Cholera and the age of the water barons

The explosive growth of three private water utility companies in the last 10 years raises fears that mankind may be losing control of its most vital resource to a handful of monopolistic corporations.

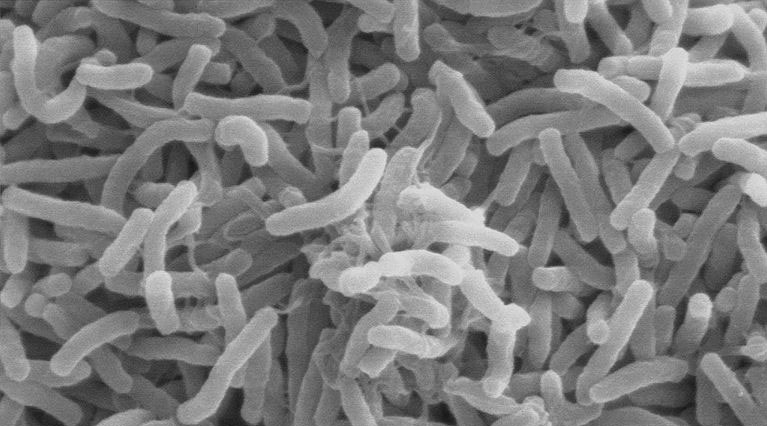

When cholera appeared on South Africa’s Dolphin Coast in August 2000, officials first assumed it was just another of the sporadic outbreaks that have long stricken the country’s eastern seaboard. But as the epidemic spread, it turned out to be a chronicle of death foretold by blind ideology.

In 1998, local councils had begun taking steps to commercialize their waterworks by forcing residents to pay the full cost of drinking water. But many of the millions of people living in the tin-roof slums of the region couldn’t afford the rates. Cut off at the tap, they were forced to find water in streams, ponds and lakes polluted with manure and human waste. By January 2002, when the worst cholera epidemic in South Africa’s history ended, it had infected more than 250,000 people and killed almost 300, spreading as far as Johannesburg, 300 miles away.

Making people pay the full cost of their water “was the direct cause of the cholera epidemic,” David Hemson, a social scientist sent by the government to investigate the outbreak, said in an interview. “There is no doubt about that.”

The seeds of the epidemic had been sown long before South Africa decided to take its deadly road to privatization. They were largely planted by an aggressive group of utility companies, primarily European, that are attempting to privatize the world’s drinking water with the help of the World Bank and other international financial institutions.

The days of a free glass of water are over, in the view of these companies, which have a public relations campaign to accompany their sales pitch. On a global scale, and in many developing nations, water is a scarce and valuable and clearly marketable commodity. “People who don’t pay don’t treat water as a very precious resource,” one executive said. “Of course, it is.”

A yearlong investigation by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), a project of the Center for Public Integrity, showed that world’s three largest water companies — France’s Suez and Vivendi Environnement, and British-based Thames Water, owned by Germany’s RWE AG— have since 1990 expanded into every region of the world. Three other companies, Saur of France, and United Utilities of England working in conjunction with Bechtel of the United States, have also successfully secured major international drinking water contracts. But their size pales in comparison to that of the big three.

The investigation shows that these companies have often worked closely with the World Bank, lobbying governments and international trade and standards organizations for changes in legislation and trade agreements to force the privatization of public waterworks.

While private companies still run only about 5 percent of the world’s waterworks, their growth over the last 12 years has been enormous. In 1990, about 51 million people got their water from private companies, according to water analysts. That figure is now more than 300 million. The ICIJ investigation, which tracked the operations of the six most globally active water companies over a 12-year period, showed that by 2002, they ran drinking water distribution networks in at least 56 countries and two territories. In 1990, they had been active in only about a dozen countries.

Revenue growth, according to corporate annual reports reviewed by ICIJ, has tracked with the companies’ overseas expansion. Vivendi Universal, the parent of Vivendi Environnement, reported earning over $5 billion in water-related revenue in 1990; by 2002 that had increased to over $12 billion. RWE, which moved into the world water market with its acquisition of Britain’s Thames Water, increased its water revenue a whopping 9,786 percent – from $25 million in 1990 to $2.5 billion in fiscal 2002.

This explosive growth rate has raised concerns that a handful of private companies could soon control a large chunk of the world’s most vital resource. While the companies portray the expansion of private water as the natural response to a growing water shortage crisis, thoughtful observers point out the self-serving pitfalls of this approach.

