As the Czech Republic’s national elections approached in October, Andrej Babis seemed on track to win another term as the country’s prime minister. Polls showed his centrist party, ANO, leading all opponents.

Then on Oct. 3, one week before the first vote, the Pandora Papers investigation revealed that Babis — a populist who has thundered against the corruption of political and economic elites — used shell companies in tax havens to buy a chateau on the French Riviera. He did not disclose the chateau or companies, as required by Czech law. One media poll suggested 8% of his party’s supporters switched their votes as a result of the disclosures by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and its media partners.

When the votes were tallied, Babis and his party finished second, allowing a coalition of other parties to form a new government.

The fall of the Czech billionaire leader is just one of the headline-making results of the Pandora Papers investigation, the largest journalism partnership in history, which drew on the largest leak ever of confidential offshore financial documents.

In the weeks since the release of hundreds of investigative stories by more than 600 journalists from ICIJ and 150 media partners, new developments have come fast and furious.

Country leaders and other politicians scrambled to hold on to their jobs.

Governments around the globe promised tougher laws, convened public hearings and launched investigations — at least 19 probes and inquiries by the European Parliament, Europol and authorities in 15 countries.

Media outlets, anti-corruption experts and protesters clamored for aggressive efforts to end the system of offshore secrecy that allows the rich and powerful to hide money, make secret deals and evade taxes.

The New York Times headlined the media partners’ investigations as “A Money Bomb With Political Ripples.” The digital news outlet Middle East Eye called it a “financial earthquake.”

“The Pandora Papers are a wake-up call to all who care about the future of democracy,” U.S. Sen. Ben Cardin, a Maryland Democrat, said four days after the first stories in the investigation rolled out. “Thirty years after the end of the Cold War, it is time for democracies to band together and demand an end to the unprecedented corruption that has come to be the defining feature of the global order. We must purge the dirty money from our systems and deny kleptocrats safe haven.”

