Mar Cabra, Martha M. Hamilton, Frederik Obermaier, Ryan Chittum, Emilia Diaz-Struck, Rigoberto Carvajal, Cécile Schilis-Gallego, Marcos Garcia Rey, Delphine Reuter, Matthew Caruana Galizia, Hamish Boland-Rudder, Miguel Fiandor and Mago Torres.

—

Clarification: Due to an editing error, a sentence in an earlier version of this story implied that the prime minister of Pakistan controlled an offshore company that appeared in the Panama Papers files. It is his children who control the offshore companies.