TAX AVOIDANCE

A global billionaire tax could generate $250 billion annually, researchers say

Tax havens continue to play a key role in helping billionaires and multinational corporations dodge taxes, according to a new report, which found that the ultra-rich pay almost no tax.

The world’s richest people are using shell companies to whittle down their tax bills, according to a new report by the EU Tax Observatory, which argues a global minimum tax rate for billionaires could raise $250 billion per year.

The research group, based at the Paris School of Economics, found that billionaires worldwide have effective personal tax rates of between 0% and 0.5% — well below those of ordinary taxpayers. By taxing 2,700 billionaires just 2% of their wealth annually, researchers estimated that countries could raise the revenue needed to respond to global crises, from soaring income inequality to climate change.

In the foreword of the report, titled Global Tax Evasion Report 2024, economist and Nobel Prize laureate Joseph Stiglitz said that beyond the need for government investment in services and infrastructure, glaring tax disparities also undermine democracy by eroding trust in institutions.

“If citizens don’t believe that everyone is paying their fair share of taxes — and especially if they see the rich and rich corporations not paying their fair share — then they will begin to reject taxation,” Stiglitz said in the report.

If citizens don’t believe that everyone is paying their fair share of taxes … then they will begin to reject taxation.

— Joseph Stiglitz, Nobel Prize-winning economist

In addition to taxing billionaires, the researchers proposed strengthening the global minimum tax rate for multinational corporations to raise an additional $250 billion per year.

Stiglitz told ICIJ that simply taxing billionaires would not on its own end global tax abuse, or solve inequality; it is also necessary to adequately tax corporations that generate disproportionately high incomes for the ultra-wealthy.

“If the money stayed in corporations and they invested in new enterprises that would be one thing, but the money typically goes to rich people. Not taxing multinational corporations has provided a flow of wealth to a few people,” Stiglitz said.

The report also found that moves to clamp down on corporate profit shifting have stalled over the past seven years. In 2022, multinationals continued to book about 35% of foreign profits in tax havens, totaling an estimated $1 trillion globally, researchers said.

ICIJ investigations such as the Paradise Papers and Luxembourg Leaks have highlighted the staggering scale of corporate tax dodging by some of the world’s biggest companies. In 2017, the Paradise Papers revealed tax maneuvers by more than 100 corporations, including Nike, Uber and Apple, the latter of which shifted profits around the world to amass $252 billion offshore.

Stiglitz cited Apple as an example of a massively successful company that had enriched a handful of individuals because it was not properly taxed. “Money that would have gone to the people has now gone to rich individuals. We now have a responsibility to get it back,” he said.

In 2021, nearly 140 countries reached a landmark global tax agreement, which included a commitment by governments to set a minimum tax rate of 15% for multinationals. But the Tax Observatory’s report warned that the reforms had since been “dramatically weakened by a growing list of loopholes.”

For example, companies can effectively sidestep the 15% tax rate by demonstrating economic activity in low-tax countries, which both incentivizes firms to move production to tax havens and encourages tax havens to keep tax rates low, researchers said. In August, a separate report by the Tax Justice Network advocacy group estimated that tax havens could cost countries $4.7 trillion in tax revenue over the next decade.

But while the problem of tax evasion persists, the Tax Observatory found that significant progress has been made in the past decade to expose murky offshore tax arrangements, including by curtailing banking secrecy. The report found that the implementation of an automatic information exchange system has allowed tax authorities to more easily share and access financial data across borders, and has contributed to a reduction in offshore tax evasion by a factor of three.

Other relatively new sources of information, such as ICIJ’s 2016 Panama Papers leak and government probes into taxpayers’ offshore assets, have also helped lift the veil on the offshore financial system, researchers said. However, while developments in international tax cooperation have dramatically limited the scope for hiding accounts offshore, wealthy people are avoiding scrutiny by tax authorities in other ways.