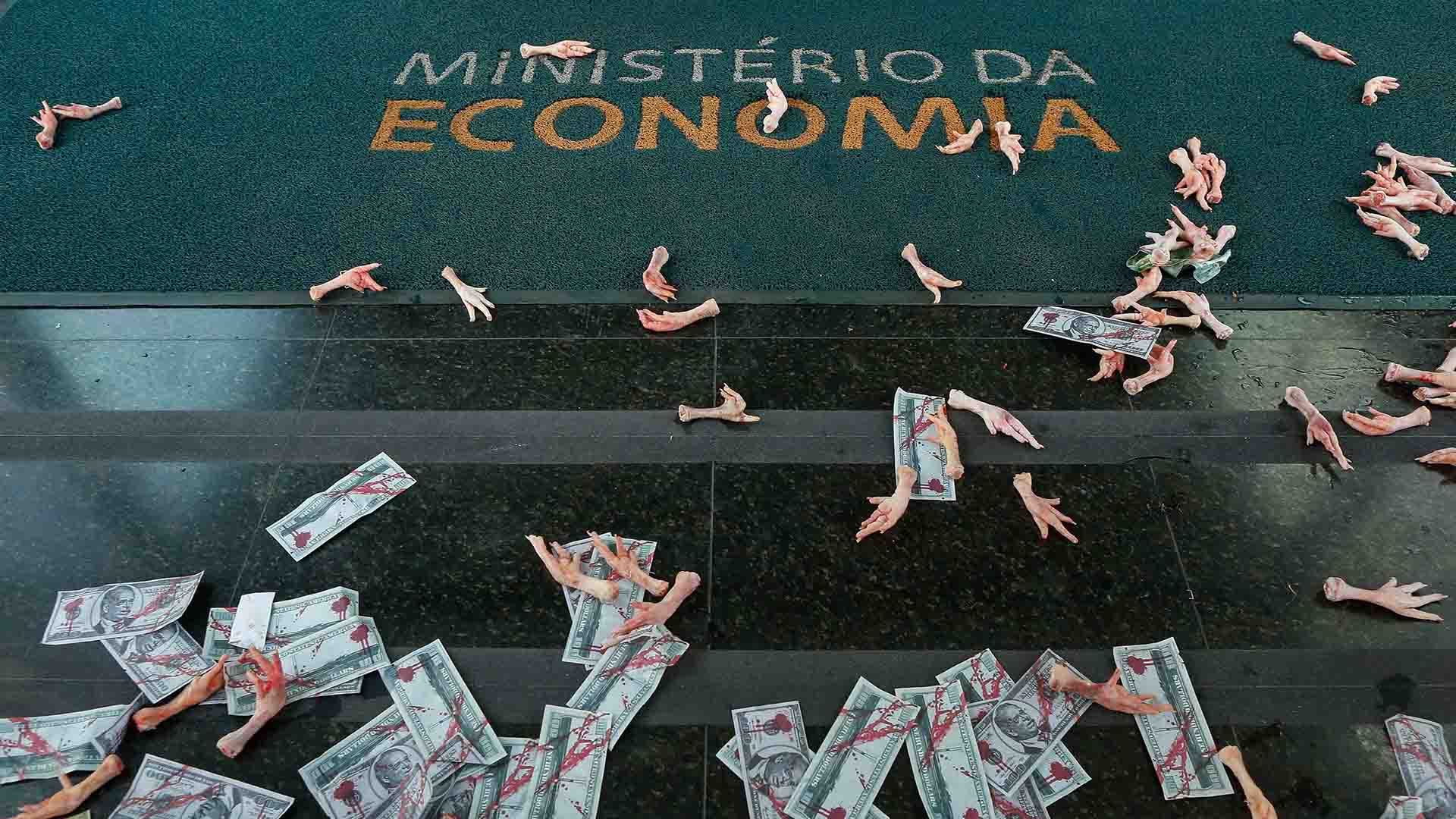

Blood and dollars

In some countries, the Pandora Papers prompted denials and pushback from high-level officials, business people and shadowy operatives.

“My name, first and foremost, is not there,” Kenyan President, Uhuru Kenyatta, said at the United Nations in New York days after the Pandora Papers investigation revealed that his name appeared on a secretive trust document from Panama.

In November, a report by the Mozilla Foundation flagged a well-coordinated online disinformation that sought to discredit findings that Kenyatta and his family owned an offshore empire.

Suspicious Twitter and Facebook accounts, including those mimicking accounts of celebrities, posted hashtags such as #phonyleaks in an effort to muddy the issue, according to the report, which was titled “How to Manipulate Twitter and Influence People: Propaganda and the Pandora Papers in Kenya.”

In Jordan, the country’s intelligence service censored Pandora Papers journalists’ reporting on King Abdullah II’s expansive and secretive property empire.

In some countries, the Pandora Papers’ disclosures sparked protests in the streets — and passionate media commentaries — about the failure of governments to fight corruption and dam the flow of dirty money.

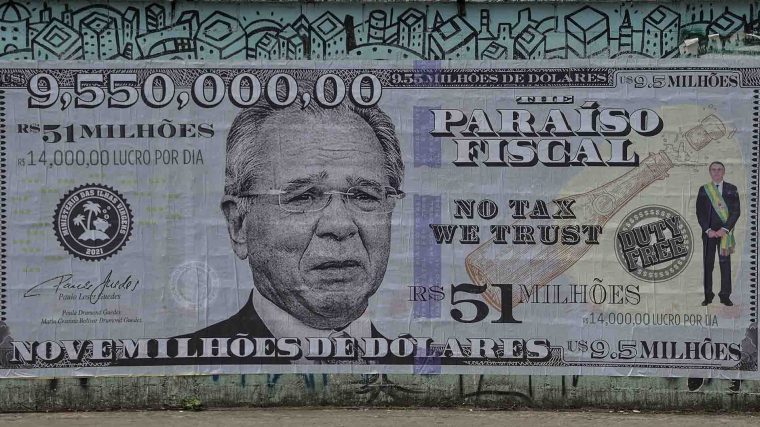

In Brazil, protestors threw red paint-spattered fake U.S. currency and real chicken feet at the office of Economy Minister Paulo Guedes after revelations he created a shell company in the British Virgin Islands. Brazil’s lower legislative chamber later summoned Guedes to explain his offshore activity.

In Cyprus, hundreds of protesters gathered to demand that President Nicos Anastasiades resign after a Pandora Papers investigation showed that a law firm he’d founded had served as an offshore conduit for mega-wealthy Russians. “Enough is enough,” an opposition party leader told the rally. “For years, clouds have been gathering, until today’s storm broke out.”

In the U.S., Joshua Rudolph, an anti-corruption expert at the nonprofit Alliance for Securing Democracy, said American authorities should respond to the Pandora Papers “with sweeping and forceful policy reforms. . . . The latest jarring revelations expose how the U.S. financial system plays a central role in hiding the dubious wealth of corrupt officials. It suggests that the policy response, too, must be made in America.”

Like previous ICIJ reporting partnerships that zeroed in on offshore money, ICIJ’s latest investigation has reverberated in dozens of countries. One difference this time around is that the Pandora Papers investigation has sparked some of its biggest developments in the U.S. — a nation that has long criticized other countries for enabling money laundering and tax evasion even as the U.S. itself serves as a major hub for offshore money.

On Oct. 6, in response to Pandora Papers reporting by the Washington Post and ICIJ, a bipartisan group of U.S. lawmakers introduced legislation that would, for the first time, require trust companies, lawyers, art dealers and others to investigate foreign clients trying to move money through the American financial system.

