In 2005, Russian President Vladimir Putin, already among the most powerful people on earth, set his sights on an unlikely place of interest: a tiny one-bedroom apartment on the second floor of a concrete building in central Tel Aviv.

During a state visit to Israel that year, Putin reunited with a Russian woman who had been one of his high school teachers in St. Petersburg, then called Leningrad. After a brief get-together, he began sending her small gifts and then, she said, arranged to buy a $208,000 apartment for her.

“When I moved to this apartment I cried,” Mina Yuditskaya-Berliner recalled nearly a decade later when she told the story to the Israeli publication Ynet. “Putin is a very grateful and decent man.”

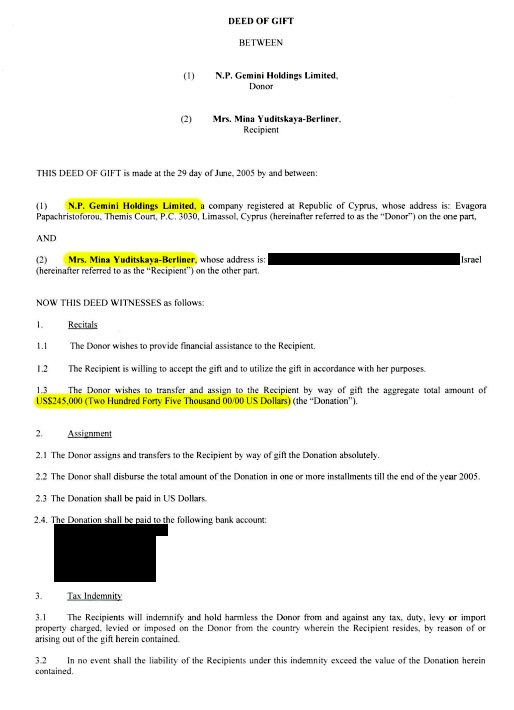

Seeming to qualify as one of the few heartwarming stories about Russia’s ruthless leader, the story made headlines in Israeli papers. Except that the money to buy the apartment didn’t come from Putin. Instead, newly uncovered financial records show that the true source of the funds was an offshore account controlled by Russian billionaire Roman Abramovich. The records include a “deed of gift” recording the transfer of $245,000 from an Abramovich-controlled company in Cyprus to Yuditskaya-Berliner on the same day she purchased the small apartment in central Tel Aviv.

The receipts provide evidence of a financial relationship that the two men have long downplayed or denied. Abramovich has disputed any such connection for decades. He even filed suit to quash reporting that suggests he has done Putin’s bidding.

The documents are part of a trove obtained by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, The Washington Post and the Israeli publication Shomrim.

Abramovich’s funding of the apartment “perfectly encapsulates how unwritten understandings and winks-and-nods lie at the heart of the Putin-era system,” said Andrew Weiss, an expert on Russia at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

The payment is significant because it places Abramovich at the center of a transaction of clear personal significance to Putin, providing a pinhole view into a Russian system of patronage and hidden wealth whose mechanics are normally obscured.

‘Putin’s cashier’?

The documents have surfaced at a time when Abramovich is fighting to protect a business empire besieged by sanctions imposed by Western governments after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The previously undisclosed files are likely to complicate that effort by undercutting his denials of any financial connections to Putin.

As far back as 2010, a representative for Abramovich insisted that the oligarch “has no financial relationship of any kind with … Putin,” in a comment provided to The Guardian newspaper.

“The allegation is entirely absurd,” Abramovich’s representative said.

More recently, a lawyer for Abramovich declared in a British court that the oligarch had been defamed by a book depicting him “as Putin’s cashier and the custodian of Kremlin slush funds.” The suit was settled last year after the publisher, HarperCollins, said it had been made aware that the book contained inaccurate information about Abramovich and apologized. (The author, Catherine Belton, now works for The Washington Post.)