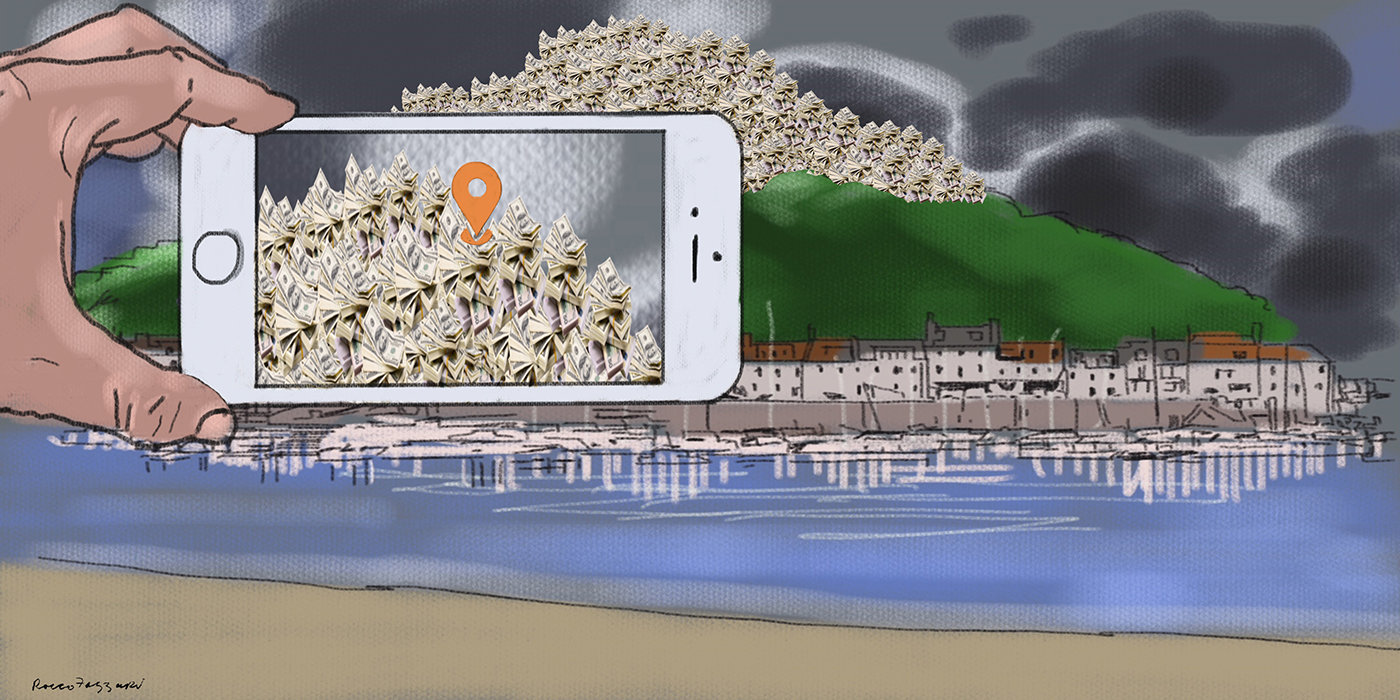

One “particularly serious blind spot” in the banking information exchange system, according to the Tax Observatory report, is that money once stashed in offshore accounts is instead being invested in real estate through secretive structures such as shell companies and trusts.

Researchers estimated that close to $500 billion worth of real estate in six cities with available data is owned by foreign entities, which are also used to obscure ownership by residents. In the United Kingdom, for example, around 1.25% of residential real estate was owned offshore but the share increased to 15% for top-end properties.

While the banking system effectively tracks financial assets, other assets — such as luxury property, private art collections and superyachts — can pass under the radar undetected and untaxed.

Stiglitz suggested that taxing such assets when they come on the market and are monetized may be one way to ascertain the assets’ otherwise uncertain values. But he reiterated that bolstering and standardizing tax rates for billionaires and multinationals is the most efficient way countries can fight tax evasion on a global scale.

“We have a framework where we can have relatively good, not perfect, but relatively good global wealth tax,” Stiglitz said.