U.S. Commerce Secretary Wilbur L. Ross Jr. has a stake in a shipping firm that receives millions of dollars a year in revenue from a company whose key owners include Russian President Vladimir Putin’s son-in-law and a Russian tycoon sanctioned by the U.S. Treasury Department as a member of Putin’s inner circle.

Ross, a billionaire private equity investor, divested most of his business assets before joining President Donald Trump’s Cabinet in February, but he kept a stake in the shipping firm, Navigator Holdings Ltd., which is incorporated in the Marshall Islands in the South Pacific. Offshore entities in which Ross and other investors hold a financial stake controlled 31.5 percent of the company in 2016, according to Navigator’s latest annual report.

Among Navigator’s largest customers, contributing more than $68 million in revenue since 2014, is the Moscow-based gas and petrochemicals company Sibur. Two of its key owners are Kirill Shamalov, who is married to Putin’s youngest daughter, and Gennady Timchenko, the sanctioned oligarch whose activities in the energy sector, the Treasury Department said, were “directly linked to Putin.”

Another powerful owner is Sibur’s largest shareholder, Leonid Mikhelson, who controls an energy company that was also sanctioned by the Treasury Department for propping up Putin’s rule.

As commerce secretary, Ross has direct authority over trade and manufacturing policy and is an influential voice in the government on virtually any aspect of the U.S. economic relationship with other countries, including Russia. In recent years, tensions between the United States and Russia have escalated, with the United States imposing sanctions against Russia after its 2014 invasion of Crimea and its interference in the 2016 presidential election.

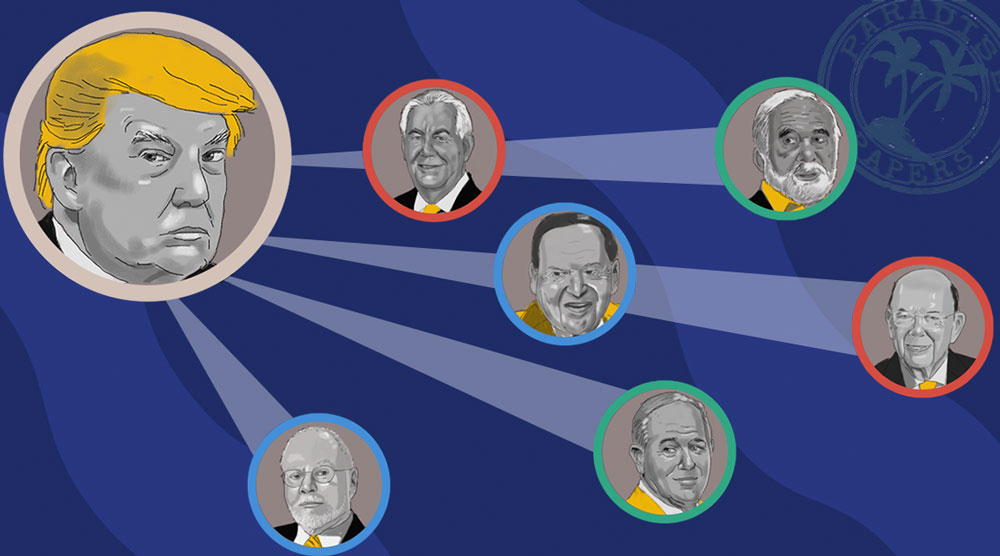

In the aftermath of the election, investigations by Congress and the U.S. Justice Department have explored potential business ties between Russia and members of the Trump administration. While several of Trump’s campaign and business associates have come under scrutiny, until now no business connections have been reported between senior Trump administration officials and members of Putin’s family or inner circle.

During his confirmation process, Ross was asked repeatedly about his business ties to Russia, mostly related to his former role as vice chairman of the Bank of Cyprus, which has a long history of financing Russian oligarchs. “The United States Senate and the American public deserve to know the full extent of your connections with Russia and your knowledge of any ties between the Trump Administration, Trump Campaign, or Trump Organization and the Bank of Cyprus,” a group of five Democratic senators wrote Ross after the hearing but prior to his confirmation. Ross responded briefly to a question submitted for the hearing, saying the Russians who invested in the bank “were not my partners,” but he didn’t respond to the senators’ letter.

He was also asked about his shipping holdings and whether they could pose a conflict of interest with his duties at Commerce. But he faced no questions about Navigator – where his private equity firm was once the majority shareholder and Ross was a member of the board – and its relationship with Sibur.