“We must be extremely careful not to impose market forces on water because there are many more decisions that go into managing water — there are environmental decisions, social-culture decisions,” said David Boys of the U.K.-based Public Services International. “If you commodify water and bring in market forces which will control it, and sideline any other concern other than profit, you are going to lose the ability to control it.”

So far, privatization has been concentrated in poorer countries where the World Bank has used its financial leverage to force governments to privatize their water utilities in exchange for loans.

In Africa, the ICIJ examination of water company records showed that they have expanded into at least 10 countries from three in 1990; they are also active in at least 10 Asian countries and eight Latin American ones, three in North America, two in the Caribbean plus Puerto Rico, three in the Middle East plus the Gaza Strip, Australia/New Zealand and in 18 European nations, with most of the expansion in Eastern Europe. There, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development has played a key role in encouraging countries to privatize in exchange for loans.

Having firmly established themselves in Europe, Africa, Latin America and Asia, the water companies are expanding into the far more lucrative market of the United States. In recent years, the three large European companies have gone on a buying spree of America’s largest private water utility companies, including USFilter and American Water Works Co. Inc. Peter Spillett, a senior executive with RWE’s water unit Thames, told ICIJ his company projects that within 10 years it will double its market to 150 million customers primarily because of expansion into the United States. So far, the Europeans have privatized waterworks in several mid-sized U.S. cities, including Indianapolis and Camden, N.J., and are trying to secure contracts in New Orleans. Their expansion, however, recently ran aground in Atlanta, where the city canceled its 20-year contract — the largest of its kind in the United States — with a Suez subsidiary after only four years and returned control to the public utility.

The water companies have also dramatically increased their lobbying and federal election campaign spending. In Washington, they have already secured beneficial tax law changes and are now trying to persuade Congress to pass laws that would force cash-strapped municipal governments to consider privatization of their waterworks in exchange for federal grants and loans. Government and industry studies have estimated that U.S. cities will need between $150 billion and $1 trillion over the next three decades to upgrade their aging waterworks.

Worldwide, the ICIJ investigation showed that the enormous expansion of these companies could not have been possible without the World Bank and other international financial institutions, such as the International Monetary Fund, the Inter-American Development Bank, the Asian Development and the European Bank for Reconstruction. In countries such as South Africa, Argentina, Philippines and Indonesia, the World Bank has been advising the leaders to “commercialize” their utilities as part of an overall bank policy of privatization and free-market economics.

In South Africa, heavy lobbying by private multinational water companies, such as Suez, together with advice from the World Bank helped persuade local councils to privatize their waterworks. Some communities began turning their utilities into commercial enterprises as a preparatory step to outright privatization. Others immediately contracted out to private water. Urged by the World Bank to introduce a “credible threat of cutting service,” the local councils began cutting off people who couldn’t pay. An estimated 10 million people have had their water cut off for various periods of time since 1998. The result has been cholera and other gastrointestinal outbreaks.

The ICIJ investigation focused on the activities of these companies in South Africa, Australia, Colombia, Asia, Europe, the United States and Canada.

The investigation showed that while these companies claim to be “passionate, caring and reliable,” as one company states, they can be ruthless players who constantly push for higher rate increases, frequently fail to meet their commitments and abandon a waterworks if they are not making enough money. As in South Africa, the water companies are pillars of a user-pay policy that imposes high rates with little concern over people’s ability to pay. These rates are then enforced by water cutoffs despite the serious dangers to people’s health that these actions create.

The water companies are chasing a business with potential annual revenue estimated at anywhere from $400 billion to $3 trillion, depending on how you do the math. Water is the basis of life and, if they have to, people will pay just about anything to get it.

“These companies want to crack open this oyster and go get the pearl inside. It’s big money,” said Boys of Public Services International.

About 1.5 billion people do not have access to safe drinking water. The United Nations predicts that by 2025 two thirds of the world’s population will experience shortages of clean water. Experts claim enormous financial resources will have to be expended to meet this need.

Water companies, seeing profit in the crisis, are using current fears over the scarcity of clean water to advance their financial interests, says Riccardo Petrella, professor at the Catholic University of Louvain in Belgium and an advisor to the European Union on Science and Technology.