Despite the scorched-earth tactics used to suppress such assertions, the documents make clear that Abramovich had played a silent, supporting role years earlier in buying a home for a woman who taught the Russian president German in the 1960s at High School 281 in Leningrad. Yuditskaya-Berliner immigrated to Israel in 1973 after growing weary of what she called the “suspicion, terror and fear” that characterized Soviet governance.

She recounted the story of Putin’s purported generosity in a 2014 article bearing the headline: “I was Vladimir Putin’s teacher.” Yuditskaya-Berliner described the teenage Putin as an excellent student, although he would often miss class to take part in wrestling training. She said she had since lost track of Putin – who went on to serve as a KGB operative in East Germany – until seeing him beside Russian President Boris Yeltsin on television in the late 1990s.

At the time, Yeltsin had tapped Putin to serve as head of Russia’s internal security service. In 1999, Putin vaulted to the top of the Russian government when he was named prime minister and acting president. Six years later, when the retired teacher saw reports that Putin was scheduled to visit Israel, she decided to take a chance. “I went to the Russian consulate and said that I just want the chance to look at him,” she explained.

Instead, Yuditskaya-Berliner, who was then a widow well into her 80s, got far more.

When Putin arrived in late April 2005, Yuditskaya-Berliner was taken in a bus to a hotel in Jerusalem, where Putin joined her in a private room, and they chatted over cups of tea. Putin joked about how much hair he had lost since his high school days, she recalled, and asked how she could endure the Israeli heat. Before departing, Putin asked her to scribble her address in a notepad. Then gifts began arriving, including a Russian watch and a copy of Putin’s autobiography bearing a personal inscription he had written on the title page.

After that came a knock on the door; it was a visitor who informed her that Putin wanted to buy an apartment for her, according to Ynet. She was renting at the time.

“Everything happened quickly from there,” she said. “Within a few months, movers arrived, packed my apartment… and moved me.”

Yuditskaya-Berliner made no mention of Abramovich or any other benefactor in her retelling. But the documents provide deeper visibility into the transaction.

The deed of gift is dated June 29, 2005, two months after Putin’s visit to Jerusalem. It lists Yuditskaya-Berliner as the recipient of $245,000 transferred that same day by N.P. Gemini Holdings Ltd., a Cyprus-based shell company.

Abramovich’s name does not appear on the deed or Gemini corporate filings in Cyprus, a secretive tax haven with a long record of catering to Russian oligarchs.

But other leaked documents and 2008 filings from a London court case clearly identify Abramovich as the owner of Gemini. A diagram shows Gemini at the center of a constellation of companies under an Abramovich-run trust. Additional clues are found in other documents, including records showing that Gemini held a stake in Sibneft, a large Russian oil company that Abramovich controlled until it was sold in 2005.

In an email, a spokesperson for Abramovich acknowledged the gift to the Russian president’s former teacher but said that it was made not at Putin’s behest but “following a request received from the Jewish community.” The spokesperson also said that “it would be false and sensational to suggest that anyone ‘had control’ over Mr. Abramovich finances based on a $240,000 donation – not least when Mr. Abramovich has donated over $500 million towards Jewish causes.”

Putin’s principal spokesman, Dmitry Peskov, did not directly respond to questions about Putin’s role in the transaction. Instead, he referred questions about the matter to the Federation of Jewish Communities of Russia, saying that “any charitable work in Israel would have been done by them.”

A representative for Abramovich said in an email response to submitted questions that the gift to Yuditskaya-Berliner was arranged by Rabbi Alexander Boroda, the president of the Federation of Jewish Communities of Russia. Shortly after reaching out to Putin’s spokesperson, reporters received an email from Alexander Boroda saying that he was “personally in contact with Ms. Yuditskaya-Berliner in 2005 regarding her living conditions as part of our extensive charitable work providing support to elderly citizens.” Boroda said that Yuditskaya-Berliner’s apartment “had a leaking roof and was located on the 4th floor without access to an elevator,” and said that, in seeking to help her, “we reached out to our key donors to seek support.”