Why would any officer of the U.S. government have any relationship with a Putin crony?

Sibur is “a company with crony connections,” said Daniel Fried, a Russia expert who served in senior State Department posts in both Republican and Democratic administrations. “Why would any officer of the U.S. government have any relationship with a Putin crony?”

Ross joined the board only after Navigator began dealing with Sibur and “never met” Shamalov, Timchenko or Mikhelson, said James Rockas, a spokesman for the Commerce Department.

“Secretary Ross recuses himself from any matters focused on transoceanic shipping vessels, but has been generally supportive of the administration’s sanctions of Russian and Venezuelan entities,” Rockas said.

Another of Navigator’s major customers is PDVSA, the Venezuelan state-owned oil company controlled by the authoritarian regime of Nicolas Maduro. The Trump administration sanctioned one current and one former executive at PDVSA in July 2017, and sanctioned the company itself the next month.

Commerce and conflict

The commerce secretary’s indirect business connection with Putin’s son-in-law and oligarch allies emerges from an examination of public records and a leak of millions of offshore financial documents from the Bermuda law firm Appleby obtained by German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung and shared with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and its global network of media partners. They represent the inner workings of Appleby from the 1950s until 2016. The files include documents from Appleby’s corporate services division, which became independent in 2016 under the name Estera.

The leaked files showed a chain of companies and partnerships in the Cayman Islands through which Ross has retained his financial stake in Navigator.

The fact that Ross’ Cayman Islands companies benefit from a firm controlled by Putin proxies raises serious potential conflicts of interest, experts say. As commerce secretary, Ross has the power to influence U.S. trade, sanctions and other matters that could affect Sibur’s owners. Likewise, Sibur’s owners, and through them, Putin himself, could have the ability to increase or decrease Sibur’s business with Navigator even as Ross helps steer U.S. policy.

Richard Painter, who served as chief ethics lawyer during the George W. Bush administration, said Ross might have to recuse himself from a range of sanctions decisions. He added that while there was no inherent violation in Ross’ holdings, the Navigator arrangement warrants closer scrutiny.

Commerce spokesman Rockas said that Ross “has never had to seek, nor received, any ethics exemption” and abides by the “highest ethical standards.” Ethics exemptions are granted to allow officials to participate in issues where there might be a conflict of interest.

“Apart from those legal issues, I’d be very concerned that someone in the U.S. government was making money from dealing with the Russians, and I’d want to know the facts,” Painter said.

Layers and layers and layers and layers

Before joining the Trump Cabinet, the 79-year-old Ross was a titan in the world of private equity, rounding up investors from around the world to put money into troubled companies in the hope of profitably turning them around. When all went well, he and his firm made money not only on their investments and management fees but also from a compensation system that allows the general partners, who manage private equity funds, to earn 20 percent of any profits that exceed a certain level.

Many of the private equity funds involved in these investments were created and administered by Appleby, an offshore law firm founded in Bermuda . The leaked files offer a window into how Appleby helped his firm, WL Ross & Co. LLC, reap the benefits of offshore havens such as the Cayman Islands, a British territory that permits extraordinary levels of financial secrecy and allows paper companies run from New York and elsewhere to operate there tax-free. In 2015, the Cayman Islands was ranked fifth by the Financial Secrecy Index in its worldwide ratings.

Creating offshore funds organized as corporations can be a major draw for certain investors, by allowing U.S. tax-exempt organizations – including huge pension funds and richly endowed universities – to sidestep an Internal Revenue Service rule the requires them to pay taxes on income obtained using borrowed money. They also help attract non-U.S. investors because their names aren’t disclosed to tax authorities in the United States.

General partners in offshore private equity enjoy generous tax breaks in the United States as well, including the ability to count the biggest share of their earnings from the fund as a long-term capital gain, rather than ordinary income. This allows the wealthiest fund managers to reduce the tax on these earnings from the top U.S. rate of 39.6 percent to 20 percent.

When he was nominated as commerce secretary, Ross filed an agreement with the federal Office of Government Ethics that said he intended to divest 80 companies and partnerships, but would keep a stake in nine others that held assets in “real estate financing and mortgage lending” and “transoceanic shipping.” The assets were not specified. Even though he had sold WL Ross & Co. to Invesco in 2006, he remained active as chair and CEO until resigning to join the Cabinet.

His financial disclosure form, also filed with the Office of Government Ethics, runs 57 pages and includes a long list under the heading, “Employment Assets & Income and Retirement Accounts.” This list is broken down into sections listing assets that appear to be held by each of Ross’ companies, detailing as many as seven layers of entities between Ross and the assets he holds.