“Water has become important for capital because water is increasingly characterized by a crisis of scarcity,” he told ICIJ. “And scarcity is the basis of modern capitalism.”

“They enter into the water sector in the developing countries because they start from the principle that even the poor are ready to pay for water,” he said. “They say ‘water for free is not possible – even the poor understand this.”

Financial fund managers are taking note of the expanding water market. Switzerland’s second oldest bank, the Pictet Bank, last year started its Global Water Fund in the United States after starting a similar one in Europe two years earlier. They offer a basket of water companies and predict that by 2015 75 percent of European and 65 percent of U.S. water utilities will be privatized.

As Thames’ executive Peter Spillett said: “You have such a steady market, there is huge growth potential.”

He noted that “water stocks actually do better than other utilities” because of the long-term contracts that stretch for 10 to 30 years, offering a reliable and predictable return on investment. “That is why a lot of pension funds as well as private individuals are willing to put money into it,” he said.

Suez told ICIJ it instructs all its companies to be profitable within three years, and the rate of return has to be at least 3 percent over the cost of capital.

But the private companies are increasingly running up against strong opposition because of the vital nature of water itself and the politics that swirl around it. The most famous example of this is the privatization in Cochabamba, Bolivia. After Aguas del Tunari, a consortium jointly owned by Bechtel and United Utilities, took control of the city’s waterworks in 1999 without any contract bidding, the company announced water rate increases of up to 150 percent. Manager Geoffrey Thorpe threatened to cut off people’s water if they didn’t pay.

The contract gave the company control over ground water and allowed it to close down people’s private wells unless they paid Aguas del Tunari for the water. Union leader Oscar Olivera said: “They wanted to privatize the rain.” When protests erupted throughout the city of 450,000 in 2000, police and army troops were called in. They killed two people. The government reacted by canceling the concession. Aguas del Tunari is suing the Bolivian government claiming losses of a reported $25 million, although Bechtel has stated that it has not put a number on its claim. The suit is before the International Center for the Settlement of Investment Disputes, an organization of the World Bank Group.

It was on the advice of the World Bank that Bolivia began privatizing its water services in the mid 1990s. Discussions about Cochabamba’s water began in 1995, Christopher Neal, the World Bank’s external affairs officer for Latin America, told ICIJ. “The Bolivian government agreed, as a matter of policy, with the Bank’s view that [privatization] was needed there,” Neal said. However, according to Menahem Libhaber, the bank’s lead water engineer for Latin America, the bank opposed the Cochabamba deal with Aguas del Tunari because it believed it was not financially viable.

In an interview with ICIJ, Bechtel spokesman Jeff Berger blamed the Bolivian government for the Cochabamba debacle. He claimed the government failed to explain the long-term benefits of privatization to the people by delivering flyers and taking out ads in newspapers.

The free marketers

Although Neal told ICIJ the “bank is not ideological” about privatization, the investigation showed that privatization is a hallmark of many of its loan projects.

Lending about $20 billion to water supply projects over the last 12 years, the World Bank has not only been a principal financer of privatization, it also has also increasingly made its loans conditional on local governments privatizing their waterworks. The ICIJ study of 276 World Bank water supply loans from 1990 to 2002 showed that 30 percent required privatization — the majority in the last five years.

In major water privatizations around the world — such as Buenos Aires, Manila and Jakarta – the ICIJ investigation showed that the World Bank flexed its financial muscle to persuade governments to tender long-term waterworks concessions to the major private companies.

The investigation also showed that the bank advised the countries how to privatize their waterworks and often helped finance the privatization process. In the case of Buenos Aires, the World Bank not only helped finance the privatization but also took, through one of its branches, a 7 percent stake in the new company, Aguas Argentinas, which is controlled by Suez. The World Bank loaned one of its own senior managers to negotiate large water rate increases with the Argentine government. The manager then headed a World Bank team that gave a $30 million loan to Argentina. This occurred at the same time that Aguas Argentinas and its shareholders were making huge profits of as much as 25 percent. One shareholder, an important Argentine businessman, earned a profit of $100 million on the privatization.

In Jakarta, Indonesia, the ICIJ investigation showed that World Bank officials not only encouraged privatization of the city’s utility but also stood by as two multinationals secretly negotiated with the Suharto regime for the transfer of the public waterworks into their control. The two companies, Suez and Thames, entered into partnerships with a business crony and a son of the former dictator Suharto to gain control over the city’s waterworks. Both men then made significant profits on the deal.