At a congressional hearing devoted to the Pandora Papers in early December, lawmakers called out South Dakota and other U.S. states for copying the methods of the Cayman Islands and other traditional offshore financial havens. A story jointly reported by ICIJ and The Washington Post exposed South Dakota’s thriving and highly secretive offshore industry, including details of nearly 30 trusts that held assets linked to people or companies accused of fraud, bribery or human rights abuses. A Russian oligarch and an aide to a brutal former Latin American dictator also set up trusts and secretive companies in Wyoming, ICIJ and The Washington Post revealed.

Across the Atlantic, European Union officials promised new crackdowns on tax evaders and Europol, the continent’s anti-crime agency, said the journalism partnership’s findings will help it fight organized crime.

“The Pandora Papers prove that the current approach of exchanging nicely-worded letters simply doesn’t cut it,” Markus Ferber, a German member of the European Parliament, said during a hearing on the Pandora Papers.

In the United Kingdom, lawmakers blasted the U.K.’s continuing role as a destination and conduit for dirty money. “We need for our Government to wake up, stop mouthing warm words — which they do a lot — and start acting with tough measures to bear down on this dangerous crime and this terrible trend,” Margaret Hodge, a Labor Party member of Parliament, said.

Nigeria’s Code of Conduct Bureau announced it would probe politicians named in the Pandora Papers. Acknowledging past challenges holding powerful figures to account, Mohammed Isah, the head of the bureau, said, “Nigerians found to be involved in the Pandora Papers investigation will have a straightforward trial.”

Trouble for politicians

Other public officials were forced to defend their own financial dealings, or the offshore maneuvers of people close to them.

In Chile, lawmakers impeached President Sebastián Piñera in response to revelations that part of a $152 million sale of his children’s interest in a mining company was conditioned on the Chilean government not imposing certain environmental restrictions — the government led by Piñera at the time. Piñera denied any conflict of interest. Chile’s Senate voted 24-18 in favor of removing him from office, but the vote fell short of the required threshold.

In Ecuador, President Guillermo Lasso also survived an impeachment effort in response to revelations that he transferred assets to South Dakota months after the Latin American country passed a law banning officials from owning offshore companies. Lawmakers instead referred Lasso to the country’s prosecutor, tax office and other agencies to see if he broke any laws.

In Honduras, voters rejected Nasry Asfura — the ruling party candidate who had been favored to win the country’s November presidential election — after the Pandora Papers investigation exposed his interests in secretive companies in Panama.

The Philippines’ transportation secretary, Arthur Tugade, unexpectedly decided not to seek a Senate seat less than a week after journalists revealed he never declared a shell company in the British Virgin Islands, a declaration required by law.

In Sri Lanka, President Gotabaya Rajapaksa ordered an investigation into the Pandora Papers findings, including those showing members of his family used shell companies to buy luxury property and artwork.

The state prosecutor’s office in Montenegro questioned the son of President Milo Djukanovic after revelations that the family set up a complicated network of companies in five tax havens to manage inheritance and buy property. In Colombia, lawmakers summoned the country’s vice president, transportation minister and tax chief to testify after journalists revealed they each owned offshore companies.

Even prominent art museums have faced scrutiny.

In October, after the Pandora Papers investigation showed how a top art collector indicted for trafficking in looted artwork created two secretive offshore trusts, investigators from the U.S. attorney’s office met with the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York to scrutinize the origins of Cambodian artifacts in the museum’s collection. The meeting came days after the Denver Art Museum announced plans to return to Cambodia relics that were cited in reporting by ICIJ and The Washington Post.

“The Pandora Papers exposé confirmed that bad actors are exploiting the multibillion dollar art market, using legal loopholes to traffic artifacts, launder money, and hide ill-gotten gains,” said Tess Davis, executive director of the Antiquities Coalition.

Davis said public policy has generally “treated cultural racketeering as a white collar and victimless crime — if it treated it as a crime at all. High-profile and deeply-reported stories like the Pandora Papers do much to correct this false narrative.”

First Amendment journalism

The first revelations from the Pandora Papers rolled out at 1 p.m. EDT in the United States on Oct. 3. In under three hours, #PandoraPapers was the No. 2 trending topic on Twitter worldwide.

Along with hundreds of stories from the news outlets that were members of the partnership, other media around the globe also spread the word.

“Massive data leak exposes hidden wealth of world leaders,” a Financial Times’ headline said. Pakistan’s Express Tribune said: ‘Pandora Papers’ to open Pandora’s box.”

Based on almost 12 million confidential records from offshore service providers headquartered in four continents, the Pandora Papers revealed how presidents, prime ministers and even one king, as well as billionaires, celebrities and criminals, shielded vast fortunes through secretive companies set up in tax havens.