Buried in a multitude of subsections appear four cryptically named Cayman Islands entities that are among those he said he was keeping: WLR Recovery Associates IV DSS AIV, GP; WLR Recovery Associates IV DSS AIV, LP; WLR Recovery Associates V DSS AIV, GP and WLR Recovery Associates V DSS AIV, LP. All four companies are administered by the Appleby law firm. “Navigator Holdings” is listed among the assets these companies held, but, consistent with the format of the disclosure form, no details about the company or its relationship with Sibur are provided.

The complexity of the offshore structures adds legal and reputational distance and obscures the full extent of Ross’s business relationships even as it allows him to profit from them, according to tax and ethics experts consulted by ICIJ.

Ross’ disclosure values his combined current stake in the offshore entities that hold Navigator shares at between $2.05 million to $10.1 million. But it is not certain what his total holdings are because he did not list a value for one of the four entities he retained. It is not apparent why or whether a value was omitted. His share represents a fraction of the entities’ overall 31.5 percent stake in Navigator, which, based on the firm’s stock price on Oct. 30, 2017, is worth roughly $179 million.

The value of Ross’ investment could change substantially by the time the funds that hold Navigator shares wind up – and holds a significant upside. If the funds performs well enough, the general partnerships in which he is invested stand to receive 20 percent of the entire funds’ profits.

In addition, Ross has reported billions in assets to Forbes magazine that did not appear on his government disclosure forms, which he later told the magazine he had placed in trusts that benefit his family members.

“The disclosure requirements weren’t written with Wilbur Ross in mind,” said Kathleen Clark, a law professor at Washington University in St. Louis and an expert on government ethics, “and I don’t think adequately provide the public or a government ethics official with an understanding of the wide variety of financial interests that he has.”

Wilbur Ross hits a home run

Ross started investing in Navigator in 2011, when WL Ross & Co. acquired a 19.4 percent stake, and his firm was granted two seats on Navigator’s board, one of which Ross filled himself early the next year. A few months later, with a bankruptcy court judge’s approval, WL Ross acquired a block of shares from the bankrupt financial services firm Lehman Brothers, becoming Navigator’s majority shareholder.

In November 2013, Navigator went public. Shares that WL Ross had bought for about $8 each were put on the market at $19. Afterward Ross bragged at a conference for shipping investors that the investment had been “a home run.”

Ross stepped down from Navigator’s board in November 2014 after he became vice chairman of the struggling Bank of Cyprus, which was well known for its dealings with Russian oligarchs. His Navigator board seat was taken by Wendy Teramoto, managing director and partner of WL Ross & Co., who left in 2017 to become Ross’ chief of staff at the Commerce Department.

Navigator meets Sibur

In early 2012, not long after Ross made his initial investment, Navigator struck up a relationship with Sibur, which exclusively chartered two liquified petroleum gas carriers to transport its growing LPG exports to Europe.

Like many Russian energy companies, Sibur was created by the Russian state. Founded in 1995, the firm produces petrochemical products including LPG, which contains propane and butane and is used for heating appliances, cooking equipment and some motor vehicles. Sibur was bought several years later by the state-controlled gas company Gazprom.In 2010, Gazprom sold Sibur to Timchenko and Mikhelson.

Amos Hochstein, the top U.S. energy diplomat during the Obama administration, said Mikhelson and Timchenko’s trajectories were typical of Russian energy moguls who have grown rich as a result of the public corruption and crony capitalism that are hallmarks of Putin’s long rule.

“This is not John D. Rockefeller here,” Hochstein said. “They became close to Putin, loyal to Putin, got state assets and got rich.”

The Russian government continues to favor Sibur. In 2013, Sibur’s export terminal in Ust-Luga, the Baltic port where Navigator ships pick up LPG exports, was completed as “part of the federal program for development of port capacities,” according to a Sibur press release.

When you start doing business with Russian energy companies like Gazprom and Sibur, you’re not just getting into bed with the company … You’re getting into bed with the Russian state.

After Russia’s invasion of the Ukrainian region of Crimea and afterwards, the United States and other Western nations imposed economic sanctions on key Putin allies, including Sibur’s second-largest shareholder, Timchenko. A few months later, the United States barred banks from providing long-term financing to a gas company belonging to Sibur’s largest shareholder, Mikhelson.