The bank claims its policy of privatization alleviates poverty by bringing management efficiency and private capital to developing countries whose cash-starved water utilities are usually in a mess. The bank argues that private companies succeed in bypassing the usual bureaucratic morass and political cronyism and corruption that corrodes so many public utilities in poorer countries. While it is clear that considerable improvements have been brought to many waterworks as a result of privatization, in many cases, the companies put in relatively little capital of their own, relying primarily on loans from the World Bank and related international financial institutions to help cover costs of repairing and expanding waterworks networks.

There’s also evidence that if the World Bank applied the same energy and money to improving local utilities, while allowing them to maintain control of their water systems, the local utility would actually perform better than private companies.

In Manila, Maynilad Water, of which Suez controls 40 percent, announced in December 2002 it was pulling out of its 25-year contract, abandoning a waterworks serving an area of 6.5 million people. The company was unable to raise capital to meet contract demands and, as an independent study commissioned by the local regulator indicates, contracted work to affiliate companies. Maynilad is before an arbitration court seeking $337 million from the Philippines government as reimbursement for what it claims is invested capital. The government argues, however, the company is owed only a fraction of that amount. The company is also transferring to the government debts totaling $530 million.

A global oligarchy

The investigation also showed that the water companies have joined forces with the World Bank and the United Nations to create an array of international think tanks, advisory commissions and forums that have dominated the water debate and established privatization as the dominant solution to the world’s water problems.

“What we have seen during the 1990s has been the setting-up of a kind of global high command for water,” Riccardo Petrella, a leading researcher on the politics of water, wrote in the French daily Le Monde in 2000.

The leading think tank on water issues and the principal adviser to the World Bank and United Nations is the World Water Council, which was established in 1996 by the World Bank and the United Nations. It is headquartered in Marseille, France, and one of its three founding members is René Coulomb, a former Suez vice-president.

In 1998, the WWC created the World Water Commission to promote public awareness of water issues and to help formulate global water policies. The commission holds water conferences around the world and channels its policy statements through international forums held every three years.

Men with strong privatization backgrounds run the commission. These include former Suez CEO Jérôme Monod, Enrique Iglesias, president of the Inter-American Development Bank and Mohamed T. El-Ashry, CEO of the World Bank/U.N. Global Environment Facility. Commission chairman is World Bank Vice President Ismail Serageldin.

Both of these institutions strongly support privatization and a user-pay policy. “Global experience shows that money is the medium of accountability,” the commission said in a 2000 report.

The commission has held two international forums on water with a third planned for Kyoto, Japan, in March 2003. At its forum at The Hague in March 2000, the commission issued a policy statement that said water management was the main problem facing mankind and the solution was to treat water like any other commodity and open its management to free market competition.

Serageldin stated that water delivery should be in private hands, but publicly regulated, in the same way as private companies run the food industry.

The ties that bind the World Bank to the major water companies include shared membership on the boards of various policy institutions as well as personal and business relations.

Monod was special counselor to the International Monetary Fund’s director, Michel Camdessus, when Monod was Suez’s CEO. After Camdessus retired in 2000, he was named chair of the “International Panel for New Investments in Water,” an initiative organized by the water companies. The panel’s directors include William Alexander, group chief executive of RWE’s Thames Water of London, and Suez Vice President Gerard Payen.

At its first meeting in Paris in February 2002, the panel focused on “how to increase the rate of return on water projects, and the related difficulty of implementing the full cost recovery pricing of water.”

Another panel member is the Global Water Partnership (GWP). The chairwoman of its steering committee is Margaret Catley-Carlson, a former Canadian deputy health minister. She is also chairwoman of the Suez Water Resources Advisory Committee. The GWP is a partnership of government, corporate and professional organizations examining water issues. It claims: “The water crisis is a governance crisis, characterized by a failure to value water properly and by a lack of transparency and accountability in the management of water. Reform of the water sector, where water tariffs and prices play essential parts, is expected to make stakeholders recognize the true cost of water and to act thereafter.”

On another front, water companies are working closely with the European Union to enforce trade barriers against any country that refuses to open its water utilities to privatization.

