Among the many corporations using offshore havens to reduce tax bills is Blackstone Group, the New York-based private equity firm run by Stephen Schwarzman, a billionaire who has been one of President Trump’s closest allies on Wall Street.

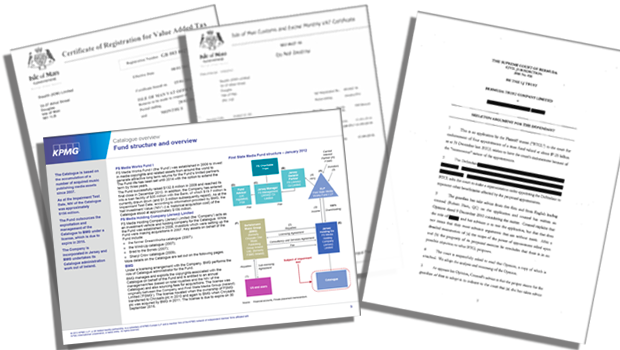

Hundreds of pages of leaked documents from the Paradise Papers detail how the private equity giant routed its ownership of two large U.K. commercial rental properties through a string of subsidiaries in two well-known tax havens: Luxembourg and the island of Jersey, a U.K. dependency off the coast of France.

Under the structure, renters in the U.K. would effectively pay rent to a Jersey-based trust fund that would ultimately transfer the money to Blackstone subsidiaries in Luxembourg, according to the confidential documents. The records describe plans for large loans to pass between the Blackstone subsidiaries holding the U.K. properties. These loans appear to have shifted Blackstone’s profits from the U.K. to Luxembourg avoiding any tax anywhere, according to Reuven Avi-Yonah, professor and tax expert at University of Michigan Law School.

In response to questions about these tax structures, a law firm for Blackstone sent ICIJ a statement saying, “Blackstone’s investments are wholly compliant with U.K. and international tax laws and regulations.” Blackstone said that it had acquired these structures “from institutional investors” and that the arrangements were commonplace for such real estate investments and had been used for decades in the U.K. The configurations, according to the statement, “were adopted after appropriate advice was taken from leading tax and legal advisors.”

Today, ICIJ is releasing two confidential reports that provide detailed descriptions of these maneuvers. These reports were prepared for Blackstone by two giant accounting firms, PriceWaterhouseCoopers and Deloitte. You can read them in full below.

Avi-Yonah reviewed the Blackstone reports at ICIJ’s request and spoke about them in the following Q&A with ICIJ reporter Spencer Woodman. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Spencer Woodman: Do these Blackstone structures share similarities with other methods of corporate tax avoidance that you’ve seen?

Reuven Avi-Yonah: Yes. Generally, the idea is that you want to shift income from entities located in comparatively high-tax jurisdictions like the U.K. to other entities in relatively low-tax jurisdictions, like Bermuda or Jersey.

W: What’s your takeaway from these Blackstone documents in particular?

A: My sense is that both transactions are pretty similar. They manipulate the tax structures in sometimes fairly aggressive ways in order to achieve a result of both a deduction that Blackstone can use to reduce its taxable income in the U.K., plus no withholding tax (tax U.K. authorities retain before income departs the country).

W: Is this what you have called “double non-taxation”? What is that?

A: In my mind, it refers to when two countries do not tax any income of a company (with a corporate presence of some kind in both), allowing that income to be accumulated in the lower-tax jurisdiction.

W: Can you give a summary of the purpose of the loans made between the Blackstone firms in Luxembourg?

A: They’re moving income in the form of interest payments from where the properties actually are to Luxembourg, which is famous for not taxing foreign-sourced income.

Interest that comes from the U.K., or any other country, can go untaxed in Luxembourg.

There are special rulings whereby the Luxembourg tax administration enters into sweetheart deals with various companies to subject them to a tax rate that is way below the nominal tax rate. (However, the exact terms of Blackstone’s tax treatment in Luxembourg are not clear.)

And the problem with something like that is that Luxembourg appears to be a good citizen of the E.U. in the sense that it has a nominal high tax rate and has a treaty network — it’s not Bermuda, it’s not an official tax haven. And yet, under the table, it does these things that result in a very, very low tax rate.

So Luxembourg plays the role of tax haven in this story, similar to that typically played by Bermuda or the Caymans. But because it is a member state of the E.U. and it has treaty networks and so on, it is possible to move income — perhaps in the form of interest payments — from the U.K. to Luxembourg without being subject to withholding tax in the U.K.

Editor’s Note: In 2014, ICIJ’s Lux Leaks files detailed confidential tax rulings from Luxembourg officials that grant companies favorable treatment for moving their income to the country.

W: In terms of these intercompany loans, what is the purpose of the interest payments between Blackstone’s subsidiaries?

A: Generally, interest payments on a loan is deductible from corporate income taxes. If you have a hundred pounds of income and you pay 90 pounds in interest then you only pay tax on ten. It’s a much smaller tax than if you didn’t have the 90 percent interest deduction.

W: And in the Blackstone case, to whom is this interest actually being paid?

A: Well, the interest payments follow the inter-company loans and ultimately end up in Luxembourg — subject to a very reduced tax rate – and so the money can then sit there and pay no tax.

W: Can you talk about taxes on rental income in the context of these Blackstone documents?

A: These properties obviously generate significant income, especially in London, which is a very expensive place to live and to have offices. All of that income would be normally subject to full U.K. income tax and even though the U.K. has repeatedly cut its corporate tax rate, it’s still something like 19 percent, so it’s not like zero or anywhere close to it. I think HRMC [Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs] could be significantly concerned about a transaction in which this type of income is not subject to tax because it is offset by deductible items going to a jurisdiction where it is taxed at zero-point-zero-one percent or whatever it is. And that appears to be what’s happening here.

Chiswick Park 2013 Tax Structure Report 1 (Text)