Sibur itself was not targeted, but Western banks, including Bank of America and the Royal Bank of Scotland, backed away from making loans to the company, according to news reports.

The Russian government again stepped in to help. In May 2014, a consortium led by a state-run bank affiliated with Gazprom and a state investment fund bought the Ust-Luga terminal from Sibur and pledged to expand export capacity while allowing Sibur to remain the terminal’s sole exporter of LPG.

In September 2014, with sanctions pressure growing, Timchenko sold a 17 percent stake in Sibur to Shamalov, then 32, increasing Putin’s son-in-law’s stake to more than 20 percent of the company. The purchase by Shamalov was financed by a $1.3 billion loan from state-owned Gazprombank. Shamalov later sold part of his stake to other investors, reducing his interest to 3.9 percent by April 2017 but remaining on Sibur’s board of directors. Shamalov’s profit or loss on the transactions could not be determined.

“When you start doing business with Russian energy companies like Gazprom and Sibur, you’re not just getting into bed with the company,” said Hochstein, the former State Department energy policy coordinator. “You’re getting into bed with the Russian state.”

In 2014, Appleby dropped Mikhelson as a client, declining to manage a company for his private jet because of the sanctions against his businesses, according to the leaked records.

Despite the turmoil, the Navigator-Sibur relationship continued to grow. From 2014 to 2015, the shipper’s revenue from Sibur jumped from 5.3 percent ($16.2 million) to 9.1 percent ($28.7 million) of total revenue, making the company one of Navigator’s top five clients, according to filings with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, before sliding down to 7.9 percent ($23.2 million) of revenue last year. This year, Navigator doubled the fleet dedicated to Sibur exports, acquiring two new vessels chartered by the Russian energy company. The ships were named Navigator Luga and Navigator Yauza, after Russian rivers.

In a conference call with investors in 2016, Navigator CEO David Butters said his company benefited as Sibur made inroads into the European energy market over American competitors.

“Russia is pipelining as much natural gas as needed into Europe, and liquids are being shipped into all areas of the continent in increasing amounts, all in competition with longer haul U.S. exports,” Butters said.

Ross “has repeatedly spoken in favor of increasing U.S. exports as the best way to reduce the trade deficit, creating American jobs,” said the Commerce Department spokesman.

Butters declined to comment for the story. In an emailed statement, Sibur said that its business partners performed “all necessary checks” after the United States and other nations sanctioned Russia in 2014, and that no restrictions on cooperation were identified.

A toast

On Nov. 30, 2016, hours after being nominated as commerce secretary, Ross celebrated at Gramercy Tavern, an upscale Manhattan restaurant, an event hosted by Navigator Holdings. According to Bloomberg Businessweek, he and Butters arrived early at the chandeliered private room and had a conversation.

“Your interest is aligned to mine,” Butters recalled Ross saying, according to Bloomberg. “The U.S. economy will grow, and Navigator will be a beneficiary.”

Butters told Bloomberg that as other guests arrived and tucked into sherry-sauce sea bass and pear buckle, they took turns congratulating Ross. “It was like – we have a chance now,” Butters told Bloomberg. “We have a chance to make some differences.”

Making billions from bankruptcies

The son of a lawyer-turned-judge and a schoolteacher, Ross was raised in suburban New Jersey and graduated from Yale and Harvard Business School. In the late 1970s, he joined the British investment banking firm Rothschild Group, eventually rising to lead the firm’s bankruptcy advisory practice. He met Donald Trump in 1990 when the future president’s Taj Mahal casino in Atlantic City was experiencing financial trouble and Ross represented a group of bondholders. Ross engineered a deal that preserved a stake in the company for Trump, reportedly telling disgruntled bondholders that the Trump name was “still very much an asset.” It was a welcome assist for the future president.

In the 1990s, President Bill Clinton appointed Ross to the board of the U.S.-Russia Investment Fund, established by the government to make investments and promote American business interests in Russia.

In 2000, Ross founded WL Ross & Co. LLC, a New York-based private equity firm that assembles money from investors into funds that invest in struggling companies with the goal of turning them around and selling them for a profit. The new firm quickly thrived. It engineered the purchase of bankrupt American steel producers and reaped huge profits when the George W. Bush administration imposed a 30 percent tariff on steel imports in March 2002.

His newly formed International Steel Group went public the next year and was acquired by Luxembourg giant ArcelorMittal in 2005. Ross’ firm went on to invest in other struggling American industries, including textiles in the South and coal in Appalachia. Ross gained a reputation as a financier who breathed life into industries others had left for dead.