Working with the EU trade officials, the water companies are also trying to persuade the World Trade Organization to force countries to open their utilities to free market forces. Documents obtained by ICIJ show that the European Commission trade office works closely with Thames, Suez, Vivendi and other private water companies to push for a reduction in trade barriers with the WTO.

In a May 2002 letter, EU trade commissioner Ulrike Hauer wrote to Thames, Suez and Vivendi, thanking them for their contribution toward negotiations to reduce trade barriers in “water and waste water services” with a view to open these markets to European companies.

On a third front, the French government recently made a proposal to the quasi-governmental International Organization for Standards (ISO), a regulatory branch of the WTO, to set international standards for water utilities. Effectively, the committee would develop rules on how to manage all aspects of water service and delivery. Critics believe this will help the WTO forge trade rules that would force countries to open their public utilities to privatization.

“The companies have a clear strategy based on three things: the WTO, the WIPO (World Intellectual Property Org) and the ISO,” Petrella told ICIJ. “Through trade, intellectual property and standardization they are going to conquer the water world.”

Financial titans, bribery and fraud

In addition to their political connections, each of the three leading companies has enormous financial resources. Each is among the top 100 corporations in the world. Together they had revenue in 2001 of $156.7 billion and continue to grow at a rate of about 10 percent a year, outpacing the economies of some of the countries in which they operate. The gross domestic product of Bolivia, for example, is $21.4 billion.

The companies also have more employees than most governments. Vivendi Environnement, alone, employs 295,000 worldwide; Suez employs 173,000.

Both Suez and Vivendi have doubled their customer base in the last 10 years with Suez serving 125 million water customers and Vivendi 110 million. RWE’s Thames Water is a distant third with 51 million but its recent acquisition of American Water Works Co. Inc. will increase it to 70 million.

In France, both Suez and Vivendi have close political ties with the national and local governments. Executives of the two companies have been charged and, in some cases, convicted of illegal campaign contributions to politicians and of using bribery and fraud to obtain water and other municipal contracts. In one case, witness testimony implicated former Suez CEO Monod, who is now chief adviser to French President Jacques Chirac. Monod has never been charged and has denied any wrongdoing.

Though competitors, the companies often form joint ventures to obtain water concessions in foreign countries. The ICIJ investigation, for example, revealed that Thames and Vivendi formed a business alliance in 1995 to capture the Asian market. Suez and Vivendi share interest in Buenos Aires. And Thames and Suez, with the support of the former Indonesian dictatorship, divided up Jakarta.

Finally, the private water companies make promises they often can’t keep – a tactic one World Bank water official called “over selling.” Essentially, they promise to deliver a better service at a lower price. The ICIJ investigation found, however, that governments often drive up water prices just prior to privatization to give water companies room to immediately reduce prices and win popular approval. Once a company has won the contract and lowered prices, it often quickly attempts to renegotiate for higher rates and reduced performance targets. The fact that the companies now control the city’s waterworks gives the company tremendous leverage in these negotiations. In many cases, water prices soar and original targets for expanded water and sanitation systems are not met.

In Buenos Aires, for instance, Suez-controlled Aguas Argentinas almost immediately put pressure on the government to renegotiate the concession contract for more favorable terms.

Thames Water executive Peter Spillett complained to ICIJ that his company has lost contracts because of this tactic. “What we find a bit hard is that in many cases our competitors seem to go in much lower, and then within a year or two of having successfully gotten that contract, they seek to re-negotiate with the government of the city.”

Since the companies prefer to be paid in American dollars, falling local currencies usually lead to demands for rate increases. Despite earning substantial profits, Aguas Argentinas recently canceled expansion plans and threatened to curtail services unless the government agreed to higher rates to compensate for foreign exchange losses.

The companies claim privatization is good because it brings the latest ideas and technology to tired public utilities and clarifies the responsibilities and mission of the water utility.

“In many cases, when only public servants are involved with delivering water services or sanitation services, the goals which are expected by the political decision-makers are not visible, they are not explained,” Suez Vice President Gérard Payen told ICIJ. “When you involve the private sector, the community has more information and the situation is more transparent.”

But the ICIJ investigation showed that companies frequently insist that all or part of their contracts remain secret. Regulatory authorities in Buenos Aires, Manila and Jakarta told ICIJ they often feel powerless in the face of demands from the water companies because they don’t have access to company figures.