Boroda said he could not provide any evidence to support his account of the transaction because it “was nearly 20 years ago.” An email sent by the Abramovich representative included an image of the cover page of the deed marked informally with Russian handwriting indicating that it had been “sent to Rabbi Boroda for approval.” No such handwriting appears on several versions of the deed found in the trove of leaked documents. Boroda is said to be a confidant of Vladimir Putin, according to the Forward, and has been criticized for appearing to voice support for the Russian president’s false claim of invading Ukraine to achieve “denazification” of the nation, according to the Jerusalem Post.

The donation deed from Abramovich and other documents are part of a trove linked to a Cypriot offshore financial services company, MeritServus, that did extensive business with Abramovich. The records were obtained by the nonprofit group Distributed Denial of Secrets and shared with news organizations, including ICIJ and The Washington Post. The MeritServus documents dovetail with Israeli property records that show that Yuditskaya-Berliner finished buying the apartment on the day that the money from Gemini flowed into her Tel Aviv bank account.

The transaction itself is unremarkable, dating back nearly 18 years and involving a sum so small that it would barely register as a rounding error in the multibillion-dollar offshore ledgers of Russian oligarchs. The leaked transaction records reporters obtained do not include any mention of Putin or Rabbi Boroda instructing Abramovich to pay Yuditskaya-Berliner.

To date, the documents provide the clearest evidence of an instance in which Abramovich used a portion of his wealth, however modest, to carry out a transaction benefiting the Russian president’s personal sphere. Western intelligence agencies and Russia experts have long believed that Abramovich – and other oligarchs – function as “wallets” for the Russian president, but the evidence has never been so compelling.

Deep ties everywhere

An orphan who climbed his way into Russia’s oil trading sector, Abramovich is said to have gotten a hardscrabble start in business, selling plastic ducks out of a Moscow apartment before moving into hog farming. By the mid-1990s Abramovich had vaulted into elite ranks of Russia’s oil sector under the presidency of Boris Yeltsin.

After meeting Putin in 1999, Abramovich became an ally of the upward-bound Russian leader.

Abramovich’s wealth grew rapidly as Putin consolidated power over the oil-rich nation. Abramovich received a major windfall in 2005 when Putin’s government agreed to pay $13 billion to reacquire Sibneft, which Abramovich and a partner had bought a decade earlier for around $200 million, according to the New York Times.

Abramovich has since spent much of his time and wealth pursuing a luxurious life outside Russia. He has invested vast sums in U.S. hedge funds and owns one of the world’s largest yachts, along with properties in England, France and Colorado.

A member of a Jewish family, Abramovich has also established deep ties to Israel, donating millions of dollars to conservative Jewish organizations. In 2018, he obtained Israeli citizenship.

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine last year, however, Abramovich has been scrambling to protect his vast business interests from Western sanctions. Citing his “close” ties to Putin, the European Union and the United Kingdom moved to freeze his assets and bar entry by his yachts or private planes. In perhaps the biggest blow of all, he was forced to sell the Chelsea Football Club in a deal approved by the British government that was designed to prevent him from pocketing the profits.

Last year, Abramovich became a conduit for peace talks and cease-fire negotiations between Russia and Ukraine. Despite having little known effect on the conflict, he won a respite from U.S. sanctions because Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky believed Abramovich to be a potentially useful channel to Putin.

Yuditskaya-Berliner, who was born in Ukraine, had little to say about Putin’s early efforts to dismember that country. In her 2014 interview, she was asked about Russia’s proxy war in eastern Ukraine and Putin’s annexation of Crimea. She demurred, saying that she was “not into politics.”

Yuditskaya-Berliner died in 2017 at the age of 96, and efforts to locate surviving relatives were unsuccessful as this story went to press. When a reporter visited the apartment last month, no one answered the knock on the door. It’s not clear what, if anything, goes on there these days. But according to Israeli records, Yuditskaya-Berliner’s will left instructions for the apartment: Give it to the Russian Federation.