By sifting through records from 14 different offshore service providers, the Pandora Papers investigation brought unprecedented attention to long-standing tax havens, including Switzerland, Belize, and the Seychelles, as well as rising offshore hubs like the United Arab Emirates.

ICIJ obtained the leaked documents and shared them with the largest team of journalists in history. For almost two years, journalists from Jakarta to Istanbul to Montevideo to Washington, D.C. scoured the files, complementing and expanding on explosive disclosures with hundreds of interviews and thousands of pages of real estate, corporate and other records — public and confidential.

The investigation was highlighted in political cartoons in South Africa, The Netherlands, Italy, Ukraine, India and other nations; on TikTok accounts in Ukraine; and on “The Late Show with Stephen Colbert” in New York City. Colbert used the Pandora Papers as fodder for “the latest installment of my long-running segment: Rich People: They’re Just Not Like Us. Us Pay Taxes.”

National Public Radio’s comedy quiz show, “Wait, Wait, Don’t Tell Me,” opened with a segment asserting that “the hip, new, cool place to stash your ill-gotten gains is the sovereign state of South Dakota.”

One panelist quipped: “I guess that does explain all the tricked-out John Deere tractors you see in South Dakota with, like, gold-plated rims and $9,000 sound systems.”

In a more serious vein, Arkansas Democrat Gazette columnist Mike Masterson called the Pandora Papers an example of “an example of what First Amendment journalism should (and could be) if those directing many of the print and broadcast newsrooms across America were committed to their responsibilities to the American public.” Robert Silverman, senior advocacy manager for the anti-poverty group Oxfam America said the Pandora Papers were “a damning reminder that the United States has two separate tax systems — one for the uber rich and well-connected, and one for everyone else.”

Former Estonian President Toomas Hendrik Ilves pointed to the culpability of Western politicians, lawyers, bankers and accountants in offshore-enabled wrongdoing, saying the Pandora Papers “demonstrate that we ourselves are systematically complicit in the thievery and corruption that plague so many societies.”

In Costa Rica, tax authorities announced a probe into individuals and companies, including a major milk producer that set up a shell company in Panama months after being fined for tax evasion pulled off through a separate offshore scheme. Malaysia’s prime minister’s office also promised that national agencies would probe the Pandora Papers’ disclosures.

In the Netherlands, where the Pandora Papers revealed that Finance Minister Wopke Hoekstra held a secret interest in a shell company in the British Virgin Islands, the Parliament voted to close the loophole that had excused Hoekstra from declaring his offshore ties.

Authorities in Pakistan announced they had begun to collect Pandora Papers information for possible financial crimes and tax avoidance. In India, a group of government agencies also opened an inquiry, raising hopes of future fines and penalties. Previous investigations sparked by revelations from ICIJ helped India recover millions of dollars, the finance ministry announced in launching the Pandora Papers probe.

Tax havens also responded.

The Monetary Authority of Singapore, the East Asian nation’s central bank and financial regulator, announced probes into offshore firms with offices in the country.

In Belize, a Central American tax haven and home to three of the 14 offshore service providers whose leaked records formed the basis of the Pandora Papers, the country’s financial intelligence unit announced an investigation — and publicly praised the media collaboration.

“We place on record our appreciation for the value that investigative journalism brings to the process,” the unit said. “It assists the work of law enforcement and regulatory authorities by providing useful information from, at times, unconventional sources.”

A fracas in Prague

In the Czech Republic, Prime Minister Babis fought back. While the leaked records included a copy of his passport, signature and bank reference letters, Babis claimed that the media investigation was fabricated.

On the streets, his bodyguards pushed away reporters who dared ask questions. Journalists who broke the story received threats online. “There is boiling water waiting for you,” one Facebook user wrote.

The Pandora Papers dominated local and international news for days as the election campaign hit fever pitch.

“Sensation in Prague,” said a headline in the Austrian daily, Kurier. In the United Kingdom, The Independent told readers: “Scandal-ridden Babis, named in Pandora Papers, still set to win election.” In the Czech Republic, where free speech is curtailed and where Babis himself owns two newspapers and the country’s biggest commercial radio station, even newspapers friendly to Babis covered the story.

In Prague, political scientist Jakub Charvát told local newspaper Blesk.cz that no previous scandal had weakened Babis more. “If even this does not discourage voters, then perhaps nothing will discourage them,” Charvat said of the Pandora Papers as results were being tallied.

It did.

Voters showed one of Europe’s highest profile populists the door, with Babis losing by less than 1%.

Standing behind a podium with the political slogan, “I Will Fight For You,” Babis said: “We did not expect a loss.”

Contributors: Scilla Alecci, Jelena Cosic and Spencer Woodman