When companies are fined for not achieving performance targets, they often don’t pay, preferring to appeal rulings in lengthy and expensive arbitration and court proceedings.

Even in developed countries, such as Australia and Canada, which generally have stronger regulatory bodies than poorer countries, privatization has weakened public accountability. In Sydney and Adelaide, Australia, major sewage treatment and water quality problems were kept secret from the public as regulatory authorities and the private companies argued over responsibility. In Hamilton, Ontario, a private company took several years before it agreed to settle fines after millions of gallons of sewage spilled into the streets and flooded basements.

Nor is there any assurance that the private companies are financially reliable. Since 1998, when Hamilton privatized its utility, the city has had five different operators. Two of the companies, one of which was Enron Corp., collapsed under the weight of fraud scandals. In a period of just five years, the concession has been owned by the city government, one local company, two American companies and was recently taken over by the German utility RWE.

“You don’t know who you are dealing with,” said Hamilton city councilor Sam Merulla. “When you deal with the private sector on behalf of the public sector, you need stability. In Hamilton, it has been a revolving door of international corporate owners dealing with one of the most precious things we have – water.”

Global expansionists

Having established firm footholds on six continents, the big three water companies say they now intend to concentrate most of their efforts on the potentially lucrative markets of North America, China and Eastern Europe. All three told ICIJ they hope to more than double their revenue and their client base in the next 10 years.

Thames’ Spillett said China is opening up because the World Bank is ready to spend money there, which makes it more attractive to private companies.

“China is a bit of a sleeping giant because for people at the World Bank there has always been a bit of difficulty regarding financing issues. They tend to have gotten a bit clearer just recently.”

Some countries are definitely not on the privatization agenda any more. Yves Picard, managing director of Vivendi in South Africa, said his company is not interested in concessions in southern Africa unless the World Bank or other institutions finance the capital costs. Otherwise, he said, there is no payback for the company because people are too poor to pay the high water rates private companies charge to cover their capital costs.

Dependence on the World Bank appears to be increasing. There is rising concern among the companies that capital markets are not open to them because water is such a volatile political issue and many poorer countries have unstable local currencies.

In a presentation on private sector involvement in the water business before the World Bank in February 2002, J.F.Talbot, chairman and CEO of France’s third-largest water company, Saur, warned that without increased financing from institutions like the World Bank major international water companies will “stay at home.”

Much of their expansion plans depend on whether people ultimately accept the idea of water as a commodity. In other words, the days of the free glass of water are gone. Everyone must pay for water is the principal message sent out by the World Water Council and its affiliate organizations. The fact that people are increasingly accustomed to buying bottled water can only be encouraging for the big water utilities.

Yet, concerned about the backlash from privatizations such as Cochabamba’s, the companies are beginning to couch their words in less mercantile terminology. After all, what makes water different is that, like air, it’s irreplaceable. There are no choices allowing customers to reject one for another. How can anyone market something that is both vital to life and has no alternative? As the cholera victims of South Africa know only too well, nothing can replace clean water.

“Everybody who thought water was a commodity lost,” Vivendi’s President Olivier Barbaroux told ICIJ. “We do not sell water. You take the water and you give it back. Exactly the same amount. What we are doing is bringing the water to your home, making it clean for you to use, and then taking it back and putting it back in nature clean. And that is the service we are bringing.”

Suez’s Payen flatly stated: “Water is not a commodity. It is a public good. It is also a social good. It is essential for life.” So what does Suez sell? “We provide the essentials of life.”

Thames, however, is sticking to the commodity message. “Water is both a commodity and a [public] service,” Spillett said. He then compared the water business to a brewing company.

“Clearly people do not understand the value of water and they expect it to fall from the sky and not cost anything. But if we use an analogy with beer – that’s 99 percent water – but breweries have added their hops and malt, and it has gone through a lot of processing and the end product has a lot of added value and people are prepared to pay a lot of money for it. In a sense purifying water from the raw state, then treating it and bringing it to people and taking it away again is almost the same industrial product. You have a lot of value-added there and people, if they don’t realize it’s got a value and don’t pay for it, don’t treat it as a very precious resource. Of course, it is.”

The companies also claim that they are not really privatizing water, but rather managing utilities under in partnership with governments. They call these “Public Private Partnerships” or PPPs.

For critics of privatization, however, the essential issue is not water itself, but access to water. And the key to access is control – who has their hands on the tap.