But he has been criticized for moving American jobs overseas to improve profits. A Reuters’ analysis of U.S. Labor Department statistics found that Ross takeovers resulted in the loss of 2,700 U.S. jobs in auto parts, mortgage finance and textiles by shifting production abroad, benefiting Mexico, India, China and Nicaragua, among other countries.

His private equity firm has also run afoul of securities regulations that require full and candid disclosure in dealings with investors. In August 2016, the SEC announced an enforcement action against WL Ross & Co. for overcharging investors by changing the formula for calculating management fees without telling them. Without admitting or denying wrongdoing, WL Ross agreed to pay $10.4 million in restitution to investors and $2.3 million in civil penalties.

Over the years, Ross has climbed into the ranks of America’s wealthiest individuals, with a fortune estimated by Forbes in September 2017 at $2.5 billion. He and his wife, Hilary Geary Ross, have a Palm Beach villa down the road from Trump’s Mar-a-Lago resort in Florida, another house in Southampton, N.Y., and a third home in Manhattan. They also own an art collection with a value that Bloomberg has estimated at $250 million, including paintings by the surrealist Rene Magritte valued at $100 million.

Ross was also leader – known as the Grand Swipe – of a secret Wall Street fraternity called Kappa Beta Phi and in 2012 presided over an annual ceremony in which initiates performed song-and-dance routines in drag during a feast of lamb and foie gras at a Manhattan hotel.

Ross has dismissed the idea that the very wealthiest have unfair advantages, arguing in 2014 that “the 1 percent is being picked on for political reasons.” He added, ““Education is the way that people get out of the ghetto and into, if not the 1 percent, something close to it.”

Trump said he nominated Ross because he admires his wealth and ferocious drive. “I’d like to put on a guy that failed all his life, but we don’t want that, do we?” Trump said at a post-election victory rally in Ohio. “No, I put on a killer.”

And Appleby was there

As it expanded, WL Ross & Co. set up an increasing number of entities in offshore tax havens, many in the Cayman Islands. The British territory in the Caribbean levies no corporate or income tax on money earned outside the jurisdiction and requires little disclosure of corporate ownership. This has made the Caymans a popular place for U.S. private equity managers to set up their funds.

Appleby has been a key adviser and service provider. The global offshore law firm has administered more than 50 Cayman Island companies for WL Ross & Co., the law firm’s records show. Appleby’s files, for instance, include a group of five Cayman Islands companies whose names all include “Euro Wagon.” These companies were used to hold and manage shares of VTG, the German rail car and logistics company that WL Ross & Co. acquired in 2005 and that later expanded into Eastern Europe and Russia.

Appleby hosted and wooed WL Ross & Co. executives at such events as the U.S. Open tennis tournament, and employees congratulated one another as the relationship grew. The law firm reduced due diligence requirements for the Ross-related companies, by designating them low-risk and therefore qualified for decreased scrutiny under Cayman laws regulating law firms’ responsibility to investigate clients. “This is absolutely fantastic Sabine,” wrote Appleby attorney Matthew Taber, when compliance officer Sabine Calvetti broke the news about the need for less scrutiny. “100 percent spot on and really great work.”

In 2014, the Ross group was one of Appleby’s top 20 clients, based on the number of companies administered.

Appleby’s files show the four companies Ross retained in two parallel chains of ownership, with Ross at the top. According to Appleby records, Ross is a shareholder and was a director of two companies established in July 2011 as general partners to control two other WL Ross & Co entities that invested in the shipping industry, which, in turn, control two WL Ross Group funds.

These funds invested in several shipping companies, including Navigator, according to SEC filings and Ross’ ethics disclosures.

Ross’s former firm, WL Ross & Co., is Navigator’s largest shareholder, owning 39.4 percent of Navigator through companies it controls. After he became commerce secretary, Ross kept a personal financial interest in some of those entities but resigned from managing them. Those in which he retained a stake account for four-fifths of the overall 39.4 percent.

Federal ethics law requires officials to recuse themselves from matters that would have “a direct and predictable” effect on the official’s or a family member’s financial interest. Recusal is also required if the official has a close relationship that might cause a reasonable person to doubt the official’s impartiality.

During his confirmation hearings, Ross sought to reassure senators that he would avoid conflicts of interest between his business holdings and his Cabinet post. “I intend to be quite scrupulous about recusal and any topic where there is the slightest scintilla of doubt,” he said